Okay, this is far too long and honest, damnit.

Estimated reading time: 12 minutes. Image by Riki Ramdani at Unsplash (account since discontinued).

Estimated reading time: 12 minutes. Image by Riki Ramdani at Unsplash (account since discontinued).

Sorry for being so inconsistent with my posting schedule.

That’s about to change, big-time.

In three months from today, I’ll be bringing the blog to a close on WordPress, then continuing it on Substack, or on another, more ethical newsletter platform like it. Or in other words, all my preexisting posts will remain here, and remain freely available to read, but all my new posts will exclusively be published on Substack from then on.

At first, all those new posts will also be freely available to read. But later, sometime in the next three months after making the move, most of them, or at least the full versions of them, will only be available to paying subscribers, for somewhere between $2-$5 a month.

Well, that was the plan. Turns out, Korean internet banking restrictions considerably complicate getting donations for work published on non-Korean platforms. But I’ll work it out by March 8 (probably an overseas bank account will be required). And, whatever platform I do settle on, crucially all the new content will only be about the price of a cup of coffee. For a whole month.

So, I like to think that many of you won’t need to think twice about signing up when the time comes. Still, to help even further persuade you, the delay is only because over the next three months I’ll be making all the lifestyle changes and sacrifices necessary for me to begin delivering content to you regularly.

Starting by typing this with a broken finger!

How regularly you callously ask, indifferent to my pain? Well, I can’t make any promises at this stage, as this is only the first day of seeing what I’m capable of. But I can guarantee that once you get used to regular, much more frequent posts, you will genuinely miss them one they’re no longer available for free.

Here, the old me would start talking about the myriad of reasons for making the move, including the problems with the old tagline of “Korean Feminism, Sexuality, and Popular Culture.” But really, most would only be of interest to aging bloggers. So I’ll confine myself to just two, bumped to the end because they’re both a little disheartening, frankly.

Better to lead with the positive—my new tagline. Which a lot of thought went into, and which I’m very excited and passionate about focusing on in 2024—the year this Dragon comes into his element. But what do I mean by it exactly?

First, the “Sex,” short for “A Feminist Take on Korean Sexuality” (but which just didn’t have the same bite, you know?), will be the least changed from before. The only difference will be that there will be many more posts on that from now on, prompted by a dire need to reexamine and update the many aspects of it that I haven’t covered in many years. Some, in over a decade.

I have good excuses for that inattention. Compared to a decade or even just five years ago, the quality of instant translation programs, and of English-language reporting about Korea in general, have improved dramatically. When I have wanted to make another deep dive into any Korean-language sources on sexuality then, it’s seemed almost pointless when any non-Korean speaker can get their gist with just a mouseclick. (Albeit with some Korean ability still necessary to find the mistakes, sentences the program inexplicably missed, and so on.)

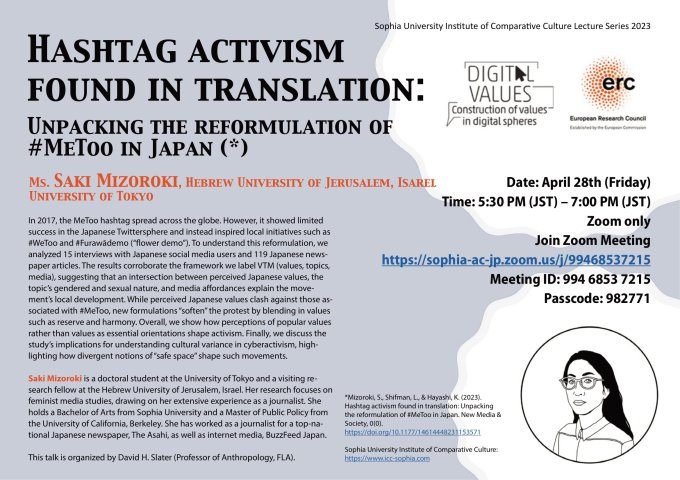

And yet, despite so much about Korean sexuality having changed in that time, and despite it being a more fascinating, contemporary, and relevant subject than ever, I’m just not seeing the attention I would have expected. Beyond academia, English-language coverage seems overwhelmed by Me-too, molka, and the ongoing legal limbo of abortion. All vitally important issues for sure, but hardly the entirety of what’s been going on.

So, because I really have always seen it as part of my mission to make factual information about Korean sexuality—not rumors and stereotypes from K-dramas and dating TikToks—available to international audiences, it’s high time for someone to step up and fill in those gaps. Again.

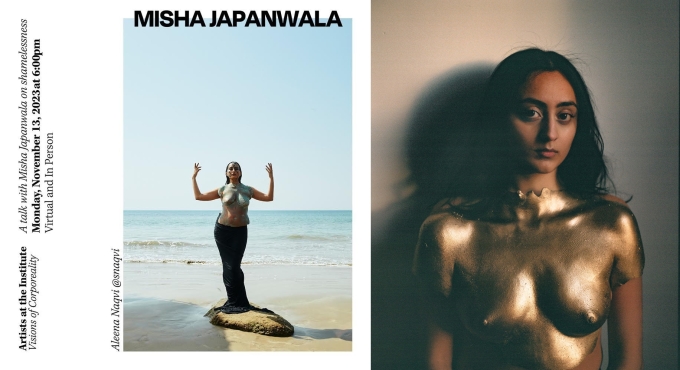

Next, “Sass” will be the biggest change. Partially, it’s to counter valid criticisms that I focus too much on negative news stories sometimes, which can be a downer for me to write just as much as they can be for you to read. But more, I’m emphasizing it because by this, the week of my first divorce-anniversary (divorcary?), I’m freer than ever before, and like to think I’m even acquiring some semblance of a social life too. Put all that together, and I have much more of a capacity and desire to meet and write about cool, sassy people who share my convictions, who are working hard for the many social changes needed in Korea (especially those related to sexuality), who inspire others to do so, and who very much deserve absolutely all the publicity and support they can get.

(Also, I’m finally realizing how many such people are right here in Busan, a much-neglected population compared to Seoulites. So, sorry not sorry for what will may be a local bias!)

Finally, there’s “Sensibility.” Which, not going to lie, I hope that mention alone will endear me to the huge, 99% overlapping demographic of feminists who are also Jane Austen fans, thereby instantly conveying my feminist credentials/allyship (take your pick! It’s all good!) despite the lack of an obvious place to insert “Feminism” or “Feminist” in the tagline. (Believe me, I tried!)

If not, then I could take a photo of my eight books by or about Jane Austen—but won’t, because no-one needs to know that three of those are actually three separate copies of Sense and Sensibility. Instead, let me offer the screenshot below, of me recently explaining “The Darcy Moment” to some sadly deprived female members of my bookclub (you know it’s me, because it’s a pink phone case). So we’re good?

But of course, there’s much more to it than that (I’ve even read some of those eight books!). Google “sensibility,” and even the most diehard Austen fan will have to admit it turns out to be extremely vague, with multiple definitions, especially when applied outside of an Austenian context. I’ve no qualms at all then, in appropriating the term to mean things which bring me joy, which resonate with me, which appeal to my sensibility then, and which I share because I hope—nay, fully expect—you’ll feel the same way about them too.

But of course, there’s much more to it than that (I’ve even read some of those eight books!). Google “sensibility,” and even the most diehard Austen fan will have to admit it turns out to be extremely vague, with multiple definitions, especially when applied outside of an Austenian context. I’ve no qualms at all then, in appropriating the term to mean things which bring me joy, which resonate with me, which appeal to my sensibility then, and which I share because I hope—nay, fully expect—you’ll feel the same way about them too.

Generally, there’ll be four kinds of them.

First, those about books (etc.) which may not even mention Korea, but will be about sexuality, feminism, and so on. Shared because they have such eye-opening lessons about and/or parallels to Korea, that not covering them because they’re not technically Korea-related would do every reader a grave disservice. Not to mention withholding an aspect of my life I’m extremely passionate about, am still searching for people in real life who feel the same way, and, if I couldn’t share it at least in writing, simply don’t know what I would do with myself. (Kill myself, I helpfully suggested in another recent bookclub meeting.)

A good example of this is what An Intimate Affair: Women, Lingerie, and Sexuality by Jill Fields (2007) revealed about the uncanny parallels between the corset industry in ‘Western’ countries—for want of a better term—in the 1920s and the “V-line” and “S-line” and other “bodyline” trends of the beauty industry in Korea 2000s-2010s, which have enmeshed themselves into Korean beauty ideals so successfully (see below) that they go almost completely unremarked upon today. All of a sudden while reading that book, how and why finally made sense.

And understanding is happiness.

Dat name.

Dat name.

Next, there’s similar epiphanies to share even if there’s no link to Korea whatsoever. Like what I learned recently about how stereotypes about ‘appropriate’ gender roles and slight, natural biological sex differences in various abilities end up magnifying and perpetuating them, and how in practice many of them are easily overcome with just a little training, no matter how much they may or may not be ‘hardwired.’ Because remember my post on that, in which I describe how what I read in one book led to what I’d read in another, to another book, to another article, and to another book I’d read nearly 30 years ago, and upended beliefs I’ve held dearly for nearly as long? Originally that was supposed to be just a quick quote, posted only to sound smart. Instead, I just couldn’t pretend I wasn’t making the connections as I typed the quote out. Connections I felt were absolutely necessary to do the original topic justice, but which also required a lot of time and effort to fully explore, let alone explain.

That’s why so many of my posts end up so long, and why my posting is so irregular.

Because I do, absolutely, want to give the deep dives people have said they prefer. But they’re just so exhausting, and just take so much time.

That said, they absolutely will keep coming. For maybe I’ve finally read enough books to reach some sort of tipping point? Because while writing that post, I reveled in my ability to make those connections just as much as I did from learning from them. And coincidentally, not long after, someone who knows me well, whose own special ability is recognizing the qualities and uniqueness of others, and who’s really adept at working with her knowledge of those to bring people together and pull off numerous successful meetings, clubs, and group events, made the same observation about me. Ergo, for the first time ever, at the tender age of 47, someone else noticed I was good at something I alone have also long thought I was good at.

Perhaps only now because, finally, I know I’m good at it.

So what then, if those connections I make aren’t always about Korea?

Third, there’s Korean popular culture. But almost always though, absolutely not mainstream movies, dramas, or K-pop. For various reasons, those have generally never appealed to me over the last ten years or so, and besides which they get more than enough coverage elsewhere. Instead, I want to share moments like when I went to see After Me Too last October, which I frankly attended more out of a sense of obligation than anything else, wanting to show my support but also expecting to find it dry and political, and that I would struggle with the Korean.

Third, there’s Korean popular culture. But almost always though, absolutely not mainstream movies, dramas, or K-pop. For various reasons, those have generally never appealed to me over the last ten years or so, and besides which they get more than enough coverage elsewhere. Instead, I want to share moments like when I went to see After Me Too last October, which I frankly attended more out of a sense of obligation than anything else, wanting to show my support but also expecting to find it dry and political, and that I would struggle with the Korean.

What actually happened though, was that I understood far more than I thought, and found the film surprisingly moving. And it sparked an interest in films like it I’ve ironically barely covered at all here.

I was still so reticent though, because if I had shared that reaction here, readers might have just been left frustrated with how practically difficult or even impossible it would have been to see the film for themselves. But then, not sharing would hardly help rectify that situation, yes? And films do sometimes get shown again, if you know where to look. Just knowing about how good one was then, even if you missed it, helps you keep an eye out for others coming up by the same directors and/or featuring the same actors. Extend the same logic to other much neglected, indie films. To all the female-centered Korean short films I’ve been watching on Purplay with a vengeance since that moment of mine in the empty theater last year. To the Korean-language books I’ve read. To the feminist dances. All links which are just a drop in the ocean compared to what I want to experience, have experienced, and, despite everything I’ve just said, am wondering what on Earth was stopping me from sharing previously.

Finally, if you’re reading this far, it’s safe to assume we likely share many of same interests—and the same needs to delve into things completely unrelated to Korea sometimes, or even any of all the other things mentioned so far. So—yeah, it’s not just you detecting a theme here—why not talk about those too?

Finally, if you’re reading this far, it’s safe to assume we likely share many of same interests—and the same needs to delve into things completely unrelated to Korea sometimes, or even any of all the other things mentioned so far. So—yeah, it’s not just you detecting a theme here—why not talk about those too?

But with sooo much to talk about, and so much passion to do so, and desire to be heard, that begs the question of why I’ll be limiting myself to only doing so with paid subscribers eventually. Which brings me to conclude here with those two, disheartening reasons I alluded to for making that change.

First, because other than a small flurry of one-time donations when I wrote about blogging in June 2021, for several years before and since then I’ve only had one regular donor, who donates $2 a month. While I’ll always be eternally grateful to her (I love you MT!), that there’s only her after 16 years of blogging just underscores how long overdue a move to paid subscriptions really is, and how ridiculous it is that even now, I’m not fully making the leap for another six months.

Next, although I have over 10,000 followers between all my social media and email subscribers, in the last five years say, I’ve probably only ever interacted with less than 50 of you, and only a dozen or so often enough to know your names. Add that almost no-one leaves comments on blogs themselves these days, then the reality is that writing here is a pretty lonely and isolating experience most of the time. Much more so than I think most readers realize.

By saying that, I absolutely don’t want anyone to feel guilty for not engaging with my content in the past, nor that future paying subscribers should at all feel obliged to. It’s completely my own choice to write at home alone, instead of doing something more sociable. But, having made that choice, which presumably you’d like me to continue making…it’s just hard sometimes, you know? The utter silence I usually receive in response to most posts, even after spending weeks pouring my heart and soul into some of them, can feel heartbreaking sometimes. Like I’m just screaming into the void.

Put all those reasons together, then I’d much rather have just ten people who are inclined to say hi sometimes, or who at least show they value my work through their renewed subscriptions, than 10,000 who don’t think I’m worth even a cup of coffee.

(More than ten people would be nice too though!)

And with that, to those of you who do want to say hi, let’s get to work on finally building our community, which I will do with my best attempts to keep you entertained, interested, and informed as I can.

So I’ll see you again very soon!

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)

Estimated reading time: 2 minutes.

Estimated reading time: 2 minutes.