As in, how many Korean women are pregnant when they walk down the aisle? How many get married after giving birth? How many mothers don’t get married at all? And how have public attitudes to all those groups changed over time?

As in, how many Korean women are pregnant when they walk down the aisle? How many get married after giving birth? How many mothers don’t get married at all? And how have public attitudes to all those groups changed over time?

I’ve spent the last two weeks trying to find out. It’s been surprisingly difficult, apropos of a subject many couples would prefer to keep under wraps.

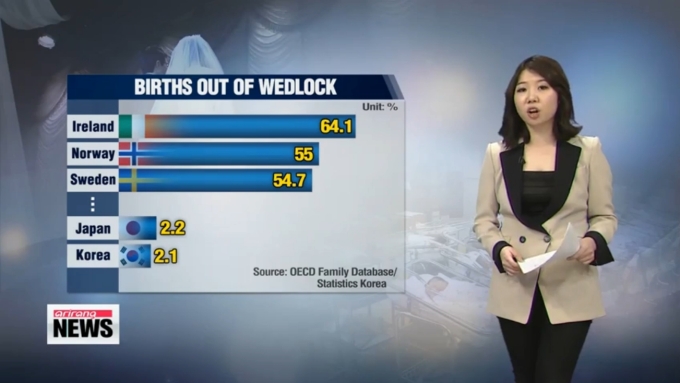

It all started with this Arirang news report, thanks to the interesting way it framed Korea’s low birthrate problem:

An aging population and low birthrate — two problems that Korea and Japan have in common and are trying to solve.

And since having children out of wedlock is considered socially unacceptable in either country, the focus is on encouraging people to get married.

So the countries share similar problems, but do the people of Korea and Japan share similar views on marriage?

A report by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs says NO…

(Arirang, December 4, 2014; my emphasis)

My first thought was that a focus on marriage made a lot of sense. From that chart alone, you can guess that there is considerable prejudice against single mothers and their children in South Korea, to the extent that Korea was (and is) notorious for overseas adoption. In 2008, Seoul National University Professor Eun Ki-Soo saw a direct relationship between such attitudes and Korea’s low birthrate problem:

According to the International Social Survey Program (2002) and Korean General Social Survey (2006), Korea “had one of the highest number of respondents who believed ‘people who want children ought to get married.’ The only countries that scored higher than Korea were the Philippines and the United States, but the differences in the scores were not statistically significant….In the face of such strong social norms regarding marriage and reproduction, young people who are unable to marry also may not feel like they can have children. Such a phenomenon is manifested in contemporary Korean society in the form of a low fertility rate”

(Eun, pp 154 & 155; see bibliography)

Likewise, two weeks ago the Park Geun-hye Administration pinpointed the cause of Korea’s low birthrate “to be the social tendency to marry late”, and announced that it aimed “to buck that trend by rectifying the high-cost marriage culture in Korea, increasing the supply of rental housing for newlyweds and expanding medical insurance benefits for couples with fertility problems.” (Note that the number of marriages in 2014 was estimated to be a record low, with 50% of 30-somethings seeing marriage as “dispensable”.) Last week, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs researcher Cho Sung-ho reaffirmed that “it is necessary to support young people so they can experience dating, marriage and childbirth without too many difficulties”, and that “In order to do that, creating quality jobs and support programs for job seekers must be introduced as part of measures to tackle the country’s low fertility rate” (source, below: The Hankyoreh).

Yet in saying young people need support, surely Cho is is just reiterating Korea’s — and other developed economies’ — biggest social problem of the 2010s (and likely 2020s)? And what use is there in making it easier for young Koreans to get married, when married couples aren’t having enough children in the first place?

Simply put, Park Geun-hye’s announcement feels disingenuous, distracting from the difficult reforms of Korea’s patriarchal work-culture needed.

But my second thought was on the Korean women that do get knocked up. Specifically, those that do so before or without ever getting married, the only two groups I’ve ever heard the term used for (quick question: does anyone use it for married women, except in a humorous sense?). First, because that 2.1% rate of out of wedlock births is actually the highest it’s been in decades, albeit by no means because attitudes have softened over time:

Available statistics [Korea Statistical Yearbook #55, 2008] indicate 6,141 illegitimate child births in 1990 and 8,411 in 2007, representing, respectively, 0.66% and 1.69% of the total child births; a percentage rise that seems mainly due to the general fall in child births from 1990 to 2007 (931,602 in 1990, and 497,188 in 2007).

(Payen p. 72, my emphasis; see bibliography)

(For comparison’s sake, there were 403,500 childbirths in the first 11 months of 2014, while a February 4 estimate put the yearly figure at 430,000. Update: a February 26 report put it at 435,300, the second lowest level ever.)

Second, because despite everything I’ve written above, I was surprised that the the rate wasn’t higher still. Why? Partially, because of personal experience, one of my wife’s cousins having a child before getting married, but no-one in her village treating that as unusual or something to be embarrassed about (she later married and had a second child). And mainly, because that lack of a reaction was already explained by the following comment left by @oranckay on my 2008 post, “Why Korean Girls Don’t Say No: Contraception Commercials, Condom Use, and Double Standards in South Korea.” While the post itself has long since been completely rewritten, and the comments deleted (sorry!) because that meant they no longer made sense, you’ll soon see why I decided to save his one:

(Note that it was written in reaction to my surprise and confusion at public outrage at Korean female celebrities  revealed to be having premarital sex — how times have changed!(?) — but the lack of any negative reaction to regular announcements of celebrity pregnancies before marriage, one example mentioned in the post being Kwon Sang-woo’s and Sohn Tae-young’s that September {Source, right: Dramabeans}.)

revealed to be having premarital sex — how times have changed!(?) — but the lack of any negative reaction to regular announcements of celebrity pregnancies before marriage, one example mentioned in the post being Kwon Sang-woo’s and Sohn Tae-young’s that September {Source, right: Dramabeans}.)

…I think one needs to take into account that not all pre-marital sex is the same. There is a difference between just having sex and having sex with someone you are going to, or intend to, marry, and traditional/Joseon and even 20th Korea saw this as a big difference. Having sex on the premise of, and as consummation of, commitment, was the normal, socially acceptable way to have pre-marital sex. So valued was a woman’s virginity that a decent man could only sleep with her if he was ready to “take responsibility for her,” as the saying would go, and so on, because that’s what sleeping with her was supposed to imply. Fiction and non-fiction narratives (many known to me personally) are full of this kind of thinking. I know couples that decided not to have sex because they weren’t sure they were getting married, that didn’t have sex because he was going to the military and he wanted to be sure he’d come back alive before permanently “making her his,” as that would be too traumatic for her, and of couples that lived together (and obviously were having sex) before being married and it was acceptable because they were going to marry, had family approval, but couldn’t marry because maybe the girl’s elder sister wasn’t married off yet or they were both still in college but both sets of parents wanted to get them married after graduation, or one of those odd reasons. Maybe no money; whatever.

Anyway, the best example I can think of all this is classical Korean prose fiction (since that’s all I ever think about). There is plenty of premarital sex in traditional Korean prose fiction (“novels”), graphic in only a few exceptions I’m afraid, but we are at least told that it is happening. The reason this fiction wasn’t thrown into the flames at Confucian book burning parties (and there were Joseon poets who did indeed call for novels to be burned for their bad influence) was because whenever there is pre-marital sex the parties always end up married. In fact you know they’re going to marry before you get to the end because they slept together. The most readily available example would be “the most classic, all time” story Chunhyang Jeon. The most “대표적” Korean story of all time and it involves “happily ever after” pre-marital sex. So it’s one thing for a celebrity to have a bulging waistline at her wedding and another for a video to surface of her having a romp with one of her producers, for example, or even to shoot a fully nude bed scene in a feature film.

Update: Via KLawGuru, comes news that there used to be a law that was very much in the same vein, and which was only very recently repealed:

In 2009, a crime called “Sexual Intercourse under Pretense of Marriage” was ruled “unconstitutional.” It used to be a crime for a man to have sex with a woman by deliberately deceiving her into believing that he would later marry her. To learn more, click here.

But to reiterate, just how common are those bulging waistlines at weddings? And (how) have people’s attitudes changed over time? After seven years, it was high time to do a proper follow-up on oranckay’s comment. I hit the books.

(Sources: left, 나는 수풀 우거진 산에 갔더니; right, Opeloverz)

(Sources: left, 나는 수풀 우거진 산에 갔더니; right, Opeloverz)

Unfortunately, I was unable to find much at all about premarital pregnancy and childbirth specifically. Instead, I spent much of the next two weeks collecting and typing up a lot of fascinating, related information about attitudes towards virginity, premarital sex, sexual experience, cohabitation, and contraceptive use, forced as I was to deconstruct and think about all aspects of the phenomenon (read: desperately search for any related topics whatsoever in indexes). Then I realized that I was going about things entirely the wrong way, and should: a) devote a separate post to those next month; and b) rely on someone who’s already done all the hard work for me instead. Sure enough, just a couple of pages of the right book would literally speak volumes:

…In the mid-1980s, cohabitation was not rare. [Yoon Hyungsook, pp. 18-24] writes that three out of ten marriages concerned cohabitating couples, and that all these couples even had children at the time of their wedding. Although these couples were not officially married, it was “only” legally, not in the eyes of the villagers. The important point to mention is the fact that all these cohabitations were approved by both spouses’ in-laws, with the wife fulfilling her role of daughter-in-law as if she was legally married. When the wedding ceremony comes later, delayed because of financial difficulties, it confirms a relationship, ascertains the position of the woman in her husband’s family, and makes the couple fully adults in the eyes of society.

So, cohabitation did exist, was not rare, and was often a living arrangement used by people of poorer classes for whom marrying meant heavy expenses. Kendall (p. 123) writes that “by the 1970s cohabitation before marriage was common among village children who worked off the land and among rural migrants to the cities. It remains a common practice among urban workers.”

Spencer and Kim Eun-shil also delve on cohabitation in their studies about female migrant factory workers. But, while for women of Spencer’s research, this living arrangement was not the norm, it was most common in Kim’s research; a difference possibly related to the 20 years that have passed between the two studies and changes of attitudes and practices in relation to marriage and cohabitation (1970-1990).

(Payen, pp. 87-88. Kendall and Spencer books mentioned are below; see bibliography for Kim.)

(Source, left: Google Books; right, Amazon)

(Source, left: Google Books; right, Amazon)

Of course, I acknowledge that the above is just a indirect confirmation of oranckay’s comment really (although that is still valuable), and I can’t possibly do justice to Payen’s thesis on cohabitation in Korea here, nor on how and why it’s actually become less common since the 1990s. In the comments section below though, Gomushin Girl provides a good summary of one of the most important factors behind that shift:

[One] important aspect here is the socioeconomics of it all . . . earlier research like Kendall’s and Spencer is looking at a Korea that was either still relatively poor or just emerging as a major economy. They’re already reporting a very class-based variance in attitudes towards premarital sex and pregnancy [and cohabitation—James], with higher socioeconomic status associated with lower acceptance. I’m not surprised to see that as Korean wealth increased, people increasingly adopted attitudes associated with wealth.

Also, we shouldn’t be left with an overly sanguine, no nonsense image of attitudes to premarital pregnancy in the past either, as the opening to a Korea Herald article about adoption linked earlier attests:

In 1976, a 17-year-old Korean girl gave birth to her first child. A few months before the delivery, she had been forced to marry the man who raped and impregnated her.

“That was the norm at the time,” Noh Geum-ju told The Korea Herald.

“When you get pregnant as an unmarried woman, you have to marry the father of your baby. Other options were unthinkable.”

(The Korea Herald, 28 January, 2014)

Update: Here’s another example from a celebrity couple, currently involved in a domestic violence case:

Seo Jung-hee [a former model and actress] said her husband [comedian-turned-clergyman Seo Se-won] sexually assaulted her at the age of 19, so she had to marry him, and she had been his virtual prisoner for 32 years. She said she was too afraid of him to seek a divorce and had to endure because of the children.

(The Chosun Ilbo, 13 March 2015)

I also read that, traditionally, if a suitor was spurned by his intended bride, he could consider raping her to secure her family’s consent. Mostly, due to the shame involved, but of course the imperative was all the greater if she became pregnant. I can’t remember the exact reference sorry (I will add it if I do), but I did find the following:

…The “proper” women must remain chaste, and the requirements of being chaste are utterly crazy. As a rule, a traditional Korean woman carried a small silver knife. The knife is for self-defense, but not the kind of self-defense that you are thinking. The knife is there to kill yourself with if you are about to be “disgraced”. Realistically, “disgraced” means “raped”. However, technically “disgraced” meant any man other than your husband touching you.

One story during the Joseon Dynasty speaks of a virtuous woman who, because a boatman held her hand while helping her into the boat, either jumped out of the boat and drowned herself or cut off her own hand, depending on the version. It is unlikely that this story is true, but this was the moral code to which traditional Korean women were supposed to aspire. In a similar horrifying vein, rape-marriages – forced marriage to a man who raped you – happened regularly until late 1970s, since living with the rapist as a proper woman is better than living as a fallen woman.

(Ask a Korean!, December 3, 2008)

But we were talking about attitudes towards and rates of premarital pregnancy in the 2010s. Which, to conclude this post, naturally I would end up learning more about from the following Korea Times article than from my entire 20-year collection of Korean books(!). Some excerpts (my emphasis):

…premarital pregnancy is now humdrum, even among people who are not stars.

In a survey that consultancy Duo Wed conducted between June 1 and June 14, one-third of 374 newlyweds questioned said the bride was pregnant when they married.

Of these couples, 92.1 percent said their babies were unexpected…

…Changing perceptions on premarital pregnancy are also affecting other related industries: wedding dress rentals and tourism businesses.

…Changing perceptions on premarital pregnancy are also affecting other related industries: wedding dress rentals and tourism businesses.

A wedding dress shop director says she has recently noticed more pregnant brides-to-be.

“They look for dresses depending on the number of months they are pregnant,” says Seo Jung-wook, director of Pertelei, in Cheongdam-dong, southern Seoul.

“Women who are three to five months pregnant fit well into a bell-line dress, while those further into their pregnancy often look good in an empire-lined dress.”

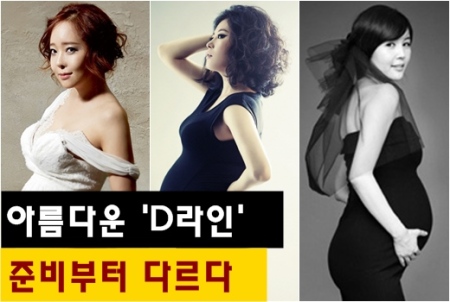

Other dress shops have their own selections of “D-line dresses” in stock because of increased demand [which no longer have to be custom made and bought].

Sigh. I’d always assumed that D-lines were just a joke sideline (no pun intended) to Korea’s body-labeling and shaming craze. I should have known better.

Continuing:

…The tourism industry is also catching up with the trend. Instead of honeymoons, travel operators promote “babymoon” programs for pregnant newlyweds.

These programs avoid placing any burden or stress on the baby or the mother.

Kim Jin-hak, representative director of Honey Island, a tourism agency specializing in services for newlyweds, says the agency’s “babymoon” program is popular with brides…

(The Korea Times, July 23, 2013. Source, above: WStar News)

(Source: Lotte Tour)

(Source: Lotte Tour)

As always, this is just a start. For many follow-up posts, I plan to look at journal articles (which will probably be more fruitful), Korean-language sources, plus blogs about or often covering marriage and pregnancy in Korea, such as the sadly now defunct On Becoming a Good Korean (Feminist) Wife. Plus, of course, any readers’ suggestions (for books also!), which will be much appreciated.

Please pass them on, and/or tell me in the comments about any of your own experiences and observations about premarital pregnancy (and so on) in Korea. Do you personally know any women who were pregnant at their weddings? (Or were you or your partner yourself/herself? By all means, please feel free to comment or email me anonymously!) What were their family’s and friends’ feelings and reactions? Was the couple effectively forced to get married, in a case of “사고 쳐서 결혼” (lit., “marriage by accident,” or a shotgun wedding)? How about those of you with Korean partners? Did your foreignness make a difference? Thanks!

(For more posts in the Korean Sociological Image Series, see here.)

Bibliography

— Ki-soo, Eun “Family values changing—but still conservative”. In Social Change in Korea, edited by Kim Kyong-dong and The Korea Herald, 146-156. Korea: Jimoondang, 2008.

— Kim, Eun-shil “The Making of the Modern Female Gender: the Politics of Gender in Reproductive Practices in Korea”, (PhD dissertation, University of California, 1993) [Referenced by Payen]

— Payen, Bruno “Cohabitation and Social Pressure in Urban Korea: Examining Korean Cohabitants’ Behavior from a Comparative Perspective with France” (MA thesis, The Academy of Korean Studies, Seongnam, 2009).

In addition to social stigma, we should also look at the availability of abortion in SK. While technically illegal, it’s widely available and extremely common – and, outside the admittedly sizable evangelical Christian community, viewed as an acceptable moral and social choice. Many women in other countries where abortion is technically legal still face substantial obstacles to obtaining one. An American woman, depending on where she lives in the US, may face substantially more barriers to getting an abortion than a similarly positioned woman in Korea.

Another phenomenon, although I suspect it’s a rather small factor, is the idea of using pregnancy to precipitate a marriage that is otherwise unlikely to happen. I know of more than one couple that dealt with parental disapproval of the match through a deliberate out-of-wedlock pregnancy to force the issue. Many parents will relent and allow the marriage rather than deal with the social disgrace.

Another important aspect here is the socioeconomics of it all . . . earlier research like Kendall’s and Spencer is looking at a Korea that was either still relatively poor or just emerging as a major economy. They’re already reporting a very class-based variance in attitudes towards premarital sex and pregnancy, with higher socioeconomic status associated with lower acceptance. I’m not surprised to see that as Korean wealth increased, people increasingly adopted attitudes associated with wealth.

LikeLike

Sorry for the late reply, and good points (as always). I’ve added the last paragraph to the post :)

LikeLike

Great article! Yeah, can you believe such a crime lasted that long.

LikeLike

Thanks. And well, actually I can believe it lasted that long considering how long the adultery one did, and how important a woman’s modest, virginal reputation was (and still is; I’ll cover that in the next follow-up post). I’m curious though, what constituted evidence of alleged promises to marry, and how that would have been obtained? Even obtaining proof that the alleged victim and perpetrator had a sexual relationship sounds difficult!

LikeLike

Yes, you are right. It was a very iffy crime to begin with. At the time it was ruled “unconstitutional,” only a very, very handful of people were being indicted at all. In a way, it was a crime akin to “fraud” (i.e., promise to marry vs. promise to pay back money). Usually, the couple would be cohabitating in a situation where the woman was (mistakenly) sure of impending marriage. This crime was repealed in my 1st year of law school. One less crime to study, I thought.

LikeLike

Thanks for the reply. For the follow-up post on attitudes to virginity, I’ll check if it’s mentioned in Payen’s thesis on cohabitation too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t know if you’ve heard of Twinsters before, but the trailer is out.

Also: Kim Hyun Joong threatened to kill his pregnant ex if she cheated on him.

LikeLike

Thanks. I had heard of both, but I always appreciate your letting me know about things.

News about Kim Hyun-joong did pop up a lot while I was writing this post, and I was naturally briefly interested when I heard about the pregnancy. But frankly I didn’t know who he was, and his drama with his girlfriend sounded very messy, so it didn’t really seem worth the time investigating. Unless you think there’s anything that would be generalizable to other Korean couples?

LikeLike

I think Kim Hyung Joong’s baby mama drama is relevant to Korea today. The ex girlfriend doesn’t want to marry him and doesn’t want to abort the baby either.

LikeLike

If you think so, I’m happy to be corrected :) , and I admit that it could be an interesting example for this post. It’s just that the (admittedly few) stories I’ve read about it just seemed to be full of rumor and hearsay, and focused on minutiae of text messages between them and so on, rather than placing what she’s doing in any kind of context or anything like that.

LikeLike

Update: Here’s a good write-up of the situation, albeit with more of an emphasis on Korean domestic violence issues than on premarital pregnancy (and rightly so).

LikeLike

Since the first image also shows a figure for Japan, I thought I would mention the research Ekaterina Hertog has made on unwed mothers in Japan. Her research is based on anthopological fieldwork in Japan with a number of interviews with single mothers. One of her perspectives is to look at the economic and legal structures that places single mothers in a comparatively less favorable position. Another of her focus points is to look at relations inside families and at how single motherhood may be perceived (by the mother’s parents for example) to affect the mother’s sisters in job seeking and job interviews.

She describes the results in a book from 2009 called “Tough Choices: Bearing an Illegitimate Child in Japan” (http://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=16035) and also in the lecture from 2013: http://podcasts.ox.ac.uk/i-did-not-know-how-tell-my-parents-so-i-thought-i-would-have-have-abortion

That said, I know that Korea is not Japan, but it might be a valuable perspective.

LikeLike

Thanks, those links do indeed sound interesting. Will listen to the podcast on the subway tomorrow :)

LikeLike