Source: anja_johnson

Source: anja_johnson

“All men are rapists,” I read on the back cover of Susan Brownmiller’s Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape in the student bookstore. Determined to impress women with my intellectual and feminist prowess by debunking that quote, I bought the book and doggedly read all 480 pages trying to find it. Twice.

Yes, I was rather naive about the whole dating game. Even worse, you can imagine how I felt years later, when I learned that she never actually said that. Rather, it was a big misinterpretation of her statement that rape “is nothing more or less than a conscious process of intimidation, by which all men keep all women in a state of fear” (p. 5), albeit an understandable one. Indeed, it’s probably what she’s become best known for, an enduring catch-phrase of pop-feminism that publishers would knowingly exploit to sell the book to me 2 decades later.

Which is a shame, because along with Menachem Amir, she was instrumental in overturning long-held conventions that rape was simply a spontaneous act of lust, instead demonstrating that it is more “a deliberate, hostile, violent act of degradation and possession on the part of a would-be conqueror, designed to intimidate and inspire fear…” (p. 439). Or in short, it’s due to her that surely all reading this are aware that sexual violence is all about power, and not surprised to hear this reaffirmed by the survey “Sexual Violence Among Men in the Military in South Korea” by Insook Kwon et. al., Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Vol. 22, No. 8, 1024-1042 (2007), the subject of today’s post.

The first comprehensive survey of its kind, in English or Korean, it was prompted by the suicide of a Korean soldier in July 2003, which received tremendous attention in the media because sexual violence by his superiors seemed to have played a role; after all, with 250,000 men forcibly conscripted each year, any implication that it wasn’t an isolated incident meant that there were far more victims. And in point of fact, with the proviso that the authors’ (undefined) notion of “sexual violence” appears to be much broader than a layperson’s as I’ll explain, they did indeed find that 15.8% of respondents experienced it during their time in the military, either as perpetrators or victims.

The first comprehensive survey of its kind, in English or Korean, it was prompted by the suicide of a Korean soldier in July 2003, which received tremendous attention in the media because sexual violence by his superiors seemed to have played a role; after all, with 250,000 men forcibly conscripted each year, any implication that it wasn’t an isolated incident meant that there were far more victims. And in point of fact, with the proviso that the authors’ (undefined) notion of “sexual violence” appears to be much broader than a layperson’s as I’ll explain, they did indeed find that 15.8% of respondents experienced it during their time in the military, either as perpetrators or victims.

But before discussing the implications of that however, and especially what it says about the role of the military in the socialization of Korean men, let first provide an overview of the survey so you can make your minds (with a nod to copyright, I won’t upload the survey itself here sorry, but please feel free to email me if you’d like your own copy). And so, without any further ado:

The survey was conducted from November 2003 to February 2004, with researchers meeting 2 groups: 362 postconscripts, then students, at 6 different colleges; and 409 current conscripts, 115 at bus and train stations while they were on leave, and 294 in visits to their barracks with the official cooperation of the Ministry of Defense. From each group, there were 266, 111, and 294 valid samples respectively, giving a total of 671 valid samples out of 771 soldiers surveyed (the bulk excluded being postconscripts, and because more than 3 years had passed since their military service). They also conducted in-depth interviews of 8 perpetrators in army prison, and 3 victims.

Highlights of the results include (all emphases mine):

Of 671 valid respondents who participated in this survey of victimization, perpetration, and observation, a total of 103 people (15.4%) answered that they were directly victimized, 48 people (7.2%) answered that they had direct experience as perpetrators, and 166 people (24.7%) answered that they witnessed sexual violence in the military.

Excluding eyewitnesses, a total of 106 soldiers (15.8%) directly experienced physical sexual violence, either as perpetrators or victims in the military. A very high number of soldiers also indicated they experienced sexual violence as perpetrators and as victims: 59 soldiers (55.7%) were victims only, 39 soldiers (36.8%) were victims and perpetrators, and only 8 soldiers (7.5%) were exclusively perpetrators. Among perpetrators, 83% had experienced sexual violence in the military when they had been lower ranked soldiers. This feature of high number of perpetrators having previously experienced victimization themselves could be seen as the most unique feature of sexual violence among men in the military. (p. 1028)

(Source: anja_johnson)

(Source: anja_johnson)

And:

Victims named higher ranking soldiers (71.1%), junior officers (7%), and officers (3.1%) as their perpetrators, totaling 81.2% of victims who responded that someone of a higher rank forcibly imposed sexual contact….

Also, the eight perpetrators and three victims who agreed to be interviewed, as well as six cases recorded by the Korean Sexual Violence Relief Center and reports by military judiciary officers, confirmed that victims of sexual abuse were in lower ranks than their perpetrators. All victims had been victimized by higher ranking soldiers, and eyewitnesses reported likewise. In sum, sexual violence among men in the military in South Korea was committed primarily by a higher ranking solider against a lower ranking soldier. (p. 1029)

The types of abuse, as reported by victims and witnesses (p. 1031; multiple answers permitted):

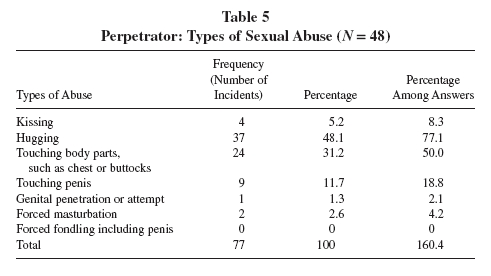

As reported by the perpetrators (p. 1033):

Also note that 22.1% of victims (but only 7% of perpetrators) reported that physical violence accompanied the sexual violence, and that 71.8% of victims and 90.7% of perpetrators responded that the acts of sexual violence when others were watching (I’ll return to the latter point shortly). And in particular, eyewitnesses reported that 22.5% of the sexual violence they saw involved touching genitals, and 5.1% involving anal penetration (or the attempt), nearly 2 and 5 times higher than victims reported respectively.

Reflecting on the discrepancies, Kwon et al. found that:

…people tended to feel more comfortable talking about what might be considered part of a general sexual culture—such as kissing, hugging, and telling sexually explicit jokes—but answers were less forthcoming when concerning sexual violence of a more serious degree. (p. 1032)

Which for a long time I simply didn’t understand: how on Earth was that the “general sexual culture” of the military? Well, first consider that:

When asked, “In the military, have you ever been forced to talk about sexual experiences, even when you did not want to?” almost one third (32.7%) of the 667 respondents answered affirmatively. To the question, “Have you ever experienced negative consequences either because you did not have any sexual experiences or because you refused to discuss your sexual experiences?” a total of 218 soldiers (32.7%) answered that they had been forced to talk about sexual experience. (p. 1028)

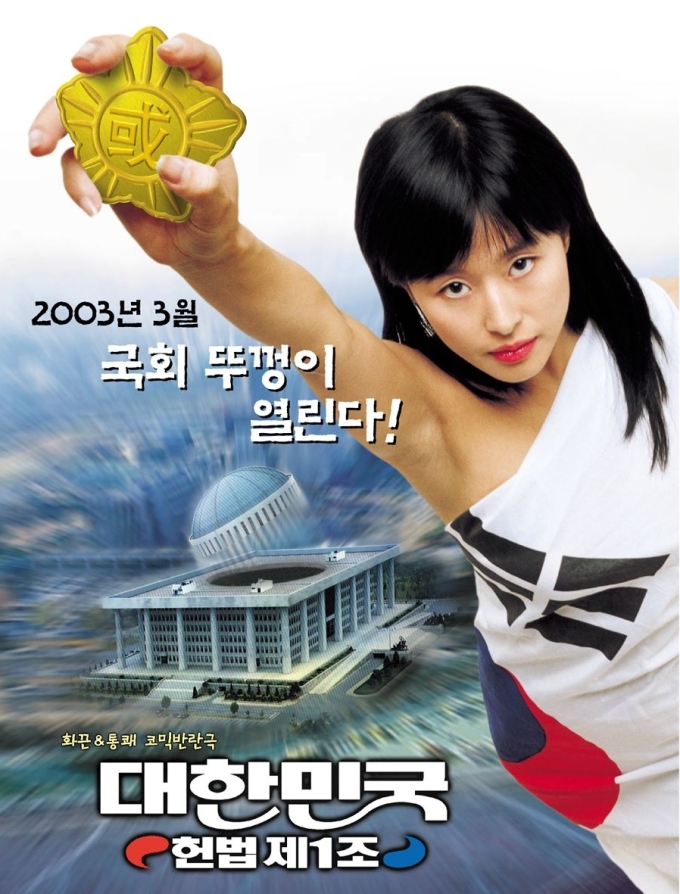

And that this mandatory disclosure of sexual experience has long been regarded as “an essential part of sexual culture in the military” is corroborated by numerous references in Korean movies to the practice of virgins visiting a prostitute before starting one’s military service, of which I highly recommend the satirical comedy The First Amendment of Korea below.

(Source)

(Source)

Next, there is the fact that victims of sexual violence tended to interpret it as:

…intimacy or playfulness, because identification as a victim of sexual violence would imply one’s fragility and vulnerability. This tendency to minimize and trivialize injury was clear in cases where abuse continued for a long time, and in situations where a clear power dynamic between the perpetrator and the victim made resistance much more difficult for the victim. (p. 1033)

Moreover, perpetrators:

…did not force sexual contact on their peers with whom they had even closer relationships [than inferiors]. The intimacy in question was strictly an intimacy from the position of the higher ranking soldier.

Kwon et al. further discuss the natural difficulties victims had in refusing advances by a superior, and crucially, why the third most common form of sexual violence was touching a victim’s genitals. But why, particularly when only 5.4% of victims thought that their perpetrators were genuinely homosexual? Well, as one victim noted:

…unlike in the general society where one could not treat another person with complete disregard for age, educational level, or class, in the military, higher ranking soldiers could treat lower ranking soldiers as one pleased—including touching their genitals. (p. 1035)

And after a discussion of the right to control and abuse the body being a very useful method for militaries to reaffirm its hierarchical order, and of the role of the penis as a symbol of power and authority throughout history, they note that, hence:

…teasing or forceful contact with one’s penis becomes a way to prove the victim’s lack of power.

(Source: Journey to Perplexity)

(Source: Journey to Perplexity)

Needless to say, the effects of this are amplified if done in public settings, and indeed 90.7% of perpetrators responded that people were watching when their sexual violence occurred, with the vast majority of witnesses either actively engaging in it in some way (23.7%), passively consenting by simply watching (57.9%), or pretending not to see (10.5%) rather than attempting to stop it: hence a “general sexual culture.”

But continuing with why:

…violence feminizes victims of sexual violence in two ways. The victim is reduced to a sexual object, like many women typically face in society, and as the powerless victim of violence, he is further feminized. Men who are victimized by sexual violence, then, become someone whose masculinity is lacking or damaged. Hierarchical order reasserts itself amid all this, and men collectively try to be on the offensive to affirm their aggressive masculinity. (pp. 1035-36)

And finally, the testimony of a perpetrator himself on why he did it, who said that he used sexual violence in lieu of physical violence sometimes, forcing sexual contact by “not hitting every time, and not joking around but harassing them”:

[Like harassing them…] Yes, I can’t hit them every time . . . and it’s not just joking around, but harassing them. . . . For instance, making them clean things repeatedly. Stuff like that. . . . If they were from wealthy families . . . or had a lot of education themselves . . . the superiors are ahead only because they came to the military before them . . . honestly . . . when you don’t have much to show for, and if they kiss ass to superiors who intimidate them . . . and if they think you’re not all that . . . well, you can’t beat them and so I kept thinking about ways to give them hell in the military, legal ways . . . and that’s how I ended up. (pp. 1036-37)

({2-365} Tick Tock by Dee’lite)

({2-365} Tick Tock by Dee’lite)

But what to make of all this?

At this point, it seems appropriate to point out my own complete lack of experience with the Korean military, as well as not even having any close relationships with any Korean men from whom I could learn about their military service, and so I would be very grateful to hear from those that have either. But then my own inexperience is essentially irrelevant here, as I’m largely passing on the results of renowned experts in the field (scroll down to note #32 here for more information on Kwon for instance); moreover, my own interest in on what is implied for Korean culture and sexuality as a whole, and so let me pass on the following description of military life provided by Ask a Korean, in his own excellent series on military service in Korea:

For some of today’s Korean young men, who have gone soft since the days of their fathers, military experience can be unbearable. Physical exercise is grueling, the superiors can be arbitrary and insulting, and your squad mates could shun you if you are responsible for putting the whole squad in trouble. Given that these guys, just like any other soldiers in Korea, can access guns and grenades, it should be no surprise that recently there has been a string of incidents in which a draftee shoots up his squad or toss a grenade in the squad room, killing many….

….[But there are definitely good life lessons to be learned from the experience, although it may be debatable whether learning those lessons is a good use of 2 to 3 years of young men in their prime. To put it bluntly, the military experience builds Korean men’s tolerance for all the life’s bullshit. As the Korean described so far, there is no shortage of bullshit – some of them perhaps the worst to be encountered in life – in the military. Exhausting physical training, insults and condescension from the superiors, and wasting time on arbitrary and trivial errands are all part of the experience. For young Korean men in the military, there is no choice but to simply grin and bear them. Once they finish bearing it, they know that most difficulties in life would be easier than what they already went through. The combination of such tolerance and insight, some may call it maturity – because, as anyone who has had a regular job can tell you, life as an adult has a lot of crap that we must simply grin and bear.

(Band of Brothers by The U.S. Army Photostream)

(Band of Brothers by The U.S. Army Photostream)

And in the next post in that series (my emphasis):

…one can argue that the military culture neatly coincides with traditional Korean culture – in both cultures, seniority automatically commands respect and loyalty. It is not surprising, then, that Korean workplaces are often run just like a squad in the military. You do what your boss tells you to do, and you are supposed to grin and bear it. Your time will come because Korea, like Japan, had automatic advancement by seniority at least until 1990s. Once you are the boss, you can order people around, much like the way you can order people around once you put in the time and became a sergeant.

I happened to work in such a place when I wrote the first post in my own series on gender and militarization in South Korea, and in which I noted that Korean corporate life often requires such a level of personal sacrifice for one’s superiors that, tellingly, even the Samsung Economic Research Institute acknowledges that “many workers…take it for granted that they have to tolerate anything in return for getting paid.” I should note however, that many readers thought my workplace was the exception rather than the rule, but be that as it may, the purpose of many of those things to be tolerated there boiled down to no more than the demonstration (and abuse) of superiors’ authority…and so too does sexual violence clearly emerge as one means – albeit, and I stress, only one, uncommon means – of doing so in the Korean military.

But I will further cover the effects on Korean gender relations and sexuality in great detail as I belatedly continue that series next month. In the meantime, let me leave you with the following passage from Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors: A Search For Who We Are (1993) by Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan to ponder, a book which had a great effect on my worldview and which frequently came to mind as I was writing this post (via Viraj’s Weblog):

(Source)

(Source)

We go to great lengths to deny our animal heritage, and not just in scientific and philosophical discourse. You can glimpse the denial in the shaving of men’s faces; in clothing and other adornments; in the great lengths gone to in the preparation of meat to disguise the fact that an animal is being killed, flayed, and eaten. The common primate practice of pseudosexual mounting of males by males to express dominance is not widespread in humans, and some have taken comfort from this fact. But the most potent form of verbal abuse in English and many other languages is “Fuck you,” with the pronoun “I” implicit at the beginning. The speaker is vividly asserting his claim to higher status, and his contempt for those he considers subordinate. Characteristically, humans have converted a postural image into a linguistic one with barely a change in nuance. The phrase is uttered millions of times each day, all over the planet, with hardly anyone stopping to think what it means. Often, it escapes our lips unbidden. It is satisfying to say. It serves its purpose. It is a badge of the primate order, revealing something of our nature despite all our denials and pretensions.

Update 1, February 2013: See The Chosun Ilbo and ROK Drop for some more recent statistics on sexual assault in the Korean military.

Update 2, February 2013: See Sociological Images for more on sexualized insults.

Very nice posting…..

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

Another great and informative post. It’s one thing to assume stuff like this happens, but another when you can actually see numbers as to how prevalent it is.

It’s a shame, really, that this happens, because sexual abuse and violence is an endless cycle. Someone loses power from being abused and tries to regain it by becoming an abuser, the very thing they hate so much. As much as I take pride in the sacrifices my forefathers have made to ensure I can live in a free democratic society, I must admit that the applications of power and sometimes lax policies regarding acceptable and unacceptable behaviour need to be changed in the military organizations of some (if not all) countries.

There was a story a few years ago in Canada where a soldier drowned himself (or had accidentally drowned, I can’t seem to find the story at the moment) after being hazed by superiors and when he was in the water, noone did anything to help him.

There’s also another news article about a soldier seeking government action after severe hazing he encountered. That story can be read here:

http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=M1ARTM0013152

LikeLike

Thanks. One of those rare cases where on the one hand it’s good to have actual numbers, but also bad in that they confirm the stereotype. Still, the necessary first step towards dealing with a problem is acknowledging that it exists.

Like you say, a strong theme that emerges is cycle of being abused and then abusing. But one worrying point to add to that in the Korean context, is the number of people who see their roles as authority figures as not so much opportunities to break that cycle, but more to treat inferiors as badly as they were once treated, a “reward” for tolerating abuse from their own superiors earlier.

Sounds like a generalization and complete exaggeration of course, but then I think only to people who’ve never lived in Korea really, and I’ll always remember the freshman students I taught in my first year here, inordinately angry that their major was being phased out at their university (no more freshman classes in that major the next year). When I asked why, I was told that it was because it meant they wouldn’t have any freshmen to pick on and do various duties for them and so on themselves when they became sophomores and juniors etc., let alone MA & PhD students.

LikeLike

That’s an interesting point about students and military alike hoping for a chance to deal out damage as they had once been dealt. Do you think that there is a general vindictiveness among the Korean population. It sounds almost like a tit-for-tat society. Instead of trying to get over one’s behaviour or seriously look at the cycles involved, they just give into emotion and remedy pain by dishing it out.

Although I understand that young adults and children are “scientifically-speaking” (up until mid-twenties in some studies) not fully developed in their reasoning faculties, but I’m surprised that freshman students would jump at the opportunity to haze other students. I would have thought they would just let it go.

I know the societies are almost incomparable, but when I went to high-school and university, the whole atmosphere of masculine competition and trying to “prove something” just went out the door. People just moved the hell on from such behaviour, except for emotionally troubled individuals. <—– NOTE

Perhaps Korea has to look deeper into itself to see the troubling and possibly far too common trend of male aggression.

LikeLike

The freshmen being angry at not having other freshmen to lord over, at least, was just reported to me by a few students moaning about in my class (and 10 years ago at that), so I’m not sure how accurate or representative it is.

I’m pretty certain of the fact that Masters students here though, do the vast majority of their supervisors’ day to day work though, like marking undergraduate essays, even much of their research (for which they’ll receive no credit), as well as mundane things like making coffee, cleaning the office, and picking up his or her dry-cleaning.

Sucks to be the MA student of course, but I can sympathize a little with students completely used to life like that and contemplating having to do everything for themselves with no helpers later on.

That’s just between professors and Masters students though, don’t know what was involved in relationships between different years of undergraduate students; hell, that there’s any duties due from younger ones to older ones may just be in the latter’s heads really. But regardless, bear in mind that unlike in Western universities, Korean students tend to from friendships with and do all classes with the same group of students doing their major that they came in with (ie freshmen bio with freshmen bio, sophomore computing with sophomore computing etc. etc.), divisions compounded by Koreans’ habit of never referring to anybody as simply their “friend,” but rather “senior” or “junior” depending on their age.

Hell, kinda glad I didn’t go to a Korean university…

LikeLike

In the first table it states that there was 1 victim for forced masturbation and then 24 witnesses?

I stopped reading there as I think there may be other inaccuracies and its one long ass article.

LikeLike

It isn’t an inaccuracy: of the people interviewed, 1 person reported that he personally was the victim of forced masturbation, and 24 witnessed other people being the victims of it. Perhaps if you had a longer attention span you might have realized this.

Probably there were more direct victims, but they were reluctant to reveal it, for reasons explained in the text.

LikeLike

Absolutely stunning post, James.

This is one of your better ones, which is saying something because you have written many fantastic posts.

I thoroughly enjoy your writing, perspective and this blog.

-arvan

LikeLike

Wish I could think of something more sophisticated to say, but in the meantime: thanks again! :)

LikeLike

Wow, very informative post. From what you posted, it’s not just sexuality and military rank issues going on here, but class relations as well. Officers picking on rich kids and such, simply because they were (presumably) from a wealthier background. The Korean military needs some serious reform!

LikeLike

Actually, class and other issues of privledge are very important, and some people theorize that one reason student protests were often met with such violence on the part of police and soldiers during the 80’s was that the ranks were filled with young men from the countryside who were mostly denied opportunities to do things like go to college, so class issues aggrivated and increased the violence of the encounters.

I’ll ask my boyfriend and host brother about their time in the military, although both their experiences seem to have been atypical.

LikeLike

Thanks Mo, and good point about the 1980s protests Gomushin Girl: that sounds very plausible.

LikeLike

Reading this makes me glad that we don’t have national service here!

We already here some “interesting” things (ie horrible, bizarre, and WTF) which happen from time to time.

LikeLike

I’m sort of surprised that the interviewees reported “hugging” as sexual abuse, because in a country where physical contact between men is not deemed so homosexual…..

LikeLike

When the hugging is not wanted, I guess that’s where the abuse part comes in. It’s one thing to hug a friend, but another to have a military superior you only met a few months ago do it. Besides, a military superior takes advantage of his/her position to do this, whereas a friend usually doesn’t have the authority to get away with such things, so when it’s done, it’s usually allowed because the person is a friend.

LikeLike

Hmm, is hugging, touching in general considered more normal in Asian countries? I’m not sure I would consider the hugging, kissing (which seems odd anyway) or touching necessarily to be sexual abuse. Definitely, its harassment, but is it sexual in nature?

Ah, and this caught my attention. “Among perpetrators, 83% had experienced sexual violence in the military when they had been lower ranked soldiers. This feature of high number of perpetrators having previously experienced victimization themselves could be seen as the most unique feature of sexual violence among men in the military.”

Like Curtis was saying, it is an endless cycle unless greater efforts are made to address and educate people about this problem.

LikeLike

I admit that I too am a little puzzled by all the hugging: I do accept that it is abuse in a literal sense at least, just like – as far as I know – simply touching someone can legally be considered assault, and I also accept that it is abuse for the reasons Curtis gives too.

However, I still find it very difficult to imagine how hugging someone that doesn’t want to it can be an effective means of demonstrating one’s authority over them to others, and their masculinity as a whole. Or in other words, while that narrative certainly works for the other forms of abuse, I’m struggling to view forced hugging in the same terms. Perhaps there are indeed cultural overtones to hugging, hinted at by HiExpat, that weren’t really addressed by the authors?

Regardless, while the other forms of abuse seem self-explanatory, I guess the article should really have provided a definition of forced hugging at least, and elaborated more on what occurred and what it implied exactly.

LikeLike

Hmmm was regular skinship taken into account… ? The results would be very different if the people giving the information were asked to describe the sexual abuse then the answers were documented versus being asked “were you hugged” but hugging and physical contact is different in Korea than in North American cultures…. you don’t have to apologize when bumping into strangers and friends do things like shoulder touching and leaning on each other and such… But if skinship was dealt with and the results are accurately reported as not skinship but sexual abuse then I can see how hugging can be an assertion of power. You’re forcing a level of intimacy that hasn’t been consented to.

LikeLike

Korean military is far worse than US prisons. Although sexual abuse statistics look similar, at least in US prison you wont suffer from malnutrition, eating diseased animals culled and discarded by livestock industry, or get used as unpaid forced labor by government or even civilian construction projects.

LikeLike

Hi,

Thank you for your evaluation of the article previously – your updates on statistics (up until about 2013) and your thorough overview of the article was most insightful (especially having read the article myself, your post gives a little more context with a cross-comparison to other related articles/online sources).

I was wondering, are such cases still common in our present-day 2018; should it be, would you have any statistics on its frequency, or case studies/stories which we can look into?

Thank you so much for this article, and I look forward to your reply!

LikeLike

Hi DB,

Thank you for your comment, and I’d like to help, but I’m afraid I’ve never really revisited this topic sorry. I have continued to hear of many cases of sexual harassment and abuse in the Korean military in the 8 years since writing though, complicated by the “anti-gay witchhunts” a couple of years ago, so my strong impression is that they remain endemic, systematic problems.

On the other hand, it’s also true that the Korean military has been experiencing severe manpower shortages in recent years because of the low birthrate, so in response it’s been dramatically improving conscripts’ living conditions in order to encourage men (and women) to consider the military as a career. That has included allowing much more communication between conscripts and family members and girlfriends and so on (for instance, I even read recently that the military is considering allowing conscripts to have their own smartphones soon), which if so would do a lot to mitigate the culture of isolation and unaccountability that enables the abuse. How deeply and how widely things have genuinely changed (and are changing) though, I couldn’t say personally sorry. Best of luck with your own investigation! :)

LikeLike