Tonight is a strikingly sensuous MV about a time of freedom and female friendship. But to what extent is it undermined or enhanced by its many erotic moments? To what extent are those just plain sexual objectification?

(Source: 미선씨의 위대한 하루 시즌2)

(Source: 미선씨의 위대한 하루 시즌2)

Time to answer the big questions that have been on your mind since Part 1 and Part 2:

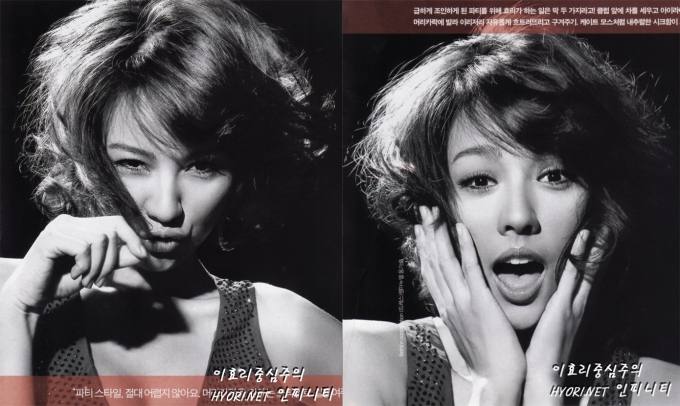

“Wait…is that Lee Hyo-ri? Or is THAT Lee Hyo-ri?”

Tonight may be a great song, but it’s a real headache keeping track of who’s who in the MV, and the one guide I found had two big mistakes. So, let’s clear up the five Spica members’ names first:

(From 1:07. All screenshot sources: Youtube.)

(From 1:07. All screenshot sources: Youtube.)

Partially, the difficulty is because many sites use Park Si-hyun’s old name of Park Ju-hyun (박주현; she legally changed it). Partially, it’s because Park Na-rae (L) and Park Bo-hyung (R) look so similar in it:

(1:12)

(1:12)

But mainly, it’s because there’s so many different costume, hairstyle, and hair color changes throughout, and much throwing of colored chalk dust. Also, it’s because there’s actually six people in the MV: Lee Hyo-ri features in many scenes in the first half especially, and looks a lot like Na-rae (or rather, Na-rae looked a lot like her then, but doesn’t in 2016):

(0:01)

(0:01)

(0:37)

(0:37)

Adding to that confusion, it doesn’t help that Na-rae was wearing that same white mesh cardigan just a little earlier (or that Yang Ji-won was wearing a very similar one at 0:47):

(0:23)

(0:23)

The giveaway is Hyo-ri’s tattoo though:

(0:38)

(0:38)

(2:28)

(2:28)

Compare this picture from Netizen Buzz last month:

As for what she’s doing in the MV, I’ll let Zander Stachniak of Critical Kpop explain (with the tweet and video inserted by me):

In 2013, B2M organized a mentorship between labelmates Lee Hyori and Spcia, the latter benefiting tremendously. The single, “Tonight,” was a return to vocally powerful music, and their first top ten song on the Gaon chart. Hyori and husband collaborated and produced the song, and Spica also seemed to take a page out of Hyori’s book with more of a “sexy” concept…

https://twitter.com/jetpack/status/746539156352937984…It seemed as though B2M saw the Lee Hyori connection as the way forward. Finally they were getting somewhere. In 2014, Spica realeased “You Don’t Love Me,” a ‘60s style jazz number unlike anything they had ever done before, but very much like Hyori’s most recent album. An extension, almost. The song was brilliant, quirky, a joy to listen to. But Spica’s identity was becoming harder and harder to locate. Which might explain why their best song since debuting only reached 16 on the Gaon charts. Somehow, Spica had slid backwards. (End.)

I’m a huge fan of Hyo-ri’s: hearing about her role is what motivated me to check out Tonight in the first place, and the MV’s sensuality is very characteristic of her. But appearing in it herself was surely too much. Let alone being the very first person the viewer sees:

And by coincidence, that was the first time I’ve seen the MV myself for several weeks. Seeing it with fresh eyes, now I realize I may have given the wrong impression in Part 1 and Part 2 sorry: it is not just an endless parade of female flesh. It is very much a sweet, sentimental memory of close female friends on some kind of trip, told in a non-linear, dream-like fashion. It feels almost churlish of me to critique it, when so many women have responded so positively to its charms.

Then I take another look at the following scenes, and don’t feel guilty at all.

The “Passive and Unthreatening Recipients of the Male Gaze” in Tonight

(0:17)

(0:17)

If all you knew of Tonight was girl-power hipster road-trip, then this might be the first scene that made you suspect there was a little more to it than that.

Not that I’m going to criticize it mind you. That teddy Yang Ji-won is wearing is supposed to be very form fitting. She does happen to have the largest bust of all the Spica members, but so what? If we start tut-tutting just because she’s in the scene, but wouldn’t if it featured a different member with smaller breasts, then that’s just body-shaming.

Instead, let me point out that you can’t unsee the ejaculation imagery in the suddenly rising balloon. (You’re welcome.) And, that although we get very brief glimpses of Kim Bo-a also wearing a teddy at the slumber party shown much later, it’s only Ji-won that we get to see like this there:

(1:40)

(1:40)

Thinking about why that was the case, and why the other three members were wearing such loose-fitting clothing at that party, I suddenly realized something obvious.

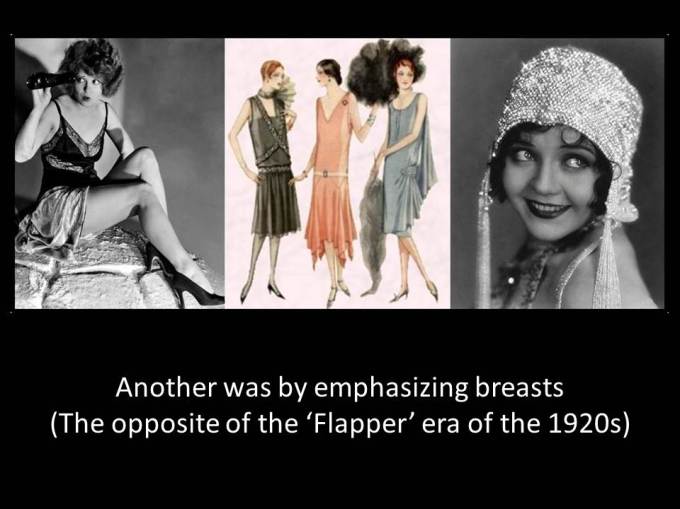

You know all those lying down scenes I made such a big deal of in Part 1 and 2? It turns out, it’s only Ji-won in most of them. And it’s her chest that we get to see the most of too.

I can’t believe I only just noticed. This is what staring at breasts for 10 weeks does to you…

(0:24)

(0:24)

(0:31)

(0:31)

(0:34)

(0:34)

(0:36)

(0:36)

(0:47)

(0:47)

(1:00; for a change, this time it’s Bo-a.)

(1:00; for a change, this time it’s Bo-a.)

(1:03)

(1:03)

Of this shot of Ji-won falling back into the pool, I’m thinking that on the one hand it’s a great metaphor for the viewer abandoning themself to their dream. But on the other that…boy, those are some great boobs. And you’ve got to appreciate the shots of her body too.

I’m not normally so crass. But however sensual, this element of the MV isn’t exactly subtle. Sometimes you’ve just got to call it.

As indeed with this next, very awkward scene with Si-hyun on her back, in which she’s wearing completely normal summer attire for a young Korean woman…if she were almost anywhere except in a swimming pool that is. And whose idea was it to bring a surfboard to a pool anyway, if not to give Si-hyun something to lie on for me to better admire her legs?

(1:17)

(1:17)

Yet for all its flaws, it was only through working out this scene that I realized the MV is supposed to be a dream. (Although I acknowledge that was already mentioned by other reviewers.) It was tough, because I took it very literally at first. Who the hell are the five of them supposed to be looking at, I wondered. How could that person be floating several meters above the pool? It only makes any sense if that person is the dreamer, who isn’t really there at all.

Should that context change our interpretation and/or criticism of any of the above scenes? I’d love to hear your thoughts. I do wonder and worry though, how accurately my screenshots are conveying that context, because of something I read recently:

My Women’s Studies class were watching Not a Love Story armed with Ruby Rich’s attack on the film. [It] is a documentary about pornography directed by Bonnie Klein which includes interviews with porn stars and feminist critics…Because Klein deployed traditional cinematic practices, Rich claims that the film cannot be feminist since it uses a camera ‘gaze’ which simulates, through intimate zooms, the typical vantage point of a male consumer of pornography. Rich deplores Klein’s use of a male cameraman and shots which turn the ‘viewer into a male customer normally occupying that vantage point’ (p. 408)…

My class largely rejected Rich’s reading, not because they disagreed with her technical deconstruction, but because, for them, the film’s meaning was lodged in the moving stories told by the women interviewed as much as in the camera movements. A purely visual reading, in other words, did not satisfy these women students. The voices of fascinating and independent women (however problematically presented) won out over the visual construction of spectator relations. The problem, then, for feminist criticism is that cinema identifications are not so easily and simply defined. Any attempt simply to deny that viewers are moved by what they hear, as well as by what they see, will create an imbalance.

(Feminism and Film, Maggie Humm, (1990, pp. 46-47.) My emphases)

Which I didn’t provide just to sound lurn-ed, but also because it’s a reminder that context is crucial for judging sexual objectification. Which there’s a lot more of to come in the MV.

On Positive Objectification

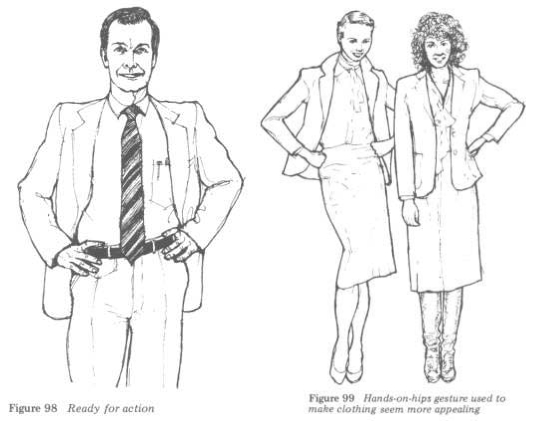

But I’ve already covered that issue in the post “Consent is Sexy: SISTAR, slut-shaming, and sexual objectification in the Korean idol system“, which is just as much of a #longread as this one. Let me confine myself here to highlighting just one source I used there then, for reasons I’ll explain in a moment:

According to Nussbaum, then: “In the matter of objectification context is everything. … in many if not all cases, the difference between an objectionable and a benign use of objectification will be made by the overall context of the human relationship” (Nussbaum 1995, 271) …Objectification is negative, when it takes place in a context where equality, respect and consent are absent…And it is benign/positive, when it is compatible with equality, respect and consent…

Nussbaum believes that ‘Lawrentian objectification’ (objectification occurring between the lovers in D. H. Lawrence’s novels) is a clear example of positive objectification. The passage from Lady Chatterley’s Lover that she quotes in her article describes a sex scene between two lovers. Connie and Mellor, in a context characterised by rough social equality and respect, identify each other with their body parts, they “… put aside their individuality and become identified with their bodily organs. They see one another in terms of those organs” (Nussbaum 1995, 275). Consequently, the two lovers deny each other’s autonomy and subjectivity, when engaging in the sex act.

However, Nussbaum explains, “when there is loss of autonomy in sex, the context is… one in which on the whole, autonomy is respected and promoted. … Again, when there is loss of subjectivity in the moment of lovemaking, this can be and frequently is accompanied by an intense concern for the subjectivity of the partner at other moments…” (Nussbaum 1995, 274–6) …Furthermore, Connie and Mellor do not treat each other merely as means for their purposes, according to Nussbaum. Even though they treat each other as tools for sexual pleasure, they generally regard each other as more than that. The two lovers, then, are equal and they treat one another as objects in a way that is consistent with respecting each other as human beings.

(Papadaki, Evangelia (Lina), “Feminist Perspectives on Objectification”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2015 Edition, available online)).

Of course, gratuitous, disembodied jiggly body parts are lecture one of sexual objectification 101; by all means, we can discuss Nussbaum’s perspective on that in the comments, or in that earlier post. But my main intention in quoting her is not quite so lofty.

Rather, it’s to explain why my initial reaction to the MV was so visceral. Nussbaum speaks to how, when I’m in the mood, I almost can’t help but stare at certain body parts of my wife’s. Yet far from feeling objectified, my wife mostly finds it amusing, and relishes the exclusive attention and focus given to those body parts later. Seeing Ji-won lying down in that tent in the MV, the camera gaze lingers on her body very much like I would on my wife’s, as I luxuriate in the feel of her skin and savor her scent. Say, on a rare lazy Sunday afternoon, before we both suddenly realize the kids will be in the playground for—OMG—a whole half hour.

I imagine something similar explains why some lesbian commentators’ appreciation of the MV is so strong too. It’s what makes it so evocative, and explains how what would otherwise strikingly sensuous MV—arousing the senses without the sexual connotation—is really much more of a sensual one, “gratifying the carnal, especially sexual, senses“.

And that’s great. I applaud the sensuality. I scoff at the notion that because men may be more visual creatures than women, that context and atmosphere and—heaven forbid—our actual relationships with the objects of our desire somehow aren’t important too.* Which is not to say I don’t also appreciate me some T&A of course, but then that’s all there seems to be to most “sexy concepts” in K-pop these days, which is why they tend to be quickly forgotten. Unlike, say, Bloom, which we’ll still be talking about 30 years from now.

(*Update: Further corroboration of that is demonstrated by users’ reactions to VR porn, which transforms them “from being a voyeur to a participant”, and tricks them “into experiencing something like intimacy.”)

But wait. With great difficulty, let me tear my eyes from away those screenshots with Ji-won for a moment, and start thinking properly again.

Because while Tonight does have romantic lyrics, the MV itself was about a girl-power hipster road-trip, right? If so, what are those scenes with Ji-won doing there? Why almost only her? And what about all these headless shots coming up too?

The Objectification in Tonight (and THAT Lesbian Scene)

Whose body parts belong to whom? I could find out, but that laborious process would be much less fun than it sounds. Besides which, the point is I shouldn’t need to.

(0:40)

(0:40)

(0:53)

(0:53)

(0:55)

(0:55)

(0:57)

(0:57)

Again, in an MV actually about relationships and/or sex, all those examples might be fine. Like I said, I often look at my wife that way, and at least I don’t feel evil when I do. But being so gratuitous here, they do appear to be classic examples to add to that sexual objectification 101 lecture, and strongly remind me of the recent “Headless Women of Hollywood” meme.

https://twitter.com/jetpack/status/747431571943133184And, speaking of things which seem out of place, it’s high time we examined that scene. You know the one:

(1:23)

(1:23)

(1:25)

(1:25)

(1:26)

(1:26)

(1:27)

(1:27)

(1:32)

(1:32)

(Source: Omona)

(Source: Omona)

If any scene can be said to be for a lesbian gaze, this is it. But it’s a terrible execution.

Among other things, Na-rae and Si-hyun are in completely different rooms. So when I first saw it, I didn’t think Na-rae’s undressing was even for Si-hyun at all, but that it was just for the heterosexual male viewer instead, with Si-hyun reacting to the audacity of Na-rae’s action. (My opinion is kind of moving back in that direction, TBH.)

Crucially, it just comes out of nowhere too. The only other one scene I can think of that hints at a romantic interest between two women—and I stress only hinting—is this one with Hyo-ri and (I think!) Na-rae:

(0:39)

(0:39)

And for sure, Hyo-ri pushes Na-rae down in it, who tumbles onto the bed in a most delightful fashion:

(0:46)

(0:46)

Or at least she would, were the MV not to segue into an awkward tumbling of Ji-won onto some grass instead:

(0:47)

(0:47)

And that’s it. Yes, really, with these next, final scenes most notable for that absence. Because again, they’re very sensual, and I’d venture that lesbian viewers can certainly appreciate them, for the same reasons as heterosexual men can. (See Part 1 for more discussion of reactions by lesbian viewers.) But we see no “intra-diegetic gaze” of a woman in the MV admiring another woman’s body in the same way, despite the many titillating opportunities provided.

(Bo-hyung at 1:08)

(Bo-hyung at 1:08)

(1:09)

(1:09)

(2:14)

(2:14)

(2:15)

(2:15)

(2:16)

(2:16)

(2:44)

(2:44)

Conclusion

When I showed Tonight to a perceptive friend of mine two years ago, he told me it strongly reminded him of I’ve Gotta Feeling (2009) by the Black Eyed Peas. That would indeed be a very interesting comparison to make: both are great songs, and both MVs are very sensual, but with many problematic depictions of the women therein. And both, ironically, seem to have been relatively overlooked by pop-culture writers, at least in that latter respect. That’s no big surprise for Tonight of course, which wasn’t very successful as explained, but it comes as a strange oversight for I’ve Gotta Feeling, which reached #1 on numerous charts worldwide.

The main difference though, is that the MV to I’ve Gotta Feeling matches its lyrics. Perhaps Tonight would have been more successful if it too had embraced its sensuality, rather than making that feel so blatantly pervy and tacked on?

Because, ultimately, it was?

What do you think?

Either way, I’d hate to end on such a despondent note, almost as if I didn’t even like the song and MV, let alone still love both. Let me part with you instead then, by choosing from one of its many charms that I alluded to earlier. This  scene, say, from 1:12, about which Laverne at Seoulbeats wrote (source, right: Yellow Slug Reviews):

scene, say, from 1:12, about which Laverne at Seoulbeats wrote (source, right: Yellow Slug Reviews):

The scene where Spica sway facing the wall (leaving us with a view of their backsides) is an example of a liberating and empowering direction; It’s not framed sexually at all. But the ice cream scene was and the MV would have been improved if it was eliminated.

For comparisons’ sake, a must read is I’m No Picasso’s thoughts about a similar Simone de Beauvoir nude.

And for even more fun, here’s the “male” version of the song:

And here’s the Areia trance remix. I still prefer the original, but I enjoy the slower tempo of this one too, which may be more apt for the MV:

Song Credits

Lyricists: Lee Hyori, Kim Bo-a; Composers: Nermin Harambasic, Anne Judith Wik (both worked on many songs on Lee Hyori’s Bad Girls album), Henri Jouni Kristian Lanz, William Robert Rappaport; Arrangers: 양시온, 김태현(also did Bang! by After School). (Source: Naver Music.)

Music Video Credits

Director: Yong Seok Choi; Assistant Directors: Edie Ko, Jungwoo Yoo, Oui Kim, Wonju Lee; Cinematographer: HyunWoo Nam (GDW); Art Director: Mina Jo; Cast: SPICA, Hyori Lee. (Source: LUMPENS; see here for a list of the many other MVs they’ve worked on.)

also looked slender, but compared to slightly square-faced beauties didn’t have many characteristics. It was massively popular, because it gave the feeling of a face you could see anywhere (

also looked slender, but compared to slightly square-faced beauties didn’t have many characteristics. It was massively popular, because it gave the feeling of a face you could see anywhere (

On the one hand, the Lolita Egg stimulates men’s possessiveness, whereas to women it turns them into wannabees. It’s a pretty face shape, but doesn’t give off a haughty, arrogant impression, proving very popular with men. Women who have it can pick and choose from among their many male followers (source right: unknown).

On the one hand, the Lolita Egg stimulates men’s possessiveness, whereas to women it turns them into wannabees. It’s a pretty face shape, but doesn’t give off a haughty, arrogant impression, proving very popular with men. Women who have it can pick and choose from among their many male followers (source right: unknown).

But in fairness to Lee Hyori, Doosan was in the midst of reorganizing itself into a holding company centered around heavy industries when it hired her, and in hindsight the same company that had just bought

But in fairness to Lee Hyori, Doosan was in the midst of reorganizing itself into a holding company centered around heavy industries when it hired her, and in hindsight the same company that had just bought

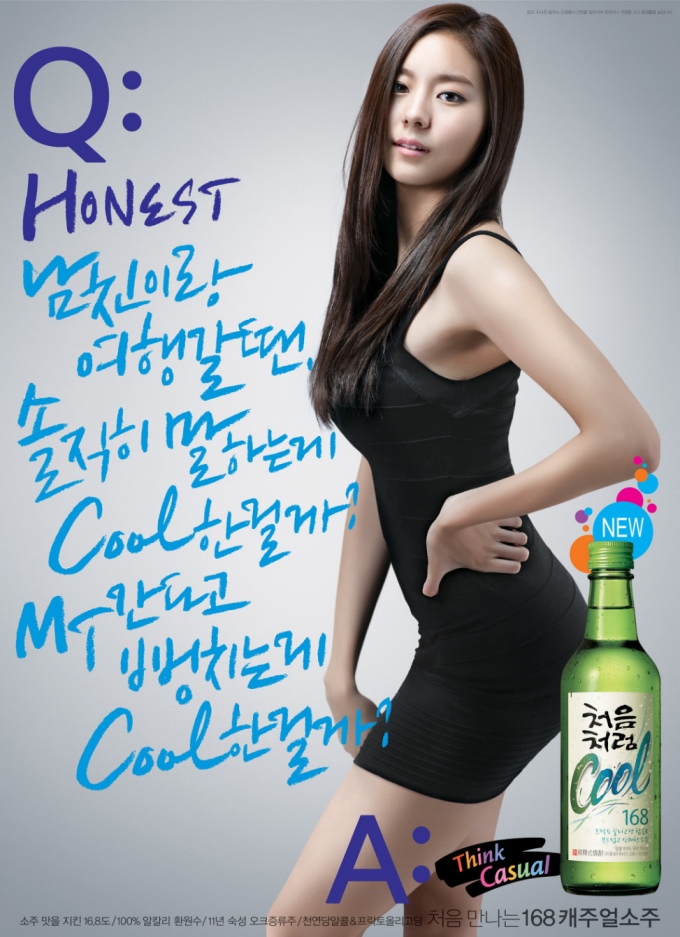

(Source:

(Source:

7)

7)