Source, edited

Source, edited

Yes, I know. Korean bodylines again. Surely, I really do have some kind of fetishistic obsession with them, as my trolls have long maintained.

Perhaps. Mainly, it’s because I’ve been very busy giving this presentation about them at Korean universities these past two months. Even, I’m very happy to report, getting invited back to some, and finally—squee!—making a small profit too. S-lines, I guess, are now very much my thing.

Instead of feeling top of my game though, frankly I’m wracked by self-doubt. I constantly worry about coming across a real fashion-history expert in the audience, who will quickly reveal me to be the rank amateur I really am.

Source: Heal Yourself, Skeletor

Source: Heal Yourself, Skeletor

So, to forestall that day for as long as possible, here is the first of many posts this summer correcting mistakes in my presentation I’ve found, and/or adding new things I’ve learned. But first, because it’s actually been over a year since I last wrote on this topic, let me remind you of the gist:

1) Korea’s “alphabetization” (bodylines) craze of the mid-2000s has strong parallels in the rationalization of the corset industry in Western countries in the 1910s to 1940s.

2) Fashion and—supposedly immutable and timeless—beauty ideals for women change rapidly when women suddenly enter the workforce in large numbers, and/or increasingly compete with men. World War Two and the 1970s-80s are examples of both in Western countries; 2002 to today, an example of the latter in Korea.

3) With the exception of World War Two though, when the reasons for the changes were explicit, correlation doesn’t imply causation. Noting that bodylines happened to appear during a time of rapid economic change in Korea does not explain why they came about.

Maybe, simply because there’s nothing more to explain, and we should be wary of assuming some vast patriarchal conspiracy to fill the gap, and/or projecting the arguments of Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth (1990) and Susan Faludi’s Backlash (1991) to Korea. Indeed, arguably it’s mostly increased competition since the Asian Financial Crisis that has profoundly affected the demands on job-seekers’ appearances, of both sexes. Also, the financial demands of the K-pop industry go a long way towards explaining the increased sexual objectification in the media in the past decade.

Which brings me to today’s look at the evolving meaning of “glamour” in American English, which I use to illustrate the speed of those changes in World War Two:

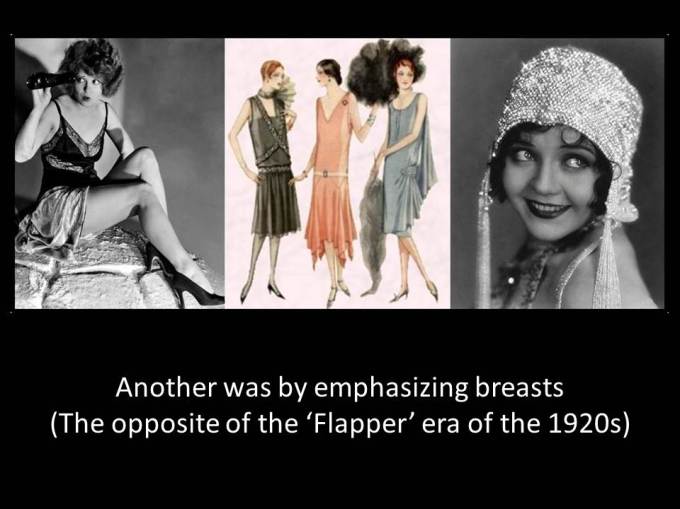

These are necessary generalizations of course, whereas the reality was that contradictory and competing trends coexisted simultaneously, which you can read about in much greater depth back in Part 4. But this next slide was just plain wrong:

These are necessary generalizations of course, whereas the reality was that contradictory and competing trends coexisted simultaneously, which you can read about in much greater depth back in Part 4. But this next slide was just plain wrong: With that slide, I went on to give a few more examples to demonstrate how glamour, then meaning large breasts, soon came to mean just about anything. But then I read Glamour: Women, History, Feminism by Carol Dyhouse (2010), and discovered that the word has always been very vague and malleable (albeit still always meaning bewitching and alluring). Moreover, to my surprise, “breasts”—the first thing I look for in new books these days—weren’t even mentioned in the index. Nor for that matter, “glamour” in Breasts: A Natural and Unnatural History by Florence Williams (2013) either. Given everything I’ve said and written about them, I feel they deserved more attention that that (although Dyhouse does cover them in the chapter “Princesses, Tarts, and Cheesecake” somewhat), but certainly there was only ever a strong association with glamour at best. Also, my timing was wrong, for that association began as early as the late-1920s, and didn’t peak until after the war. (See the introduction or from page 134 of the dissertation Hollywood Glamour: Sex, Power, and Photography, 1925–1939, by Liz Willis-Tropea, 2008.)

With that slide, I went on to give a few more examples to demonstrate how glamour, then meaning large breasts, soon came to mean just about anything. But then I read Glamour: Women, History, Feminism by Carol Dyhouse (2010), and discovered that the word has always been very vague and malleable (albeit still always meaning bewitching and alluring). Moreover, to my surprise, “breasts”—the first thing I look for in new books these days—weren’t even mentioned in the index. Nor for that matter, “glamour” in Breasts: A Natural and Unnatural History by Florence Williams (2013) either. Given everything I’ve said and written about them, I feel they deserved more attention that that (although Dyhouse does cover them in the chapter “Princesses, Tarts, and Cheesecake” somewhat), but certainly there was only ever a strong association with glamour at best. Also, my timing was wrong, for that association began as early as the late-1920s, and didn’t peak until after the war. (See the introduction or from page 134 of the dissertation Hollywood Glamour: Sex, Power, and Photography, 1925–1939, by Liz Willis-Tropea, 2008.)

For instance, take this excerpt from Uplift: The Bra in America by Jane Farrell-Beck and Colleen Gau (2002, page 103; my emphasis):

The War Production Board severely restricted the use of chromium-plated wire for civilian-use products. Brassiere manufacturers improved fasteners, but renounced wiring. Besides, glamour was not what brassieres were about in 1941-45. Posture, health, fitness, and readiness for action constituted the only acceptable raisons d’être for undergarments-at-war, dubbed “Dutiful Brassieres” by the H & W Company.

Indeed, it turns out those lingerie ads in one of my slides come from 1948 and 1949 respectively (and I’ve no idea what that girdle ad was doing there!). And here’s another excerpt, from The Home Front and Beyond: American Women in the 1940s by Susan M. Hartmann (1983, page 198; my emphasis):

Women adapted their appearance to the wartime look, which deemphasized physical differences between the sexes, but they did not completely abandon adornments symbolizing femininity. While some adjusted to the disappearance of silk and nylon by going barelegged, others used leg makeup and some even painted on a seam line. Women emphasized their lips by favoring dark colors. The focus on breasts did not peak until later, but the sweatergirl look, popularized by Lana Turner and other movie stars, had its origins in the war years, and women competed in Sweater Girl contests as early as 1943.

In short, the trend is still there, and, “much of women’s social history [being] embedded in clothes, cosmetics, and material culture” (Dyhouse, p. 7.), remains fascinating for how, as a product of the era when cinema first began to have a profound impact on fashion, it set the standard of slim waists and large breasts that largely remains in Western—and global—culture today.

But covering all that in a stand-alone presentation, which I’ve really struggled to get down to an hour a half? In hindsight, it’s a poor, unnecessarily complicated choice to get my point about rapid change across.

Source: How do ya like me now?

Source: How do ya like me now?

Likely, I fixated on glamour because it’s where “Bagel Girl” (베이글녀) derives from, a Korean bodyline that’s been popular for about 4-5 years. A blatantly infantilizing and objectifying term, I was happy to read back in 2011 that Shin Se-kyung at least has rejected being labeled as such (alas, Hyoseong of Secret is quite happy with it), echoing Lana Turner’s distaste at being the first “Sweater Girl.”

Then I discovered the Bagel Girl had a precedent in the “Lolita Egg” (롤리타 에그) of 2003, which, as the following advertorial explains, likewise emphasized the childish features of female celebrities then in their early-20s—who would surely have preferred being better known as adults instead. While I genuinely despair that its authors and interviewees actually got paid for their work (you’ll soon see why!), it does demonstrate the remarkable historical continuity to medical discourses about “Western” and “Asian” women’s bodies, and of the incessant drive to infantilize their owners.

‘롤리타-에그’ 얼굴 뜬다…2000년대 미인은 ‘어린소녀+계란형’ The “Lolita Egg” Face …Beauties of the 2000s have ‘Young girl + Egg Shape’

‘롤리타-에그’ 얼굴 뜬다…2000년대 미인은 ‘어린소녀+계란형’ The “Lolita Egg” Face …Beauties of the 2000s have ‘Young girl + Egg Shape’

Donga Ilbo (via Naver), November 2, 2003

이승재기자 sjda@donga.com, 조경복기자 kathycho@donga.com / By Lee Sung-jae and Jo Gyeong-bok

‘롤리타-에그 (Lolita-Egg)’형 얼굴이 최근 뜨고 있다 The ‘Lolita Egg’ Face Trend Has Been Booming Recently

1990년대 성숙한 미인상으로 각광받던 ‘계란(Egg)’형 얼굴의 연장선상에 있으면서도, 길이가 짧은 콧등과 좁은 턱, 넓은 이마 등 어린 아이의 이미지로 ‘롤리타 콤플렉스’(어린 소녀에 대한 성적 충동·롤리타는 12세 소녀를 향한 중년 남자의 광적인 사랑을 담은 블라디미르 나보코프의 동명 소설에 등장하는 소녀 이름)를 자극하는 ‘이중적 얼굴’이 주목받고 있는 것.

While the 1990s trend for mature, beautiful women with egg-like faces continues, now it has combined with a short nose-bridge, narrow chin, and wide forehead, reminiscent of a child’s. This ‘double face’ stimulates the ‘Lolita Complex’, based on the Lolita novel by Vladimir Nabokov (1955), about a middle-aged man’s insane love and sexual urges for a 12 year-old girl of the same name.

Source

Source

‘롤리타-에그’형의 대표는 탤런트 송혜교(21)와 가수 이효리(24)다. 또 드라마 ‘선녀와 사기꾼’(SBS), ‘노란손수건’(KBS1)에 이어 SBS ‘때려’에 출연 중인 탤런트 소이현(19)과 영화 ‘최후에 만찬’에 비행(非行) 소녀 ‘재림’으로 나오는 신인 조윤희(21)도 닮은꼴이다.

Representative stars with the Lolita Egg face shape are talent Song Hye-Kyo (21; Western ages are given) and singer Lee Hyori (24). Other women that resemble them include: the drama talent So Yi-hyun (19), who has appeared in Fairy and Swindler (SBS), Yellow Handkerchief (KBS1), and is currently starring in Punch (SBS); and movie rookie Jo Yoon-hee (21), who played the character Jae-rim in The Last Supper (2003).

조용진 한서대 부설 얼굴연구소 소장은 “이 얼굴형은 자기중심적이면서도 콧대가 높지 않아 ‘만만한’ 여성상”이라며 “경제 불황이 장기화하면서 퇴폐적이면서 유아적인 여성상을 찾는 동시에 수렁에서 구원해 줄 강력하고 성숙한 여성상을 갈구하고 있다는 표시”라고 분석했다.

Jo Yong-jin, head of the Face Research Institute affiliated with Hanseo University, explained “While this face shape is self-centered, the nose bridge is not high, making it a manageable female symbol,” and that “While the recession prolongs, people long for a decadent but childlike female symbol, but at the same time also strongly long for a mature female symbol to save them from the depths.”

롤리타 에그’ 얼굴의 특징 Unique Points about the Lolita Egg Face

얼굴선은 갸름하지만 전체적으론 둥그스름하고 부드럽다. ‘롤리타 에그’형은 90년대 채시라와 최진실에서 보듯 갸름한 듯하면서도 약간 네모진 미인형에 비해 특징이 적다. ‘어디선가 본 듯한’ 느낌을 주어 대중성이 강하다.

The face-line is slender, but overall it is roundish and soft. As you can see from images of Chae Shi-ra and Choi Jin-sil, in the 1990s the Lolita Egg face shape  also looked slender, but compared to slightly square-faced beauties didn’t have many characteristics. It was massively popular, because it gave the feeling of a face you could see anywhere (source, right).

also looked slender, but compared to slightly square-faced beauties didn’t have many characteristics. It was massively popular, because it gave the feeling of a face you could see anywhere (source, right).

얼굴의 포인트는 코. 채시라 등의 코는 높으면서도 콧등이 긴데 반해 이 얼굴형은 콧등이 낮고 그 길이가 짧아 ‘콧대가 높다’는 느낌이 없다. 다만 코끝이 버선코 모양으로 솟아올라 비순각(鼻脣角·코끝과 인중 사이의 벌어진 정도·그림)이 90도 이상인 것이 특징. 코가 짧은 동양적 특징과 비순각이 큰 서양적 특징(한국인은 평균 90도가 채 못 되나 최근 120도까지 끌어올리는 성형수술이 유행이다)이 동시에 나타난다.

The point of the face is the nose. Compared with the cases of Chae Shi-ra and so on, whose noses are high and have long nose bridges, the nose bridge of a Lolita Egg face is low and short, so it doesn’t give the feeling of a high nose bridge. However, the tip of the Lolita Egg nose is marked for resembling the tip of a bi-son (a traditional women’s sock), soaring upward, and the philtrum is more than 90 degrees (see picture). A Lolita Egg face has a combination of this philtrum, which is a Western trait (Koreans typically have one less than 90 degrees; however, the trend in cosmetic surgery is to get one between 90 and 120 degrees) and a short nose, which is an Asian trait.

미고 성형외과 이강원 원장은 “다소 나이 들어 보이고 노동을 즐기지 않는 듯한 느낌을 주는 긴 코에 비해 짧고 오뚝한 코는 귀엽고 애교 있으며 아이 같은 이미지를 준다”고 말했다. 이런 코는 이미연의 두텁고 귀티 나는 코가 주는 ‘접근하기 어려운’ 느낌에 비해 ‘만인이 사랑할 수 있을 것 같은’ 느낌을 유발한다.

Migo Cosmetic Surgery Clinic head Won Chang-un said “A long nose gives an impression of age and that one doesn’t enjoy one’s work, whereas a short but high nose gives one of cuteness and aegyo. A thick but elegant nose like that of Lee Mi-yeon’s [James—below] gives a cold, stand-offish impression, but a Lolita Egg one gives off one that the woman can be loved by all.

Source

Source

턱은 앞으로 다소 돌출했지만 턱의 각도가 좁아 뾰족한 느낌도 든다. 이는 일본 여성의 얼굴에 많이 나타나는 특징. 28∼32개의 치아를 모두 담기엔 턱이 좁아 덧니가 있는 경우가 많다. 어금니가 상대적으로 약해 딱딱한 음식을 씹는 것에는 약한 편.

[However], while the jaw of the Lolita Egg protrudes forward, it is narrow, giving a pointy feeling. This is characteristic of many Japanese women [James—see #3 here]. But because 28-32 teeth are crammed into such narrow jaws, there are also many cases of snaggleteeth. The molars also tend to be weak, making it difficult to chew hard food.

눈과 눈썹은 끝이 살짝 치켜 올라가 90년 대 미인상과 유사하나, 눈의 모양은 다르다. 90년대 미인은 눈이 크면서도 가느다란 데 반해 이 얼굴형은 눈이 크고 동그래 눈동자가 완전 노출되는 것이 특징. 가느다란 눈에 비해 개방적이고 ‘성(性)을 알 것 같은’ 느낌을 준다.

The end of the eyes and eyebrows raise up slightly at the ends, resembling the style of 1990s beauties, but the shape is different. Compared to that large but slender style, the Lolita Egg eyes are rounder and more exposed. This gives a feeling of openness and greater sexual experience.

얼굴에 담긴 메시지 The Message in a Face

‘롤리타 에그’형의 여성들은 남성들의 ‘소유욕’을 자극하는 한편 여성들에게 ‘똑같이 되고 싶다’는 워너비(wannabe) 욕망을 갖게 한다. 예쁘면서도 도도한 인상을 주지 않아 많은 남성들이 따른다. 이로 인해 이런 여성들은 선택의 여지가 많아 독점적으로 상대를 고르는 듯한 인상을 주기도 한다.

On the one hand, the Lolita Egg stimulates men’s possessiveness, whereas to women it turns them into wannabees. It’s a pretty face shape, but doesn’t give off a haughty, arrogant impression, proving very popular with men. Women who have it can pick and choose from among their many male followers (source right: unknown).

On the one hand, the Lolita Egg stimulates men’s possessiveness, whereas to women it turns them into wannabees. It’s a pretty face shape, but doesn’t give off a haughty, arrogant impression, proving very popular with men. Women who have it can pick and choose from among their many male followers (source right: unknown).

인상전문가 주선희씨는 “낮은 코는 타협의 이미지를 주는 데 반해 선명한 입술 라인은 맺고 끊음이 분명한 이미지가 읽힌다”며 “이런 얼굴은 남성을 소유한 뒤 가차 없이 버릴 것 같은 느낌을 주기 때문에 여성들이 강한 대리만족을 얻게 된다”고 말했다.

Face-expression specialist Ju Seon-hee said “A low nose gives an impression that the owner will readily give-in and compromise, whereas the clear lipline of a Lolita Egg gives an image of decisiveness,” and that women with the latter can gain a strong sense of vicarious satisfaction through using (lit. possessing) and then discarding men.”

최근 인기 절정의 댄스곡인 이효리의 ‘10 Minutes’ 가사(나이트클럽에서 화장실에 간 여자 친구를 기다리는 남자를 유혹하는 내용)에서도 나타나듯 “겁먹지는 마. 너도 날 원해. 10분이면 돼”하고 욕망을 노골적으로 강력하게 드러내는 이미지라는 것이다.

Like the lyrics of Lee Hyori’s song 10 minutes say (about a woman who seduces a man at a nightclub while he is waiting for his girlfriend in the bathroom), currently at the height of its popularity, “Don’t be scared. You want me too. 10 minutes is all we need”, this a strong and nakedly desiring image. (End)

Source

Source

For more on the negative connotations of “Asian” bodily traits, perpetuated by cosmetic surgeons and the media, please see here (and don’t forget Lee Hyori’s Asian bottom!). As for the infantilization of women, let finish this post by passing on some observations by Dyhouse, from page 114 (source, right; emphasis):

Nabokov’s Lolita was published (in Paris) in 1955: the book caused great controversy and was banned in the USA and the UK until 1958. Baby Doll, the equally contentious film with a screenplay by Tennessee Williams, starring Carroll Baker in the role of its lubriciously regressive, thumbsucking heroine, appeared in 1956. The sexualisation of young girls in the  culture of the 1950s had complex roots, but was probably at least in part a male reaction to stereotypes of idealized, adult femininity. Little girls were less scary than adult women, especially when the latter looked like the elegant Barbara Goalen and wielded sharp-pointed parasols. Images of ‘baby dolls’ in short, flimsy nightdresses infantilized and grossly objectified women: they segued into the image of the 1960s ‘dolly bird’, undercutting any assertiveness associated with women’s role in the ‘youthquake’ of the decade.

culture of the 1950s had complex roots, but was probably at least in part a male reaction to stereotypes of idealized, adult femininity. Little girls were less scary than adult women, especially when the latter looked like the elegant Barbara Goalen and wielded sharp-pointed parasols. Images of ‘baby dolls’ in short, flimsy nightdresses infantilized and grossly objectified women: they segued into the image of the 1960s ‘dolly bird’, undercutting any assertiveness associated with women’s role in the ‘youthquake’ of the decade.

Did I say you shouldn’t project Western narratives onto Korea? I take that back. Because goddamn, would that explain a lot of things here!

Update: See here for a Prezi presentation on “Trends of beautiful faces In Korea.”

The Revealing the Korean Body Politic Series:

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic Part 12: If You Don’t Have Kim Yuna’s Vital Statistics, Your Body Sucks and You Will Totally Die Alone

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 11: 노출이 강간 유혹?…허튼소리 말라 Wearing Revealing Clothes Leads to Rape? Don’t Be Absurd

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 10: “An epic battle between feminism and deep-seated misogyny is underway in South Korea”

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 9: To Understand Modern Korean Misogyny, Look to the Modern Girls of the 1930s

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 8: The Bare-leg Bars of 1942

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 7: Keeping abreast of Korean bodylines

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 6: What is the REAL reason for the backlash?

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 5: Links

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 4: Girls are different from boys

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 3: Historical precedents for Korea’s modern beauty myth

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 2: Kwak Hyun-hwa (곽현화), Pin-up Grrrls, and The Banality of Sex and Nudity in the Media

- Bikinis, Breasts, and Backlash: Revealing the Korean Body Politic in 2012

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)

Hi James, thanks for this. Your analyses of the construction of Korean femininity are more disturbing for being so detailed – how do personality characteristics even get attached to face shapes in the first place? Anyhow, I appreciate the critiques and was wondering if you could have a go at this:

Dancing with measuring tape, the fat suit… it’s terrifying. Unless I’m totally misreading it and it’s empowering?

LikeLike

Thanks for reading, and for the suggestion. I would like to get my teeth into Hyomin’s new song and MV, but frankly, like a lot of things these days, there’s already a lot of good commentary out there by the time I can get around to seriously looking at something. Also, once you’ve been following K-pop long enough, then you begin to see the same themes time and time again, and wonder what you could really add to everything you’ve already said about them years before. Sure enough, one of those is messages of dieting and so on, which Stephen Epstein and I covered in our book chapter, with Hyomin’s role in Like the First Time featuring prominently in that:

Sorry for the long (and slightly cynical!) answer. It’s just that this blog is in its seventh year now, and I’m doing more and more related stuff offline, so I’ve been thinking a lot recently about its future — and realizing the reality of the above is part of that. Long story short, I’ve basically decided that I’ll continue providing translations of Korean news that non-Koreans would otherwise never see, plus working on things that no-one else is, and/or that (if I do say so myself!) I can claim some kind of expertise in (this post is a nice example of all three). Providing some critical commentary on the latest K-pop releases though, while they’re still playing on TV? Honestly, I just can’t compete with all the other excellent

, childlesswriters out there, many of whom — hell, most — know much more about music and K-pop than I ever will.Sorry for unburdening myself here. Thanks for listening! :)

LikeLike

That’s cool James, thanks for both the sources and updates on your activity. I agree, no point reinventing the wheel, plus it sounds like you’ve assimilated the source material and have widened a valuable niche applying feminist analyses for academic and international audiences. I look forward to reading more of your work about why these messages get disseminated and their roots in underlying socio-economic trends.

LikeLike

I think that the portrayal of women as infantalised in the fifties had much to do with the post-war need to get women back in the homes. That women had more than proven themselves as capable in the workforce, and able to function as as breadwinners in their own right, and left men feeling as certain underpinnings of society were now off center. Hence, films like “The Lady Says No”, which explicitly implies that women need to ‘let (former military) men be men”, and a greater emphasis on physical difference, which is one reason for the rise of beefcacake and bombshell figures in the fifties.

Not that infantalized “Blonde Bombshells” hadn’t existed since they appeared as a reaction to the end of the flapper era.

The description of the Lolita Egg look seems to fit Jean Harlow to a “T”. Simultaneous with Harlow’s rise was that of Shirley Temple, who often play gangster’s molls, and other “loose” types in 1932’s “Baby Burlesks”. These on-reelers had toddlers playing ‘adult’ roles. Her mother made the lingerie Temple wore in the one that I saw, which was nearly perfectly copied in “Bugsy Malone” decades later. Graham Greene was forced to hide out after in Mexico after calling her a “perfect totsy” in a review of “Wee Willie Winky” five years later.

Funny how a Brit could notice that America’s favorite child star was covertly sexualized to appeal to older men, while the American president could say “It is a splendid thing that for just fifteen cents an American can go to a movie and look at the smiling face of a baby and forget his troubles.”

On a side note, I’ve long wondered if a perceived (or desired) neoteny in Asian female appearance and/or behavior lies behind some of the incredible popularity of Japanese, HK and Korean media.

LikeLike