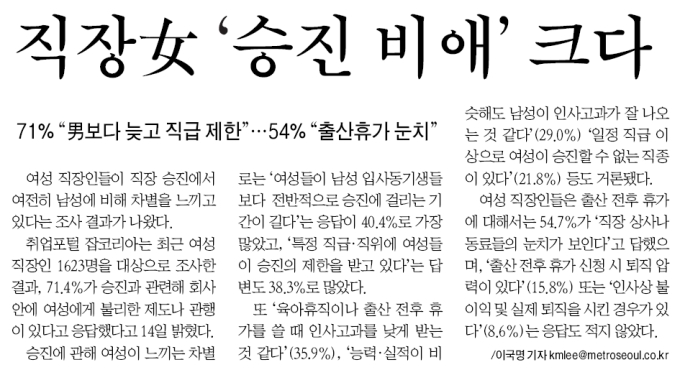

One recent study demonstrates the more of their fair share of housework and childcare fathers do, the more children they’ll probably have; another, the many entrenched workplace and social welfare practices that prevent Korean men from doing so. Loudly challenging the stereotypes and gender norms that discourage them, however, should be a no-brainer for policymakers.

Estimated reading time: 11 minutes. Photo by Annushka Ahuja from Pexels.

Estimated reading time: 11 minutes. Photo by Annushka Ahuja from Pexels.

A lot of things have to come together, for a successful dating, sex, or family life.

Sadly, those combinations elude most young South Koreans. Which is not to say you won’t still see plenty of couples out on dates in this warm weather, popping into love hotels, or families out for a stroll. But when you do, as @publiusterence points out in this insightful Twitter thread, notice also their expensive haircuts, clothes, smartphones, handbags, watches, strollers, and cars. Then you realize: some of the very best things about being human, which the vast majority of us deeply, instinctively aspire towards, are simply “becoming a privilege for the middle class and above.”

No wonder everyone else is so angry.

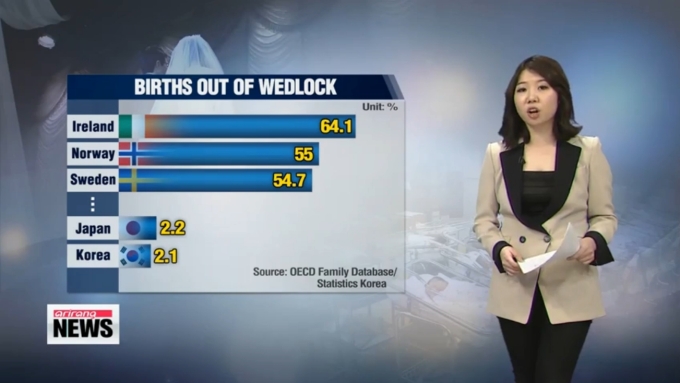

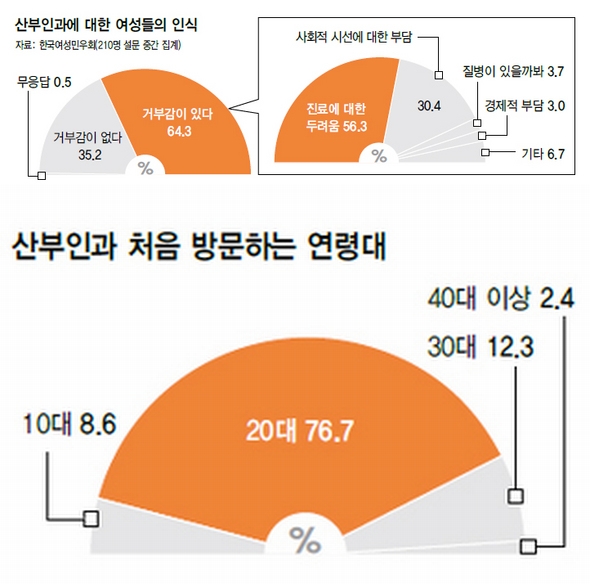

There are a host of familiar, intractable reasons for this increasing bifurcation of Korean life. Too familiar, really. Who amongst you hasn’t already read how the economy in Korea is so polarized for instance, that singles say they simply lack the time and money to go on dates or have sex, let alone ever getting married and owning a home? Or how heavily the importance and costs of education (PDF) weigh on the decision to have children? Which only married people can even ponder really, so daunting remain the stigmatization and legal problems suffered by single mothers, as well as the strong taboos against having children if the parents have no intention to marry?

Is it any surprise that on the day of writing, a poll revealed that over half of 20-somethings don’t plan to have children after marriage?

And so depressingly on.

Photo by Alex Green from Pexels

Photo by Alex Green from Pexels

Yet some of those reasons may also feel familiar, and personally and painfully so, because you’re in a similar position yourself—only you’re not in Korea. Which further begs the questions: to what extent are Korea’s own cultural and gender norms responsible for Korea’s world-low birthrate? Or, are they simply due to late-stage capitalism? How to tease the effects of each apart?

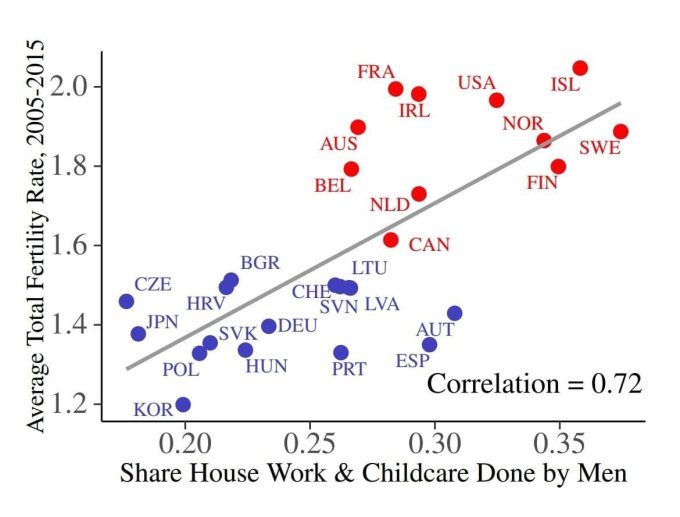

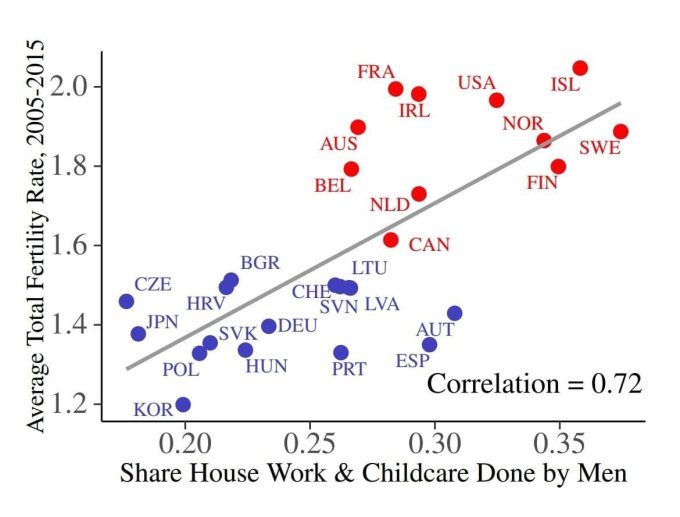

Such inquiries slide easily into a longstanding, ongoing sociological debate known as “convergence vs. divergence,” over whether the demands of capitalism force societies to adapt economically inefficient social, cultural, and gender norms as they develop, thereby making advanced capitalist societies resemble each other more over time, or whether some norms will endure regardless. Which is what makes the following graph, spreading rapidly on Korean Twitter, so interesting:

Source: Figure 16, “The Economics of Fertility: A New Era,” p. 32. Note that “Men” should more accurately say “Fathers.”

Source: Figure 16, “The Economics of Fertility: A New Era,” p. 32. Note that “Men” should more accurately say “Fathers.”

From the April 2022 “The Economics of Fertility: A New Era” by Matthias Doepke, Anne Hannusch, Fabian Kindermann, and Mich`ele Tertilt, a manuscript in preparation for the upcoming Handbook of Family Economics, unfortunately Korea is little mentioned specifically in the 129 page (but still fascinating) document. However, one of two potential takeaways is the seeming endurance and overwhelming influence of Korean cultural and gender norms. The dominant narrative projected by English-language commentators on Korean society after all, not least by myself, is that Korea remains a fundamentally sexist society. As BBC journalist Simon Maybin puts it in his August 2018 article, “Why I Never Want Babies,” with an iconic quote on this issue which I’ve often said myself (but am relieved to now have a much more reliable source for!):

A culture of hard work, long hours and dedication to one’s job are often credited for South Korea’s remarkable transformation over the last 50 years, from developing country to one of the world’s biggest economies.

But Yun-hwa says the role women played in this transformation often seems to be overlooked.

“The economic success of Korea also very much depended on the low-wage factory workers, which were mostly female,” she says.

“And also the care service that women had to provide in the family in order for men to go out and just focus on work.”

Now women are increasingly doing jobs previously done by men – in management and the professions. But despite these rapid social and economic changes, attitudes to gender have been slow to shift.

“In this country, women are expected to be the cheerleaders of the men,” says Yun-hwa.

Korean Sociological Image #92: Patriotic Marketing Through Sexual Objectification, Part 1

Korean Sociological Image #92: Patriotic Marketing Through Sexual Objectification, Part 1

More than that, she says, there’s a tendency for married women to take the role of care-provider in the families they marry into.

“There’s a lot of instances when even if a woman has a job, when she marries and has children, the child-rearing part is almost completely her responsibility,” she says. “And she’s also asked to take care of her in-laws if they get sick.”

The average South Korean man spends 45 minutes a day on unpaid work like childcare, according to figures from the OECD, while women spend five times that.

“My personality isn’t fit for that sort of supportive role,” says Yun-hwa. “I’m busy with my own life.”

Also, for your interest, and because far more people need to be aware of Kaku Sechiyama’s excellent book, Patriarchy in East Asia: A Comparative Sociology of Gender (2015), here is his summary (p. 164) of Korean surveys from a decade earlier. As a reviewer noted, “it is in Korea (South and North) where motherhood is most pronounced, as is a household division of labor by gender”:

However, @publiusterence’s example also suggests looking beyond the headlines, as well as our preconceived stereotypes. For in addition to demonstrating that even in the progressive, supposed feminist utopias of Scandinavian countries, fathers still only do a third of the housework and childcare as mothers, a second, slightly contradictory potential takeaway is that regardless of the country, having fathers pull their weight more will invariably increase the fertility rate.

Source: Figure 16, “The Economics of Fertility: A New Era,” p. 32. Note that “Men” should more accurately say “Fathers.”

Source: Figure 16, “The Economics of Fertility: A New Era,” p. 32. Note that “Men” should more accurately say “Fathers.”

Does that make it also a potential point of convergence between capitalist societies? Admittedly, to posit it as such may seem misguided, as considering childcare and housework to be primarily mothers’ responsibilities is the very definition of a gender norm in itself. But the alternative, writing off all Korean fathers as simply lazy and sexist, is not exactly fair. Nor does it offer much in the way of solutions.

Instead, surely it is more helpful to point out the many structural factors that prevent Korean fathers from doing more work at home (whether they actually want to or not), as well as to point out practical steps that can overcome those.

Addressing the elephant in room first however, that last—let alone this post’s title—is not meant to imply that Korean policymakers aren’t already well aware of those many structural factors. Also, that they defy easy fixing, simply by virtue of not having already been done so. For an excellent summary of them, I recommend the second recent study, “Revisiting the Gender Revolution: Time on Paid Work, Domestic Work, and Total Work in East Asian and Western Societies 1985–2016” by Man-Yee Kan, Muzhi Zhou, Kamila Kolpashnikova, Ekaterina Hertog, Shohei Yoda, and Jiweon Jun in Gender & Society released just a month before that graph. Some highlights (my emphases):

Since the 2010s, the Korean government has introduced a series of family policies such as paid parental leaves, subsidized childcare services, and flexible working to help women and men to balance work and life. Public and social expenditure in Korea increased from five percent in 1990 to ten percent in 2012, but the figures were lower than the OECD average. Yet some scholars have classified the welfare regimes in Korea and Japan as [our “Conservative” type], given the fact that the governments in these countries work closely with businesses and corporations in providing social insurance and pension schemes; the result is a high degree of stratification among occupations and between the employed and the non-employed.

The reason for this was the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, after which Korea underwent a revolutionary shift from having the most job for life, male breadwinner, “salarymen” in the world to having the most part-time and irregular workers in the OECD, as well as having one of the highest rates of self-employment. The important distinction is that those fortunate enough to secure “regular” jobs in large corporations make much more money and have far more fringe benefits than everyone else (hence all that money spent on children’s education; going to the right schools and universities is a must to secure such jobs). Also, as you can imagine, women make up most of the irregular workers.

Photo by Ketut Subiyanto from Pexels.

Continuing:

Our findings suggest that cultural norms interact with institutional contexts to affect the gender convergence in time use, and gender relations might settle at differing levels of egalitarianism. Furthermore, policies relying on family ties and women’s traditional gender responsibility for care provision, as in the case of Japan, Korea, and Southern European countries, will hinder progress in gender equality.

And today I learned:

In Japan and Korea, the gender gaps in paid and unpaid work time are large but the gap in total work time is relatively small; the gender convergence in paid and unpaid work time has been extremely slow and has even stalled.

Source: @BreeNewsome

Source: @BreeNewsome

Finally:

These findings reveal that policies relying on families as a key source of care provision, including those of Southern European countries, Japan, and Korea, prevent women from increasing labor market work and reducing their share of domestic labor. In addition, the persistently long work hours in Japan and Korea have created barriers for men to committing time in domestic work.

And yet, even if you can’t change the long working hours, the universal male military conscription, the general homosociality of Korean life, and so depressingly on overnight, something that can be put in motion is a clear, explicit, widespread government campaign at raising awareness about that graph, following by loud, well-publicized efforts at removing the outdated gender roles and stereotypes from our daily lives that sustain them.

This may sound somewhat naive, and certainly isn’t a magic bullet. Of course, various initiatives of this nature have already been going on for decades too. However, deepening them and enlarging their scope would be still relatively cheap, and uncontroversial. Moreover, given the direct correlation between fathers’ share of housework and childcare to the birthrate, what’s to lose for governments that have already spent billions on trying to raise the latter, to little effect?

Indeed, if as a selection of books recently reviewed in the Atlantic show, “social and political shifts are usually the result of sustained, unseen work,” then there is still far more that needs to be done before those shifts become visible:

Source: Wikitree via Naver.

Source: Wikitree via Naver.

For instance, when translating foreign language programs and films into Korean subtitles, government-television broadcasters shouldn’t be allowed to depict women usually using honorific speech (존댓말) to men and men usually informal language (반말) to women, an extremely common practice that is done regardless of the status of the characters and despite no such distinctions being made in the original language. (It was even done in The Return of Superman to BBC Dad and his wife here in Busan.) Likewise, private broadcasters who do should also be named and shamed.

In case it’s not immediately clear why, pop culture gatekeepers’ dogged determination in making sure that one sex is always portrayed as higher status than the other, is not exactly a good basis upon which to discuss a more egalitarian division of home responsibilities. A clear commitment by policymakers to do away with this practice then, would surely be helpful. Likewise, and finally, also a commitment to use gender neutral terms concerning childcare and housework standard practice for all government departments’ communications with the public. Because again, what possible harm could it do?

Source: YouTube.

Source: YouTube.

I’ve written about this before, most recently in 2019 about a new term for stroller that removes the notion that it’s a mother that should be pushing it. Sadly however, I’ve yet to encounter that new term personally, as An Hyae-min also laments in their April 24 “Mabu News” column for SBS News. Some excerpts to finish with:

우리나라의 성차별 언어는 얼마나 될까요? 한국어는 독일어와 프랑스어처럼 성별이 박혀있는 언어보다는 상대적으로 성중립적이기 쉬운 언어 구조를 가지고 있습니다. 하지만 그럼에도 불구하고 한국어 곳곳에서 성차별적 언어를 어렵지 않게 발견할 수 있어요. 2018년 여성가족부가 조사한 <일상 속 성차별 언어 표현 현황 연구> 결과를 보면, 성차별 언어 표현을 한 번이라도 접해본 사람의 비율은 응답자의 90%가 넘는 수치를 기록했습니다. 특히 성역할에 관한 차별 표현이 91.1%로 가장 많았어요. 여성을 지칭할 때만 ‘여’ 자를 따로 붙이는 ‘여배우’, ‘여의사’, ‘여경’ 같은 단어들이 그런 예가 되겠죠.

“How sexist is the Korean language? Actually, Korean tends to be relatively gender-neutral compared to gender-studded languages like German and French. Yet despite this, you can easily find many sexist terms in Korean. According to the results of a study conducted by the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family in 2018 on the status of sexist language expression in daily life, the proportion of people who have encountered sexist language at least once a day was recorded by more than 90% of the respondents. In particular, the expression of discrimination regarding gender roles was the highest at 91.1%. Examples of such words would be ‘actress’, ‘female doctor’, and ‘female police officer’, where the reference to the person’s sex is used only when referring to women who perform those roles [not the ‘default’ of men who do].” (Source, right: Geoffrey Fairchild; CC BY 2.0)

“How sexist is the Korean language? Actually, Korean tends to be relatively gender-neutral compared to gender-studded languages like German and French. Yet despite this, you can easily find many sexist terms in Korean. According to the results of a study conducted by the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family in 2018 on the status of sexist language expression in daily life, the proportion of people who have encountered sexist language at least once a day was recorded by more than 90% of the respondents. In particular, the expression of discrimination regarding gender roles was the highest at 91.1%. Examples of such words would be ‘actress’, ‘female doctor’, and ‘female police officer’, where the reference to the person’s sex is used only when referring to women who perform those roles [not the ‘default’ of men who do].” (Source, right: Geoffrey Fairchild; CC BY 2.0)

가족 호칭에서도 남편 쪽의 친척에게는 ‘도련님’, ‘아가씨’로 높여 부르지만 아내 쪽은 ‘처남’, ‘처제’로 부르고 있죠. 남성과 여성을 병렬적으로 배치할 경우에 ‘남녀노소’, ‘아들딸’, ‘남녀공학’ 등 남성이 먼저 위치하지만 비하하는 표현을 사용할 땐 ‘연놈’과 같이 여성을 지칭하는 말이 먼저 오기도 하고요. 심지어 여성이 앞에 와 있는 Ladies and Gentlemen을 ‘신사숙녀 여러분’으로 뒤바꿔 번역하기도 하죠.

“Even in family titles, relatives on the husband’s side are called ‘bachelor’ and ‘agassi/unmarried woman‘, but on the wife’s side they are called ‘brother-in-law’ and ‘sister-in-law’. Also, when men and women are placed in parallel in a neutral term, men are mentioned first, such as in ‘man and woman’, ‘son and daughter’, and ‘co-education’—even the English ‘Ladies and Gentlemen’ is reversed in Korean. But when using derogatory combined expressions, words referring to the women come first, such as in ‘Yeonnom.'”

● 유모차 → 유아차

: 여성(母)만 포함되어있는 단어로 평등육아 개념과 맞지 않음. 아이가 중심이 되는 유아차가 성중립 언어라고 할 수 있음.

● 스포츠맨십 → 스포츠정신

: 스포츠를 하는 누구나 가져야 하는 스포츠정신에 남성(man)만 포함되어있는 단어는 성평등에 어긋남.

● 자매결연 → 상호결연

: 상호 간의 관계 형성의 사회적 의미를 ‘자매’라는 여성적 관계로 표현. 여성에 대한 인격적 편향성을 높일 수 있다는 점에서 차별적 표현

● Stroller → Baby Car: A word that contains only women (母) does not fit the concept of equal parenting. A child-centered infant car can be said to be a gender-neutral language.

● Sportsmanship → Sports spirit : A word that contains only men in the spirit of sports that everyone who plays sports should have is against gender equality.

● Sisterhood relationship → Mutual relationship : Expressing the social meaning of mutual relationship formation as a feminine relationship called ‘sister’. Discriminatory expression in that it can increase personal bias toward women

이러한 성차별적 표현을 바꾸기 위한 노력은 곳곳에서 보입니다. 위에 정리해 둔 건 서울시 여성가족재단에서 2018년부터 진행하고 있는 성평등 언어 사전의 일부 내용들이에요. 서울시에선 시민들과 함께 성중립 언어 개선안을 만들어서 공표하고 있죠. 국립국어원에서는 가족 호칭에 대해서 아내 쪽 친척을 남편 쪽 친척의 호칭처럼 ~님으로 부르는 방식을 권고하기도 했어요.

“Efforts to change these sexist expressions are everywhere. Listed above are some of the contents of the Gender Equality Language Dictionary, which the Seoul Gender Equality and Family Foundation has been running since 2018. The Seoul Metropolitan Government is working with citizens to create and announce a gender-neutral language improvement plan. The National Institute of the Korean Language also recommended that relatives on the wife’s side be called with the honorific ‘nim’, just like relatives on the husband’s side.”

가장 보수적인 언어가 통용되는 법령 용어에서도 성차별적 언어 표현을 성중립 언어로 대체하고 있습니다. 법 조문에는 여전히 ‘미망인’과 같이 성차별적 표현이 있거든요. 이를 바꿔보려고 한국법제연구원이 법률을 전수 조사해서 차별 언어를 검토하기도 했습니다. 지난달엔 법무부 디지털 성범죄 전문위원회에서 ‘성적 수치심’이라는 단어를 성 중립적 용어로 변경하라고 권고한 일도 있었고요.

“Even in statutory terminology, which is used in the most conservative languages, sexist language is being replaced by gender-neutral language. There are still sexist expressions such as ‘widow’ in the law. To change this, the Korea Legislative Research Institute conducted a full investigation of the law to examine the language of discrimination. Last month, the Ministry of Justice’s Digital Sex Crimes Committee recommended that the word ‘sexual shame’ be changed to a gender-neutral term.”

Korean Sociological Image #61: Stereotypical Gender Roles in Pororo

Korean Sociological Image #61: Stereotypical Gender Roles in Pororo

RELATED POSTS

- The Hidden Roots of Korea’s Gender Wars

- Korean Sociological Image #89: On Getting Knocked up in South Korea

- The Korean Word for “Stroller” is Literally “Milk-MOTHER-Vehicle.” Let’s Start Using This New Term That Includes Fathers Too.

- Korean Sociological Image #78: Multicultural Families in Korean Textbooks

- Korean Sociological Image #59: Childcare is (Still) Women’s Job!

- “Single Mothers are Ignorant Whores”: Update

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)