Don’t let my glorious laser tits deter you from an eye-opening interview, and a must-read!

Estimated reading time: 11 minutes.

Estimated reading time: 11 minutes.

First, a quick update to explain my absence this past month,

Basically, I’ve finally gotten my shit together.

I could count the ways. Instead, suffice to say I’m so enthused and energized that I’ve even started paying attention to my laser tits again.

You read that right. (You’ll thank me for passing on this “꿀팁” later.) Ten random notifications from a reminder app a day, I advise, is the sweet spot for perking you up before starting to get annoying:

Naturally then, life chose to reward my newfound drive by bookending those past four weeks with two debilitating colds. Repetitive strain injury has flared up in my right arm too,* leaving me in agony every time I want to do anything even remotely fun or pleasurable with my hand. Like, say, eating or sleeping (what did you think I meant?), let alone banging away at a keyboard.

Naturally then, life chose to reward my newfound drive by bookending those past four weeks with two debilitating colds. Repetitive strain injury has flared up in my right arm too,* leaving me in agony every time I want to do anything even remotely fun or pleasurable with my hand. Like, say, eating or sleeping (what did you think I meant?), let alone banging away at a keyboard.

With my resolve being so sorely tested, literally, my response is to push even harder through my huge backlog of writing, as well as my new plans to completely overhaul this blog and my social media use. What those plans actually are, I’m going to tend towards doing before explaining. But one I already announced back in October—more geeking out over things that bring me joy, no matter how obscure or academic. The difference now being, I realize life is just too short to worry about losing followers who don’t share my obscure passions, or curious, ribald sense of humor.

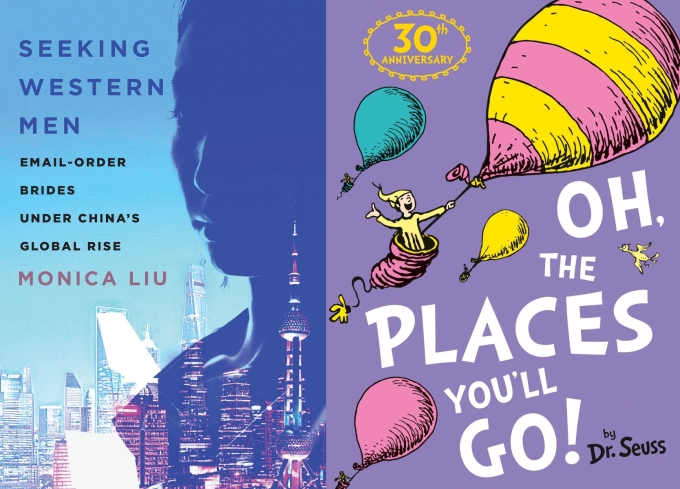

On that note, the New Book Network’s (NBN) recent podcast interview of Monica Liu, about her new book Seeking Western Men: Email-Order Brides Under China’s Global Rise (2022), is conspicuously bereft of laser tits, but is no less jaw-dropping for all that. Primarily, for Liu’s emphasis on the women’s perspectives and their sense of agency, which in hindsight I’ve much neglected in my own coverage of migrant brides to Korea over the years (understandably, given how so many are exploited and abused, but a neglect nonetheless). Moreover, despite the title of the book, and NBN’s synopsis below, it quickly becomes clear while listening to the interview that Chinese seekers of marriage with Western men share many of the same issues and goals with those Chinese, Central Asian, Russian, and Southeast Asian women seeking Korean men.

Her study of China’s email-order bride industry offers stories of Chinese women who are primarily middle-aged, divorced, and proactively seeking spouses to fulfill their material and sexual needs. What they seek in their Western partners is tied to what they believe they’ve lost in the shifting global economy around them. Ranging from multimillionaire entrepreneurs or ex-wives and mistresses of wealthy Chinese businessmen, to contingent sector workers and struggling single mothers, these women, along with their translators and potential husbands from the US, Canada, and Australia, make up the actors in this multifaceted story. Set against the backdrop of China’s global economic ascendance and a relative decline of the West, this book asks: How does this reshape Chinese women’s perception of Western masculinity? Through the unique window of global internet dating, this book reveals the shifting relationships of race, class, gender, sex, and intimacy across borders.

I strongly recommend listening to the interview yourself; at 39 minutes long, it doesn’t at all drag on like, frankly, most other NBN interviews do. To encourage you to do so, here are several eye-opening excerpts, all lovingly, painstakingly transcribed by myself (my apologies for any minor errors).

(Too young, and too well-off?) Photo by bruce mars on Unsplash.

(Too young, and too well-off?) Photo by bruce mars on Unsplash.

First, from 7:30-8:45, an important difference between Chinese women seeking Western men to migrant brides in Korea: the former tend to be much older and financially well-off. As we’ll see soon, this has big implications for the power dynamics between prospective partners:

Q) Why really did the Chinese women seek Western men?

A) For a couple of different reasons. Across the board, one main reason I saw was that the women felt aged out of their local dating market, because men of similar age and economic standing tended to prefer much younger, never-married women without children, and so women believed Western men were more open to dating women their age. And there’s also some differences based on the women’s socioeconomic class. A lot of women who are financially well-off have previously been married to very wealthy Chinese men that cheated on them and left them for younger women, and so think that Western men are going to be more loyal and more family-orientated—that being the primary reason. While women who struggled financially, have often divorced Chinese ex-husbands that lost their jobs and couldn’t support their families, and so these women are also seeking financial stability in their new marriages. Finally, there’s also a group of women who wish to send their kids to college in the US, to escape the very, very brutal college entrance exam in China, but they couldn’t do that as single moms that were financially struggling.

Next, from 10:20-11:20, on how Chinese dating marriage agencies both respond to and perpetuate Occidental stereotypes:

Q) Tell us about global financial crisis of 2008 when the men lost their jobs. Did this impact the dating scene?

A) Yes, this certainly impacted the dating scene. At the dating agencies, before the crisis there would be this idea that many of the men would possibly be financially well-off, but actually after the crisis a lot of women were actually discovering off-site that those men that they thought were financially well-off were not in that position, and as a result one of the tactics that the agencies used to promote these men to the women was that these men were loyal, devoted, and family-oriented, and thereby worth of marriage, even if they’re not particularly financially well-off.

Photo by Marcelo Matarazzo on Unsplash.

Photo by Marcelo Matarazzo on Unsplash.

Then from 13:28-15:11, on the racial hierarchies contained within those Occidental stereotypes. But already, Chinese women’s agency is evident in their readiness to reject or subvert these:

Q) You talked about the discrimination against Black men with the Chinese women, but not other racial groups. Tell us more.

A) When I stepped into the dating agency, I found that Chinese women were very reluctant to date Black men. And for that reason, the agencies actually had a policy to not entertain emails from Black men unless given special permission from the women, in order not to “offend” the women. I’m not exactly sure what their personal reasons were…but I do know China has a long-standing history of anti-Black prejudice where Blacks are stereotyped as savage, hypersexual, and violent.

However, the women didn’t seem to discriminate against other racial groups, and to them, interestingly, the term “Westerner” included not only Caucasians but also Latinos and Native Americans. And occasionally some women would actually refer to Western men of Northern- or Central-European ancestry as “pure white,” and Latin-American men, or men of South-European ancestry, for example Italian men, or Native American men, as “non-pure white.” However, being pure white didn’t seem to actually boost the men’s desirability in the women’s eyes, and in fact I saw that some women in fact preferred the non-pure white look and they found the darker hair and eye color to be more Asian-looking, and more familiar and more pleasing to their eye than someone who is, say, blond-haired and blue-eyed.

Photo by Roselyn Tirado on Unsplash.

Photo by Roselyn Tirado on Unsplash.

From 18:24-19:52, on the traditional, patriarchal values the Western men using international dating agencies often bring to their anticipated relationships with Chinese women. Obviously, by no means all (or even a majority) do. But just as obviously, it’s surely no coincidence that many Korean men do the same:

Q) Now give us the profile of the Western male seeking a Chinese woman.

A) The majority of the men enrolled tended to be older, divorced, and tend to come from lower-middle class or working class backgrounds, although some were middle class. I’ve seen a lot of truck drivers, lots of small business owners, and these men tend to feel left behind by globalization as agriculture, manufacturing, and small businesses started declining. So these men actually viewed this changing economic landscape as a threat to their masculinity.

Now a lot of sociologists’ studies show that marriage rates have declined among working class men, and poor men, because women within their own class find them to be too poor to be marriage worthy. So for these men, having slipped down the socioeconomic ladder, they really struggle to hold on to what privilege they have left by pursuing so-called “traditional” marriages, possibly with foreign brides, because they think this will allow them to exert some kind of dominance and control at home. And there’s also some middle class men who, despite being financially stable, they still feel left out of place within the new gender norms that have emerged in Western societies, [supposedly] dominated by feminists who they see as destroying the family and nation through their spoiled behavior and materialism.

Photo by Conikal on Unsplash.

Photo by Conikal on Unsplash.

And, reluctantly, a final excerpt from 23:21-25:10 (there were so many I wanted to highlight!), on the upending of global masculinity and racial ideals when women are empowered to reject those marriages:

Q) Let’s look now at some of the theories about Western masculinity. What did you find concerning race, class, gender, globalization, and migration?

A) First, I challenge readers to rethink the relationship between race and class…the question I ask is, does Western masculinity still command some degree of hegemonic power in China, despite China’s global rise—and I confirm that it does, by showing how Chinese dating agencies market their Western male clients as morally superior to Chinese men despite their lack or wealth. So the fact is that this portrayal still sells in China, and this reflects this continued superiority of Western culture within the Chinese women’s imagination.

However, in this book I also show a lot of moments when Western masculinity is starting to lose its hegemonic power, and this typically happens in the latter stages of the courtship process, when couples go offline and start meeting face-to-face. And in this book, I show how some of these women quickly rejected their working class, Western suitors, once they realized these men didn’t embody the type of elite masculinity that they were seeking in a partner, and instead these women would choose to continue having affairs with their local Chinese lovers, even if those men were married and not willing to leave their wives. And this is because [they] had these refined tastes, lifestyles, and sexual know-hows that a lot of their foreign suitors lacked.

Two final points of interest to round off. First, by coincidence, shortly after listening to this interview I got an alert that Kelsey the Korean was busy dismantling Western masculinity’s hegemonic power in Korea too:

Next, another well-timed coincidence: the latest issue of the Korean Anthropology Review just dropped, with an article by Han Seung-mi—”Critique of Korean Multiculturalism as Viewed through Gendered Transnational Migration in Asia: The Case of Vietnamese Returnee Marriage Migrants“—that sounds perfectly placed to challenge my own image of migrant brides in Korea as passive victims (my emphasis):

This article analyzes “returnees from marriage migration” by focusing on Vietnamese women from Cần Thơ and Hai Phong who have been to South Korea for marriage migration. In contrast to prevalent concerns in South Korea about the possibility of “child abduction” by Vietnamese mothers/divorcees, the author found many “deserted” Korean Vietnamese children and their mothers in Vietnam through this research. There is also a growing number of Vietnamese “return marriage migrants,” women who came back to South Korea after their first divorce and return to Vietnam. The article emphasizes the complexities and multidirectional trajectories of marriage migration and highlights the agency of female migrants, whose contribution to family welfare and to “development” is often overshadowed by their status within the family.

Does it really matter that, technically, my copy of the book hasn’t actually arrived yet? If you’ve read this far, I hope you too will indulge yourself (38,170 won on Aladin!), and I look forward to hearing your thoughts.

*I first had repetitive strain injury about 10 years ago, consequence of having my keyboard too close to me, forcing me to bend my arms to type; fortunately, it resolved itself in a few weeks once I moved my computer just shy of arm’s length. This time round, it’s undoubtedly due to spending hours in bed on my phone, again bending my arms to use it; now that I’ve stopped, hopefully again the pain will go away just as quickly.

In the meantime, I can’t stress enough how much my arm can hurt at the moment, nor how debilitating it is to be literally too scared to use your right hand as a result. So, if you reading this, please do take a moment to consider how you physically use your devices, and for how long!

Related Posts:

- Manufacturing Consent?: Socializing Migrant Brides to Korea into Becoming Docile, Obedient ‘Baby-Making Machines’

- Korean Textbooks for Foreign Brides Teach How to Survive the Patriarchy

- Korean Sociological Image #78: Multicultural Families in Korean Textbooks

- “With Throbbing Heart and Trembling Hands, the Groom Undresses the Waiting Bride, to Unveil the Mystery”

- Why Women Pay More to Join Korean Marriage Agencies

- Korean Sociological Image #89: On Getting Knocked up in South Korea

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)