Kim Jiyoung: Born 1982 scores points for its raising of numerous feminist issues, but its treatment of them is frequently quite superficial. Here’s how one scene should have been handled differently, shattering stereotypes and suggesting solutions in the process.

Estimated reading time: 8 minutes. Photo by Gabe Pierce on Unsplash.

Estimated reading time: 8 minutes. Photo by Gabe Pierce on Unsplash.

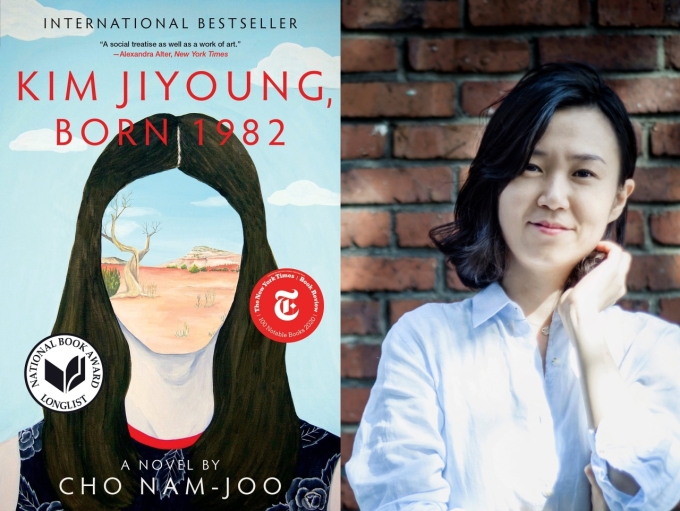

I didn’t like the novel Kim Jiyoung: Born 1982 much at all. There, I said it.

It’s basically a Korean Feminism 101 compendium, which means it didn’t really teach me anything new. Its constant shoehorning of facts and statistics into the narrative ruined it as a work of fiction too. But the biggest flaw was Jiyoung’s constant, infuriating lack of agency, with its flipside that author Cho Nam-joo didn’t really offer any solutions to the numerous hardships she faces either.

That doesn’t mean those hardships aren’t well-described. Like I said in my earlier review, I don’t think it’s a bad book at all. If you personally learned a great deal from it, and/or laughed, cried, and seethed in anger alongside Jiyoung, then I’m hardly going to claim that my own disappointment and frustration mean I’m somehow a much better, more knowledgeable feminist than you.

But Jiyoung’s lack of agency, and Cho’s lack of solutions, are absolutely a hill I’m prepared to die on. One scene in the film set in a subway toilet, albeit not mentioned in the book, illustrates both very well.

In it (55-56:00), Jiyoung (played by Jung Yu-mi) has to get off the subway to change her bawling infant daughter. Once that’s done, she realizes she needs to pee herself, but struggles in the narrow cubicle to hang up her heavy bag with her daughter strapped to her chest. Then, before she attempts again, she eyes the walls and lock nervously, remembering a recent molka (spycam) incident at the place she used to work. The scene then shifts to her home, implying she gave up and went there instead.

At first viewing, it’s difficult to find any fault here at all. Given that the burden of childcare falls overwhelmingly on women, then more men—or, indeed, more unsympathetic childless women—sometimes really do need to be literally shown just how much effort that actually involves. So too, do more men need to realize how stressful it is having to worry about being secretly filmed literally every single time you used any toilets outside of your home, as well as the potential health consequences if you understandably chose to avoid them.

Admittedly, that may seem like a lot to ask of a one-minute scene. Yet with just a little tweaking, it could have achieved those aims very effectively and forcefully. Instead, it largely fails, for three reasons.

The first is because, ironically, guys can relate to the practical difficulties. The indignity of using a cubicle while wearing a suit and carrying a backpack, desperately trying to prevent either from touching all the urine and smokers’ spittle on the floor, is absolutely no joke. As for childcare specifically, my ex-wife would naturally take our daughters with her to the female toilets when they were young, but it’s not like I wasn’t often in just as awkward and uncomfortable situations with them in other cramped locations.

Devoid of any wider context then, which I’ll provide myself in a moment, men’s own issues with using cubicles can mean women’s complaints fall on deaf ears, let alone calls to make women’s toilets bigger than men’s. (In fact, some men even consider the proposal to be reverse-sexism.) This lack of sympathy is misguided, of course, but I can understand it—unless men are flat out told or shown why not, it’s perfectly reasonable to assume that more cubicles in place of urinals suffice for women’s need to sit down. That women somehow still have to queue nonetheless, delaying everyone? Pop culture reveals that’s just their own fault, thanks to all the primping, preening, and gossiping that really goes on in there.

Next, the scene doesn’t do enough to convey the visceral fear of spy cameras. This is indeed much harder for men to relate to, because they never have to think about them when using public toilets. So, something much more forceful than Jiyoung’s brief nervous glances was required.

Best would have been a tweak to an earlier scene, which I’ll outline in a moment. But as an emphasis in this one, a more realistic cubicle should have been shown, with every nook, cranny, screw, bolt, and indent jammed with toilet paper and gum. Rather than the toilet the scene was actually shot in, which, complete with a rare heater, was easily the most pristine in Korea, seeing what it’s actually like in women’s toilets would surely have rammed home just how big of a problem spycams are in Korea—in a way that abstract news reports never could.

Image source: The Fact.

Image source: The Fact.

That earlier scene (44:30-47:30) is where Jiyoung’s former coworkers discover a spycam had been set up in one of the female toilets, and that their male coworkers had been sharing the videos, followed by meeting Jiyoung in a coffee shop to let her know. In hindsight, it’s all over surprisingly quickly. Whereas in the book, the incident is dealt with over three pages, and among the many grave consequences the coworkers reveal in those is that one victim overdosed on meds—possibly intentionally. This is omitted entirely in the film, but fits with the film’s much more kid-gloves, family-friendly tone overall (In particular, Jiyoung’s husband, played by Gong Yoo, is a vastly more sympathetic and likeable character than in the book. Perhaps a truer portrayal was rejected as harmful to his image?). In its place, the coworkers are not so much in tears as almost laugh off the affair, one joking about borrowing Jiyoung’s daughter’s diapers from now on.

Not only would I have absolutely kept that line about the coworker’s potential suicide instead, I would have devoted a minute to visiting her in hospital too. Was that not worth it to show that spycams have very real, devastating effects on people’s lives?

But if I only had an extra minute’s grace, I would use it to shift Jiyoung’s toilet scene to a few years earlier in her life, before she stopped working to have her daughter. She would be in her smart workclothes and high heels at a hweshik, an (effectively mandatory) after-work dinner with her boss and coworkers, and have to go to the toilet as everyone was preparing to leave to go to a second round at a bar. She would take longer than many of the men would like, because—and herein lies that context, as explained by Sora Chemaly in Time. Because, yes, it really does need explaining, as it’s not at all just about sitting vs. standing:

Women need to use bathrooms more often and for longer periods of time because: we sit to urinate (urinals effectively double the space in men’s rooms) [note also, “Women empty their bladders more frequently than men and take longer – an average start-to-finish time of 60 seconds for men, but 90 for women”—James], we menstruate, we are responsible for reproducing the species (which makes us pee more), we continue to have greater responsibility for children (who have to use bathrooms with us), and we breastfeed (frequently in grotty bathroom stalls). Additionally, women tend to wear more binding and cumbersome clothes, whereas men’s clothing provides significantly speedier access. But in a classic example of the difference between surface “equality” and genuine equity, many public restrooms continue to be facilities that are equal in physical space, while favoring men’s bodies, experiences, and needs.

So when Jiyoung did rejoin the group, one of those impatient men could have made an all too common complaint or joke about holding everyone up for the sake of putting on her lipstick. To which she could have angrily pointed out it wasn’t her fault, for any number of the above reasons she could have chosen to highlight (and/or by having to spend time ramming toilet paper into all those potential camera holes, would have killed two birds with one stone). She could have followed that the obvious solution of “potty parity”—mandating 2:1 or 3:1 female to male toilet size ratios in all new building plans, and/or building more shared toilets—wasn’t at all reverse-sexism, but would benefit both women and the men who had to wait for them.

Indeed, this scene would not be unlike the—MILD SPOILER—final scene in the film, in which Jiyoung actually does confront a guy who accuses her of being a “mom roach,” living the high life gossiping in coffee shops, a parasite on her rich husband and the hard workers who pay the taxes for her holiday of maternity leave. Which is a rare credit to the film, and certainly a better alternative to her just slinking away in shame like in the book, then getting gaslighted by her husband when she complains about it. However, as it’s the conclusion to what’s actually an extremely saccharine-feeling film overall as discussed, it’s somewhat underwhelming as a climax—SPOILER ENDS.

Indeed, this scene would not be unlike the—MILD SPOILER—final scene in the film, in which Jiyoung actually does confront a guy who accuses her of being a “mom roach,” living the high life gossiping in coffee shops, a parasite on her rich husband and the hard workers who pay the taxes for her holiday of maternity leave. Which is a rare credit to the film, and certainly a better alternative to her just slinking away in shame like in the book, then getting gaslighted by her husband when she complains about it. However, as it’s the conclusion to what’s actually an extremely saccharine-feeling film overall as discussed, it’s somewhat underwhelming as a climax—SPOILER ENDS.

With an extra minute still, I would also add a scene of her as a teenager, suffering from bladder and dehydration problems that her much fawned-over brother avoided, because he could obviously better endure Korean schools’ notoriously dirty and outdated toilets. But I digress. The point is, Jiyoung in the subway toilet with her daughter is just one scene of many that could have been dramatically improved. I curse having read the book Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-made World by Leslie Kern (2020) in particular, which means I can just no longer unsee the flaws in the scenes in either the book or film. Although, given the former’s popularity, now I do appreciate the value of seeing one’s own lived experiences represented in print, even if Cho neither presents Jiyoung as a role model nor offers any potential solutions to what she faces.

Those responsible for the film however, could have and should have responded to the backlash by taking up that mantle, exploiting the potential of the new visual medium to shock and shame. Instead, they wasted the opportunity by making it as saccharine as possible, all for the sake of people who had probably never actually read the book and were even less likely to watch the film.

Related Posts:

- March Book Club Meeting: “Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982” by Cho Nam-joo, Wednesday 15 March, 8:15pm KST

- Korean High School Girls Complain They Can Barely Breathe in Uniforms Smaller Than Clothes for 8-Year-Olds

- How Slut-Shaming and Victim-Blaming Begin in Korean Schools

- The Hidden Roots of Korea’s Gender Wars

- “저의 몸과 저의 섹슈얼리티에 대한 이야기를 해보려고 합니다. 이것은 실로 부끄러운 고백이어서 저는 단 한 번밖에 말하지 못할 것 같습니다. 그러니 가만히 들어주세요.”

- Hyundai Fit-Shaming Korean Girls

- The Korean Conscription System Promotes a Servile, Subordinate, Sexually-Objectifying View of Women. Here’s How.

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)