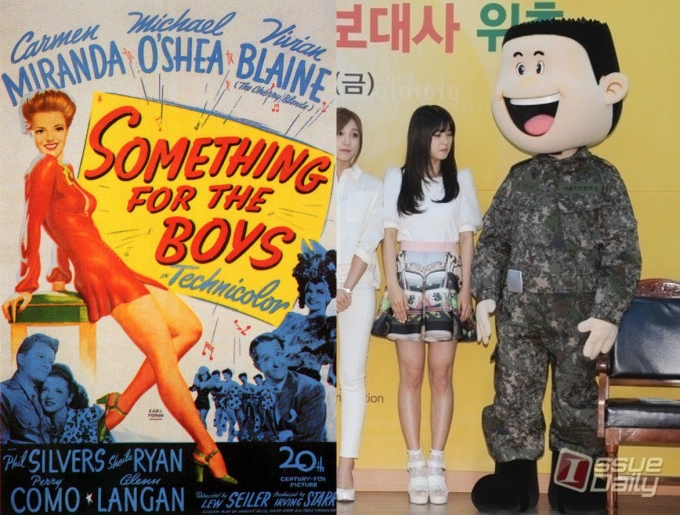

Sources: Left, Big Forehead Kisses; Right, 병무청 Twitter. The heading reads, “Thank you for choosing [to join] the military [early],” the subheading, “You are Korea’s real men.”

Sources: Left, Big Forehead Kisses; Right, 병무청 Twitter. The heading reads, “Thank you for choosing [to join] the military [early],” the subheading, “You are Korea’s real men.”

What could be more Korean than girl-group members in high heels and camo one-pieces, blossoming with aegyo for their big, strong oppas doing their military service?

What else but seeking out the cutest, most virginal group possible, then making them representatives for your entire military?

Last March, I learned that Apink had been selected as the first female PR “ambassadors” for the Military Manpower Administration (MMA), which administers Korea’s conscripts. Despite everything, it still felt jarring: what was a girl-group—any girl group—doing representing such a male-dominated (and notoriously sexist) institution?

The subway ad that sparked this post. Source: 23throom. Source, below: Pin Up: The Movie.

The subway ad that sparked this post. Source: 23throom. Source, below: Pin Up: The Movie.

Not realizing that appointments like theirs actually had a long precedent as I’ll explain, my first thought was to compare their recruitment posters to some of their (Allied) World War Two equivalents. I expected that most that featured women would present sexual access to them as a motivation for fighting (PDF download) and/or the denial of that access to the rapacious enemy. But to my surprise, most of the posters with women were actually for women, with the purpose of recruiting them for ancillary organizations and factory work. Borrowing “the seductiveness, sass, and self-assurance” of pin-up girls, Maria Elena Buszek explains in Pin-Up Grrrls: Feminism, Sexuality, Popular Culture (2006), they reminded women of their choices among active, formerly “masculine” paths in the public sphere, “in what must have felt like an abundance of  subversive opportunities.” And the contrast with Apink’s roles in the MMA’s campaign for men was striking.

subversive opportunities.” And the contrast with Apink’s roles in the MMA’s campaign for men was striking.

For Apink were not just some random girl-group. When they debuted in 2011, only one member was over 18, with another was as young as 14. So, whereas most entertainment companies relied on ever more provocative “sexy concepts” to get their groups noticed, Cube Entertainment chose to emphasize Apink’s cuteness and innocence instead. Those personas came across strongly in the campaign, indicating they likely played a big role in why Apink was chosen.

And that’s where it became problematic.

Not because I’m a grouch who thinks aegyo should only be enjoyed in moderation. But because the Apink members themselves, by then almost all grown women, increasingly complained about literally not being allowed to mature. Also, because it was disingenuous, those personas being very much at odds with the sexualized manner in which girl-groups are (naturally) viewed by conscripts, and are presented to them in practice. But most of all, because dig past the many, many layers of bullshit that can and probably will be used to disguise and/or justify this instance of Korea’s pervasive “lolita nationalism” (a.k.a., samcheon fandom for a cause), then what you’re left with is one damned patronizing, infantilizing vision of female gender roles and sexuality deliberately being promoted to the 250,000 young Korean men conscripted every year.

For years I’ve described Korea’s universal, mandatory male conscription as a profound socialization experience, which practically—and to an extent even legally—has or still excludes a great many groups from effective participation in Korean economic and political life, most notably LGBT individuals, the disabled, mixed-race children, and, of course, women. But sorry—it’s been a while since I’ve given an actual example of how that works in practice. Also, while it’s a still a must-read, it’s been ten years now since Seungsook Moon’s Militarized Modernity and Gendered Citizenship in South Korea came out, and, in hindsight, she barely mentioned the role of popular culture in supporting and propagating the ideologies outlined therein. So, to compensate for both, here’s Part 1 of a #verylongread below, and one which I hope Apink fans will realize has nothing against Apink themselves…

Supporting the Troops—A Quick History

Sources: left, @ThemeTimeBob; right, dcinside.

Sources: left, @ThemeTimeBob; right, dcinside.

There are many reasons no-one should be surprised by the appointment of a girl-group to represent the MMA. If anything, it’s stranger that it didn’t happen much sooner, because:

1) Korean girl-groups and female entertainers performing for the military in Korea is a significant part of Korean popular-culture, with roots going back to the Japanese colonial and US occupation periods, and with spillovers into performances for schools. So the notion that one such group would come to officially represent the military is hardly a radical step.

Also, there is the elephant in the room that is the historical role of prostitutes around US bases, originally with official approval. That’s a far cry from K-pop performances of course. But, if nothing else, it’s indicative of the Korean state’s long-standing, very collusive, and very objectifying view of women vis-à-vis the military.

Here’s Apink performing on a base themselves, shortly after they debuted in 2011:

(Watching the conscripts, no-one can blame them for their over-the-top reactions to, well, female humans. But it all comes across as a little creepy when you realize they’re professing their love for middle-school girls, and begs the question of what such a young group was doing there.)

2) Just a cursory examination reveals a host of regular, albeit usually temporary “honorary ambassadorships” by girl-groups and female performers for a range of organizations. Examples include the Ministry of National Defense appointing 4Minute as ambassadors for its Korea Armed Forces’ 29 Seconds Film Festival; the appointment of Hello Venus to make the music video/dance/song Soldier for the recent 6th CISM Military World Games;

…the Seoul Metropolitan Police Agency, which also relies on conscripts to a large extent, appointing BESTIE to make a stirring song about stamping out school violence;

…and the appointment and later promotion of IU as an honorary police officer by the national police agency. Indeed, that was over a year before the appointment of Apink by the MMA, which makes me wonder how far back using women to advertise and promote still overwhelmingly male organizations goes?

I’m thinking probably quite far, given what I’ve just been learning about regular girl-group performances for the police. Which gives me a chance to totally stan this amazing 2NE1 video by way of example:

3) Korea, along with Japan, has one of the highest rates of celebrity endorsements in the world (among developed markets). This includes being the face of public campaigns and/or for governmental organizations, which sometimes have a profound impact on public opinion.

One memorable example is the National Election Commission’s choice of The Wondergirls to encourage voting in local elections in April 2008, which was somehow best achieved by outfitting them in faux, tight-fitting school uniforms, and despite—notice a trend here?—two members still being of middle-school age (15):

Two years later, Girl’s Generation would do something similar (although by that stage, no members of that group were underage). As described by Yeran Kim in “Idol republic: the global emergence of girl industries and the commercialization of girl bodies” (Journal of Gender Studies, 20:4, 2011):

At Korea’s 2010 national election, the most famous girl idol group, Girls’ Generation was recruited for the campaign to promote citizens’ participation in the vote. Girls’ Generation released a single, album and music video of the campaign song titled ‘LaLaLa’. Girls’ Generation also appeared on TV campaigns in which each girl member was visualized as a Tinkerbell-like mini-sized icon, while the citizen voters were represented by male citizens. Girl idols are equally utilized for important international events; for instance, Girls’ Generation were appointed as Customs Promotion Ambassadors in preparation for the G20 Summit Conference in 2010 in Seoul. The girl idols are, at least in appearance, presented as agents who have the power of motivating, seducing or interpellating citizens to become involved in the project of global nation building.

Also, to get yet another elephant in the room out of the way early on. (With K-pop, they tend to come in herds.) Yes, a lot of the things described in this post were modeled on Japan:

“Here’s a cheerleader telling you everything you need to know about Japan’s population trend: Old people up, young people down.” Source: Fusion.

“Here’s a cheerleader telling you everything you need to know about Japan’s population trend: Old people up, young people down.” Source: Fusion.

4) Though (probably) few in number, there have been some prominent gender-bending Korean ads in recent years. Examples include: Kim Sa-rang endorsing Gillette razors; Hyun Bin endorsing a tea-drink that supposedly gives you a V-line (albeit part of a process to encourage men to get hitherto “feminine” V-lines, thereby increasing the market); various male celebrities endorsing lingerie; and Yoo Yeon-seok endorsing feminine-hygiene products:

Sources: Nemopan, 초아의 퍼스트드림 이야기

Sources: Nemopan, 초아의 퍼스트드림 이야기

5) The Korean military currently has one hell of a PR problem. In short, because it is still very much stuck in the 1970s. Let me explain.

Seventy-five percent of Korean soldiers are conscripts, who are paid minimal wages, and have to endure “abysmal living conditions.” Essentially, they’re a huge, convenient slave labor force, who not only “have to pave roads in the mountains or dig up snow” for the government, but have to do even the most menial of tasks too—”such as cleaning the pool of the general’s house.” This discourages expensive mechanization and modernization, as well illustrated by the following anecdote given by Ask a Korean!:

…the Korean has a friend who spent his military years in the eastern mountain range in Korea. One day, the general decided that he would have fresh sashimi for his guest. The Korean’s friend and his squad mate drove in a truck for two hours to the shore, and managed to acquire fresh, live fish. But how to bring them home fresh and alive?

A normal person’s answer would be, “Rent a truck with equipped with a tank and an air compressor, the kind that would deliver live fish to sushi restaurants.” But remember, this is the Korean military. It does not have the money to rent such a truck, but it does have the manpower of two soldiers.

So what did the Korean’s friend do? He sat in the back of the truck, churning the water in the tub so that air would go in and the fish would be kept alive. (His squad mate got to drive the truck because he joined the military a few months ahead of the Korean’s friend, therefore outranking him.) This was in the middle of winter, and the truck bed was exposed to the freezing wind as the truck drove into the mountains. The Korean’s friend nearly froze to death, but the fish were alive until they were served on a plate that evening.

Stories of this type, coming out of Korean military, are dime a dozen.

But for the victims, such stories are probably only amusing until well after their service is completed. Because with such perverse demands on conscripts, comes an unusually strictly defined hierarchy and secretive nature to ensure compliance. This leaves them vulnerable to sexual and physical abuse, which has culminated in a spate of high-profile suicides and killings in recent years. (Including on the very day I typed this.)

What’s more, this unprecedented media scrutiny comes at a moment when it’s increasingly struggling to maintain its numbers, as Korea’s low birth rate begins to make its impact felt. Probably then, the military is now very concerned about softening its image.

(That said, currently it has more men wanting to sign up than there are spaces available, but that’s only because they want to get their conscription out of the way while the job market is so terrible. Indeed, so terrible in fact, that even women are showing interest in the limited—but growing—number of positions open to them, despite the extreme discrimination and harassment they face once inside.)

When the Korean police had the same problem, this was one of their solutions:

The male is called “Podori,” the female “Ponsuni.” Yes, that’s really Podori in his riot gear on the right. Source, left: Chuing. Right: unknown.

The male is called “Podori,” the female “Ponsuni.” Yes, that’s really Podori in his riot gear on the right. Source, left: Chuing. Right: unknown.

Did I say I was surprised to see a girl-group in camo? I didn’t say that, someone else must have. Because anyone up to speed on K-pop and the Korean media could have seen the time was ripe for a girl-group to represent the MMA. The cutesier, the better.

But Why Apink?

Source: APinkPanda.

Source: APinkPanda.

To many of you reading, who are already aware of Apink’s reputation, probably I’ve already answered that question. However, you could argue that Apink was chosen simply because of their popularity at the time. You’d be wrong, but I admit it’s a plausible first explanation. For instance:

- In April, they had the 2nd largest female(!?) fandom, after Girls’ Generation

- Also in April, their “Mr Chu” grabbed the Number 1 spot on the K-pop Hot 100

- On the strength of that, some considered them a “national” group akin to Girls’ Generation (although others felt that designation was premature)

- They planned to make their debut in Japan that Autumn (which proved to be very successful).

- As “the hottest girl group of 2014,” in August they were cast for the third season of Showtime

Source: TickTalk.

Source: TickTalk.

Technically though, all of those were after their appointment in March (although they’re still indicative). Possibly more influential then, was their winning the military charts in January, which apparently are a thing. Here’s a video about that and some screenshots of their reactions to the news, which give strong hints of the sorts of roles they’d be performing for the MMA campaign two months later:

Jung Eun-ji: We are like [the soldiers’] little sisters next door…

Jung Eun-ji: We are like [the soldiers’] little sisters next door…

…the soldiers must have felt we were familiar…

…the soldiers must have felt we were familiar…

Park Cho-rong: (To the soldiers) Girl-groups are like the star candies in the hardtack snack…

Park Cho-rong: (To the soldiers) Girl-groups are like the star candies in the hardtack snack…

…We will try to sing a lot to help keep your spirits up…

…We will try to sing a lot to help keep your spirits up…

Further adding to the notion that Apink was chosen simply for their popularity, in the year and a half since their appointment the MMA has been happy to have a range of girl-groups pass on cutesie messages or songs to cheer the troops up. Regardless of where their reputations fell on the virginal-cutesie-aegyo to slutty-sexy-concepts scale:

Further adding to the notion that Apink was chosen simply for their popularity, in the year and a half since their appointment the MMA has been happy to have a range of girl-groups pass on cutesie messages or songs to cheer the troops up. Regardless of where their reputations fell on the virginal-cutesie-aegyo to slutty-sexy-concepts scale:

For example, from 9Muses this September:

From two members of SISTAR (I can’t identify the male rapper sorry):

From EXID in July:

From Hyeri of Girl’s Day:

From GFriend:

Indeed, check out the video history of the MMA Youtube channel, and barely a month goes by without some girl-group making an appearance. Here’s 4Minute in September 2014:

And here’s Ladies’ Code in a video uploaded in December 2014. Somewhat strangely and tactlessly, that was actually two months after two members (2nd and 4th from the left) had died in a traffic accident:

Add that Apink’s popularity rapidly moved on to other groups, the implication of these examples is that any girl-group would have done really, and may well have been chosen if they’d been more popular at the time. And sure, why not? After all, despite the constant bullshit about girl-power from the Korean media, the Korean government, and Korean entertainment companies, most supposedly “sexy” and “mature” girl-groups seem to combine their revealing costumes and erotic dances with off-stage personas that are just as saccharine as their “cute,” “innocent” counterparts.

As one might expect with, usually, everyone but the women themselves telling us how grown-up and independent they are.

But with sexy groups, there is always the danger that their provocative costumes and choreography will overstep the limits of favorable netizen and public opinion. Also, and in particular, at about the same time Apink were appointed, many K-pop groups were beginning to suffer from dating “scandals”—that is, being revealed to be in relationships at all—with the women receiving the brunt of fans’ anger (from female fans for dating “their” male idol, from male fans for not “waiting” for them instead). Without condoning the double-standards behind that backlash, and indeed deploring those fans whose liking of a celebrity is contingent on his or her sexual history, I can appreciate why relationships are a sensitive subject for conscripts, many of whom either split up with their girlfriend before enlisting, or constantly fear that she’s cheating on him while he’s serving. (See the 2008 movie Crazy Waiting for an exploration of this.)

(That being said, the girlfriends have equal cause for concern, as it’s not uncommon for conscripts to visit sex workers.)

So if a cute, innocent, non-dating girl-group was required, why not select the group with the strongest reputation as such, and the least likely to radically change?

Indeed, one so strong as to be blatantly contrived for ajosshi/samhcheon fans? For instance:

- While promoting their third mini-album in July 2013, Apink told an interviewer that Cube Entertainment suggested that they transition to more mature concepts, but they wanted to maintain an innocent one. They also pointed that several members were underage, preventing the group from doing those sexy concepts. (Although only one—Oh Ha-young—still was as of March 2014, and she turned 18 that July.)

- In April 2014, it was revealed that 20

year-old So Na-eun had never dated. Yes, technically after they’d been hired by the MMA, but again it’s indicative (I’m sure I could dig up earlier examples).

year-old So Na-eun had never dated. Yes, technically after they’d been hired by the MMA, but again it’s indicative (I’m sure I could dig up earlier examples). - Also in April 2014, and in particular, they claimed that as no members had ever even kissed, then “they [had to think] of their fans while dancing the key choreography moves for Mr. Chu.“

- That was because they described it as “a pop dance song about a first kiss shared with a loved one, featuring Apink’s bolder but still shy way of confessing love.” But not so bold though, as to further stress the sensibilities of delicate fans, who had been concerned about a possible concept change ever since they saw the members wearing—wait for it—red lipstick on the album cover.

That is to say, the Korean media made that last claim, which is never shy of putting the concerns of ajosshi/samcheon fans front and center; click on the GIF above to see what (generally quite knowledgeable) Omona! They Didn’t! commenters thought of all that, and for more examples of the Lolitaesque subtext to Apink’s repeated claims of innocence. I’ll return to those in later posts, as I will the third elephant of the herd: that, all that time, the Apink members may have just been parroting the lines provided to them by Cube Entertainment, as indeed they may have been later when they started expressing their frustrations with their continued infantilization—an issue at the heart of how we judge K-pop, yet something that we usually just don’t know.

But we do know that, whether speaking for themselves and/or their employers, the change in tone is significant, and, having just made a deal with the MMA, not exactly in the latter’s interests. We also know that, even just judging by the campaign alone, that a cute, innocent group was indeed required for it, and obviously so:

Source: MMA Facebook Page; left, right

Source: MMA Facebook Page; left, right

These poster templates were used often, with the text changed as per necessary. The titles in these ones say:

Left: Those soldiers who make the bold choice to make the army your career (and get paid), we cheer for you.

Subheading: You can also choose to be in the special forces.

Right: Thank you for choosing [to join] the military [early].

Subheading: You are Korea’s real men

Source: CSBNTV

Source: CSBNTV

The MMA’s tweet reads (the poster is about the same thing):

If you write a letter, you will receive a mobile voucher [you can spend at coffee shops etc.] #MMA So let’s write a letter to the soldiers! #Apink #Nam-ju wrote a letter too!

And Kim Nam-ju’s own “letter” reads (see here, here, here, here, and here for similarly-themed messages in the series from other members):

Hello, this is Nam-ju from Apink! You are having a hard time, right? Aww…But I want you to always cheer up and find strength. Hee-hee. While listening to our songs, always cheer up and eat well and plentifully…I hope you get stronger. Ha ha ha…since friends the same age as me (in our 20s) are also doing their military service I worry more and more (cry cry). Always cheer up! If you laugh, you’ll be happy! Smile! I love you Korean soldiers! (Salute!)

Source: Mogahablog

Source: Mogahablog

Rest assured, there’s much more where that came from.

But why didn’t I just lead with all these examples? Why have I so labored the point that Apink was so well suited to the cutesie MMA campaign, when probably nobody, not even the most dedicated of Apink fans, needed convincing in the first place?

Good questions.

The main reason is that to critique the MMA campaign, and specifically to demonstrate that it was disingenuous, you need to show the disconnect between the intent and the reality. But I can’t definitively claim that Apink wasn’t just chosen for their popularity in early-2014 of course. Or, for that matter, that they weren’t just chosen because of some special financial arrangements between the MMA and Cube Entertainment, that simply weren’t offered to and/or possible with other entertainment companies for their own groups. Again, we just don’t know.

What we can say though, is that entertainment companies and the military are joined at the hip. That away from the performances on bases that get most of the media’s attention, girl-groups of all stripes are constantly presenting the same sorts of cutesie messages to conscripts, and acting like children in front of them. That, even if Apink wasn’t necessarily the only group able to fulfill that role on a permanent basis, that it was the most reliable choice to do so. And, lest we forget, that the companies or institutions doing the hiring of K-pop groups that call the shots, and that entertainment companies are only too willing to compromise their groups’ brand images or concepts for the sake of the hard income their advertising campaigns provide. A lesson I personally learned from DSP Media, who quite literally presented a new, very womanly side to KARA through the choreography to Mister back in the winter of 2009, only then to have them acting like my children in a commercial for Pepero by the following spring:

Source: FLV

Source: FLV

Ergo, the MMA wanted a cutesie, virginal girl-group, and that’s what they got. But how about the conscripts themselves?

I’m sure you can guess. But it’s always best to get first-person accounts, so I’ll provide two in a later post (update: in Part 3). Then, because not all of you may share my instinctive distrust of all things aegyo, in another I’ll consider an interesting perspective on Apink’s from May 2012, which—dare I say it?—demonstrates it can have some positives when done willingly by and for teenage girls…but which makes the negatives of young women performing it unwillingly for men in 2015 all the clearer. Finally, I’ll discuss the alternative gender roles the MMA could have presented in their campaign, as suggested by those World War Two recruitment posters.

I really don’t like making the split, as frankly this post has been a real labor of love for the past *cough* three months, which I feel works best at a whole. But at a combined total of over 10,000 words, it’s a necessary, reluctant concession to reality. Please help me make the best of it then, by adding your own thoughts in the comments, which I’ll consider and maybe incorporate as I finalize the remaining post(s). Thanks!

(Update) This post and the intended follow-ups ultimately became an ongoing series:

- Part 7: The Korean Conscription System Promotes a Servile, Subordinate, Sexually-Objectifying View of Women. Here’s How.

- Part 6: How does military conscription affect Korean gender relations and attitudes to women?

- Part 5: South Korea’s Invisible Military Girlfriends

- Part 4: 17-Year-Old Tzuyu: “A Special Gift for Korean Men”

- Part 3: Korean Lolita Nationalism: It’s a thing, and this is how it works

- Part 2: Male Privilege at Korean Universities

- Korean Sociological Image #92: Patriotic Marketing Through Sexual Objectification, Part 1 (Before it acquired a life of its own, this post was supposed to be the follow-up to this)

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 6: What is the REAL reason for the backlash?

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)

Thank you for writing this. Has always been on my mind.

LikeLike