If queer women say they love the MV to Anda’s Touch, this cishet man is going to listen. Not to self-appointed gatekeepers who insist women are only about the feels.

Estimated reading time: 20 minutes. Source, all screenshots: YouTube

Estimated reading time: 20 minutes. Source, all screenshots: YouTube

Face-sitting. A woman’s point-of-view shot as Anda kneels in front of her crotch. Women making out in the background. Anda admiring another woman’s vagina, beaming at the viewer in anticipation. The complete absence of any men. Anda lying in bed as another woman appears on top of her. Spinning the bottle. Anda loving all of it, as the MV to Touch relentlessly serves-up its women to its sensual, strikingly objectifying queer female gaze.*

Among self-identified queer female fans of K-pop and allies on social media, I’ve yet to find a critic. And who can blame them? “Queers are generally invisible in South Korean media,” researcher Chuk Tik-sze explained in her 2016 study on their representation, “and lesbians are more completely missing.” As if to prove her point, many viewers didn’t even notice the sex in Touch when it came out in June 2015, so low were their expectations of ever encountering queer content in K-pop.

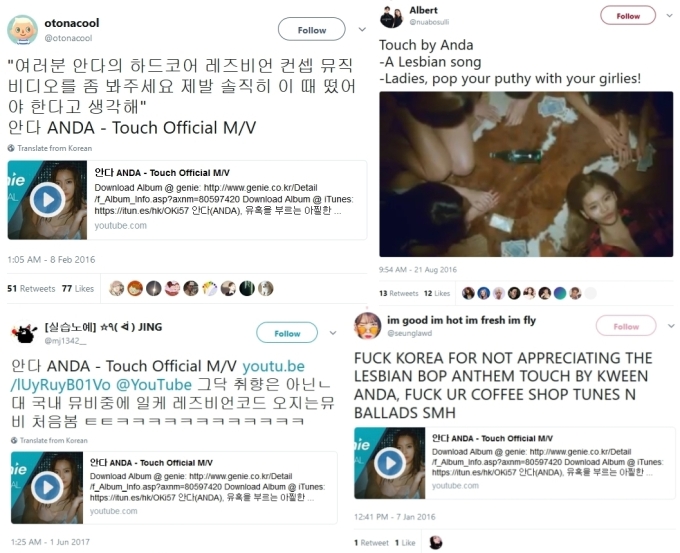

When people did get what the MV was about though, they really, really got it:

Yet as any lesbian perusing heterosexual porn can attest, simply replacing the sex of an objectifier does not necessarily a queer female anthem make. To many seekers of queer content, authenticity is more important, and in this respect the MV seems lacking. The lyrics are gender-neutral. Live performances lacked any sapphic elements. Before it came out, none of Anda’s other songs or MVs had any queer themes, nor have any since. If she is queer, then she’s yet to come out publicly, nor given any other indication of that beyond this MV.

In short, it may have been nothing more than a gimmick, aimed at drawing attention to a catchy but otherwise lackluster song.

I can appreciate that desire for authenticity. In spite of that, Touch is still for queer women’s gazes.

Why? Because queer women said so.

Touch would be no hit. But the reaction from queer women, of which the above represents just the tip of the iceberg, was overwhelmingly positive. Whereas any haters were remarkably silent for the internet.

That doesn’t mean queer women seeing it for the first time have to like it. It’s sweaty, it’s crude, it’s bush league compared to guaranteed queer female film classics like Carol and A Portrait of a Lady on Fire. But as a cishet man, I don’t need to think twice about prioritizing the feelings and reactions of the queer women who have actually opined on it. So, no matter however shallow it may be, it is still on the same spectrum as those. It’s there.

I wasn’t content with simply relying on fan reactions to determine if any future queer-looking media text spoke to the queer female gaze or not though. I wanted some sort of framework anyone could apply, or a list of questions to ask. So, I googled.

I wasn’t completely naive when I did that. I did expect there to be much less out there than for the heterosexual male gaze (henceforth, “male gaze”).

I definitely didn’t expect that discussions about the heterosexual female gaze (henceforth, “female gaze”) had only really taken off in the last few years though, not that on the queer female gaze (or lesbian gaze) still barely at all. That over forty years after Laura Mulvey got the ball rolling with the men, that writer and director Jill Soloway could plausibly claim that “[M]edia that operates from the nexus of a woman’s desire is still so rare. We’re essentially inventing the female gaze right now” (my emphasis). And especially not that, during that process of invention, Soloway and just about every other commentator on the female gazes would be so concerned about stressing that women are all about the feels, that they would forget that women do also like looking too, whether at men or at women. Let alone that men who look at women can also have feelings too.

If only I was exaggerating. Ultimately, I had to come up with those questions myself. (Skip to the end if you’d like to read them now.)

*Update: It’s been pointed out to me that my notion of the term ‘queer female gaze’ perhaps has some issues. To clarify then, my specific meaning by it is “the gaze of all people who identify as women, who are (not necessarily exclusively) sexually attracted to people who also identify as women.” I hope that clears up those issues, but am happy to be educated as to if any remain, or if my clarification has inadvertently raised new ones.

This Series

Photo (edited) by Ike louie Natividad from Pexels.

Photo (edited) by Ike louie Natividad from Pexels.

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and I’ll provide truckloads throughout this series. But what am I claiming exactly? So that there’s no confusion, let me devote this opening post to outlining the gist of my arguments, and provide some definitions.

In so doing, I repeatedly accuse commentators on the female gazes for making sweeping generalizations…only to lay myself wide open to the charge that I’m doing exactly the same about them. So, I will provide some examples here as I go along, which may mean some some repetition in later posts. But that’s no biggie: I encourage readers to take absolutely nothing of what I say at face value, and I am happy to provide dozens of links in the comments now for anyone who doesn’t want to wait for them until later posts.

Photo (edited) by Marcio Nascimento from Pexels

What we Bring to the Male Gaze

First, it can be a surprise to learn that commentators on the female gazes often devote a lot of time to the male gaze first. But it makes sense: the male gaze is much better known, and it helps in forming a contrast. Unfortunately, that also means there’s already a natural tendency to stress differences rather than similarities.

Next, it turns out there’s actually two male gazes evident in many of those discussions.

First, there’s the literal male gaze, which refers to how cishet men look sexually at women, and the perspective which is prioritized to the exclusion of almost all others in the media. In my experience, this is what the overwhelming majority of people think of as the male gaze, unless they’re educators or writers, and is the definition of male gaze I’ll overwhelmingly be using too.

(Yet another use of the term is to refer only to that domination of cishet male perspectives in all forms of media. Like when Lady on Fire director Céline Sciamma said that “Ninety per cent of what we look at is the male gaze,” for example, or when cinematographer Natasha Braier argued it’s so inseparable from cinema, that a female gaze is simply not possible.)

Next, there’s the abstract, academic male gaze (henceforth, “Male Gaze”). To explain what it means, consider the source: Mulvey’s book chapter “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in 1975, which I’m sure you’re all of aware of and many of you may even have read too.

But, if you are one of those who’ve read it, then I’ll wager…only once or twice perhaps? As a freshman, many years ago?

Because even if I’m really only just projecting, please do check out it again now, and admit it—it’s dense. Despite what it’s best known for, it’s mostly devoted to extremely esoteric, psychological topics like ‘phallocentricism’ and ‘fetishistic scopophilia.’ Colleagues of mine, who’ve assigned it as tutorial readings at the beginnings of their careers, have learned the hard way from their student evaluations to avoid it later.

Frankly, most of it is entirely above my head, as is much of the voluminous scholarship it’s given rise to.

That is not necessarily a criticism, or even a problem—we all use many concepts to understand the world without understanding all their nuts and bolts. As Lindsay Ellis diplomatically puts it below (2:44), the chapter really shouldn’t be considered “so much as a holy text as a jumping-off point.”

However, it does mean there’s a very abstract, academic Male Gaze of all that scholarship out there. And in my experience, one that’s frequently used interchangeably with the literal male gaze by non-academic writers. This leads to a lot of confusion, and, given the authority with which the Male Gaze comes, can easily come to dominate our understanding of the former.

Or, in other words, something about the abstract concept that may sound—and indeed be—perfectly reasonable in a Film or Gender Studies journal, but absurd if it was spoken of in a non-academic context about living, breathing, flesh and blood cishet men, nonetheless easily can and often does get done so anyway.

Take queer feminist critic Rowan Ellis‘s very first line on the subject in Bitch Flicks for instance, that it means “(t)he sexual objectification of passive female characters.” She doesn’t follow my m/M convention, so which gaze was she referring to? If her comment is about the Male Gaze, then that sounds very plausible—it sounds very much like something a Gender Studies scholar would say, and which I’m not knowledgeable enough to critique. But was that the type of gaze Ellis was referring to? Only by specifically asking ourselves that question and looking can we determine, indirectly through her saying the concept under discussion “can  be seen literally as a gaze,” can we resolve that she was indeed referring to the Male Gaze—and realize just how easy it would be to take away from her original comment that men’s literal sexual gaze is inherently objectifying.

be seen literally as a gaze,” can we resolve that she was indeed referring to the Male Gaze—and realize just how easy it would be to take away from her original comment that men’s literal sexual gaze is inherently objectifying.

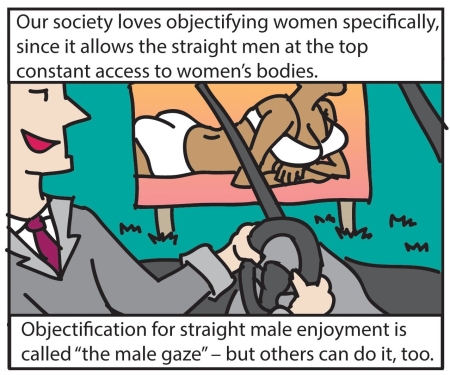

Or take the panel above from M.Slade‘s cartoon in Everyday Feminism entitled “Am I a Queer Woman Looking Through the Male Gaze?”. Again, I think it’s the Male Gaze, but it’s much more unclear this time.

Either way, it’s true that perhaps most readers wouldn’t need reminding of Suzannah Weiss‘s rare caveat, also in Everyday Feminism, that the Male Gaze “is not necessarily the perspective of most men, but rather, society’s notion of a ‘normal’ man’s perspective” (my emphases), and it’s patronizing of me to imply they would. I hope so. Given my professed ignorance, I’m not going to claim that Ellis or Slade are necessarily wrong about the Male Gaze either, or that a hell of a lot of men do indeed negatively objectify women. And yet somehow, a hell of a lot of commentators on the female gazes genuinely do seem to believe that cishet male desire is nothing but that overwhelming urge to objectify. The Male Gaze is the male gaze as it were. And again, because as I’ll demonstrate, I’m only confident in making that accusation because they literally say so. And/or, indirectly by outright denying that women can objectify too.

Perhaps they arrive at that position because, as Alina Cohen explains in The Nation, much like ‘white privilege’ and ‘heteronormative,’ the term ‘male gaze’ is “utilized mostly by those who seek to destroy the phenomenon it identifies.” I’d put it even stronger: absolutely no-one reading this has ever used it in a positive or even neutral sense until now, myself included. Indeed, it comes across as so utterly tainted in my readings, that I completely understand why commentators would feel compelled to distance female desire from it—and to ignore, dismiss, or vilify those women who exhibit the “male” traits they associate with it, as I’ll give an example of a little later below.

Photo by Charles Roth from Pexels

Absolutely Everything a Woman Creates is the Female Gaze

À la The Onion’s classic article about “empowerment,” further adding to all the confusion is that the female gaze has recently become somewhat of a catch-all buzzword. As Cohen puts it, the term “simply functions according to its users’ needs,” to the extent “when women direct films, take photographs, make sculpture, and even write books or articles, they’re often said to be harnessing [it].”

Just about every link in this post leads to many examples of the many fruits of all the discussions now being had about what difference the sex of the person behind the lens makes. Important and overdue questions are being raised about what it means to be a male artist of the female nude in the #MeToo era too. But all these conversations are diminished by numerous touted definitive female gaze photo collections sharing no more commonality than having been taken by women, and with few obvious differences with how men would have approached their subjects either.

Even photo collections by men have been exhibited as examples of the female gaze too. Which actually isn’t as absurd as it sounds—another topic to be raised in this series is to what extent men, with sufficient input from women, can create content for the female gaze, as well as cishet people for queer content—but it does go to show how the term can mean just about anything.

On top of that, in the last two years especially, it seems that every other commentator on the female gazes—and almost every reviewer of Lady on Fire(!)—uses the terms not just in a literal sense, but also to describe the movement to challenge the aforementioned erasure of women in general, WOC, queer women, and so on in popular culture, and especially their under-representation in its production. (The “Female Gaze,” I’ll call it.) I’m 100 percent on board with that, but it doesn’t help when that meaning is used interchangeably with its literal one.

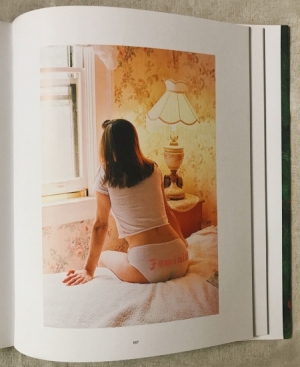

(In an excerpt from her book Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze, editor Charlotte Jansen seems to be saying she was originally angry about the picture ‘Yani, New Jersey, 2015’ by Mayan Toledano, but changed her mind because the photographer was a woman. If so, is that identity politics gone mad, or does she have a point? Image source: Maiden Noir)

(In an excerpt from her book Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze, editor Charlotte Jansen seems to be saying she was originally angry about the picture ‘Yani, New Jersey, 2015’ by Mayan Toledano, but changed her mind because the photographer was a woman. If so, is that identity politics gone mad, or does she have a point? Image source: Maiden Noir)

To better understand why commentators on the female gazes (and hence male gaze) make the calls they do, I’ve really tried hard to place myself in their shoes. I’ve noticed over 99 out of 100 of them identify as women (prove me wrong). That they’re justifiably outraged about the under-representation of women, their stories, and their ways of seeing the world in popular culture. That they’re sick and tired of the camera encouraging both men and women to look at the latter through an objectifying, domineering, leering lens.

But now, they have a chance to do something about that by writing or talking about the female gazes, or even by making their own media texts themselves.

Sources left and below: unknown. Source right: @maryneelahaye.

They have very limited time or space to do so though. People will surely understand if they make some necessary generalizations about men in the process, who are not even their focus.

Unfortunately, sometimes those generalizations really do go too far. Time and time again, confident, matter-of-fact declarations about all cishet men and male desire get provided that are often no more than caricatures.

To complain about that may seem like I’m just making a typical, unhelpful “not all men” retort. But I’m really not. Its not deflecting the conversation, because the women themselves are already talking about men. Also, it’s not missing the point, because like them, I only talk about men with the aim of better understanding the female gazes. For if those are defined largely in opposition to stereotypes of men, then those of women are surely going to be just as crude and useless, utterly failing to account for the likes of awkward, lascivious Touch fans.

To complain about that may seem like I’m just making a typical, unhelpful “not all men” retort. But I’m really not. Its not deflecting the conversation, because the women themselves are already talking about men. Also, it’s not missing the point, because like them, I only talk about men with the aim of better understanding the female gazes. For if those are defined largely in opposition to stereotypes of men, then those of women are surely going to be just as crude and useless, utterly failing to account for the likes of awkward, lascivious Touch fans.

It’s time to start pointing fingers.

The Burden of Proof

Re-enter Soloway, whose keynote address on the female gaze at the 2016 Toronto International Film Festival occupied the top spot in google searches until articles about Lady on Fire recently displaced it. Soloway, who “now identifies as a gender non-conforming queer person,” and is the award-winning creator of the immensely popular Transparent TV series, which has been “a major force in bringing discussions of trans rights to the mainstream,” was clearly a well-liked, very motivating speaker at the festival. This, despite shitting on so many women so quickly into her address (5:15-6:55):

The opposite of the male gaze, if taken literally, would mean visual arts and literature depicting the world and men from a feminine point of view, presenting men as objects of female pleasure.

So, okay, I guess in it’s most simple that would be like, Magic Mike if it were written, directed and produced by a woman.

I remember when they tried to sell us that, thirty years ago culture was all WOMEN! HERE’S PLAYGIRL AND CHIPPENDALES!!!???

And so many women were so happy to have anything, something, that they dutifully bought Playgirl—hairy man laying across the centerfold, soft penis, ooooooh.

Groups of women, going to Chippendales, screaming, laughing hooting….

Anyway okay that’s one version of the female gaze that we have been offered:

“Hey ladies! Here’s your fuckin’ fireman calendar!” But it’s kinda –- naaaahhh. Pass. We don’t want that. NOT BUYING IT.

Transcript source: Soloway’s Topple Productions website.

Unfortunately for Soloway’s breezy narrative, at one point 2 million women were buying Playgirl every month, and readership only dropped in the wake of the conservatism of the 1980s (as did that of men’s adult magazines). If she was so quick to just write them all off as desperate, as well as fans of Magic Mike and the Chippendales, I don’t need to ask what she would make of Touch fans.

Was she unaware? Unlikely, given her expertise. Why then, would she make such insulting claims? Why did no-one in the Q&A call her out on them?

K-pop can be pretty bawdy sometimes, and that’s precisely why some fans like it. But ogling isn’t mutually exclusive with enjoying it for more ‘noble’ reasons, nor does it preclude other fans genuinely only liking it for the music. Source: lalalalyssaa

K-pop can be pretty bawdy sometimes, and that’s precisely why some fans like it. But ogling isn’t mutually exclusive with enjoying it for more ‘noble’ reasons, nor does it preclude other fans genuinely only liking it for the music. Source: lalalalyssaa

As a sometime guest lecturer myself (invite me to your campus!), I’m painfully aware of how presentations encourage overgeneralizations and hyperbole that speakers may regret later. Also, with the benefit of hindsight, her talk—much of which actually consists of the reading of a poem—is very much an example of the call to arms-type Female Gaze. So, I can completely understand the emotional reaction of the audience, and normally I’d very much give her the benefit of the doubt.

Not Soloway. Again, there’s her prominence to consider, and her ensuing position as the very first person many people listen to about the subject. There’s her own invitation to scrutinize her, by virtue of how earlier in that keynote address, she wasn’t shy about her hope that it would anchor her name to the female gazes, like Laura Mulvey’s is to the men’s. There’s the stream of consciousness-like feel to her talk that emerges from such scrutiny, so replete is it with bizarre, dubious claims, including such sophistry as “I mean, what is gang rape? It is men wanting to have sex in the same room as one another, but using [a slut] so they don’t have to name and own their own desire for each other.” But most of all, and ultimately the only reason I’m so focused on her instead of ignoring her entirely, there’s the fact that most other commentators on the female gazes generally agree with her that women don’t ogle or objectify—and share the utter bullshit she spouts about men’s gazes and sexuality that’s required to take that position.

I realize that’s quite a statement to leave you hanging on. My apologies. Those commentators will be covered in later posts. For now, I invite you to watch Soloway’s talk for yourself (or even better and quicker, the stark transcript), and ask you what actual evidence she presents for her many confident comments about “chismales.” Or, what proof Ellis provides for this one:

As a queer woman it might seem to any men who are attracted to women, that I would love images of half naked oiled up women, because they do. But while they may just see the object of their desire, I have to also see myself. So when I see sexualized women on screen who are given no agency, plot or power, I don’t get anything positive from that. It feels unbelievably naive and worrying that someone who is for all intents and purposes a pliant sexual object could be genuinely and maturely desirable.

Er…I don’t love images of half-naked oiled-up women. I didn’t when I was still a virgin. Alas, since then I’ve actually never encountered any half-naked, oiled-up women to help change my mind. (Sigh.) But my experience has taught me that a good grip is needed for most positions. That lotions, cosmetics, perfumes, and (within reason!) even showers can be a turn-off too, because they stop women feeling and smelling like women (yes, perish the thought—smell and touch can be important to men too). So, I’m going to take a wild guess that oiling women up wouldn’t help with either.

Image: ‘Effy in Beijing (for American Apparel),’ 2014, by Monika Mogi. Another example of the female gaze from Girl on Girl, but which inexplicably aligns exactly with my own tastes. Source: Maiden Noir.

Nor do I get anything positive from sexualized women on screen who are given no agency, plot, or power—my fetish is for the exact opposite. For sure, if I was single, and encountered a nubile and willing “pliant sexual object,” then I probably wouldn’t kick her out of bed. But I’d much prefer an assertive and confident woman who took some initiative—which is why I married one.

Do all cishet men share my tastes? Absolutely not. But I’d venture I know a hell of lot more about their desires than Ellis does. Because I’m a cishet man? Yes, of course, but absolutely not only. Rather, because I’ve actually asked other men about their tastes too. A lot. Whereas Ellis gives no indication of having asked so much as one.

Can you imagine what social media would do to me if I said something so crude and stereotypical? That fat wallets say, turned absolutely all women on—and without having asked even a single one of them?

I may have said a lot of controversial stuff so far, but nothing remotely as absurd or disingenuous. All I’ve said about women’s tastes specifically is that they like looking too, and even that—which shouldn’t even be controversial—has been based only on what women have said themselves. I’ve been very careful about that.

Why do Ellis and her colleagues not realize their own hypocrisy? Where does their confidence and certainly about what men want come from? Where, for that matter, does yours?

Photo by Mahrael Boutros from Pexels

What Does it Mean to Look, Exactly?

To make the revolutionary claim that women do ogle men and/or each other however, doesn’t necessarily mean they do so in the same ways as cishet men, or to the same degrees. For example, in 2015 Esther Yu, Editor in Chief of the feminist site Arco Collective, wrote in one of the rare more nuanced takes on the female gazes out there, that:

“…there are no ‘tits or ass’ for hetero women—no single feature on the male body that concentrates desire with as much intensity and density as the woman’s breast does for the hetero man. There are, of course, lots of sexually charged zones on men’s bodies, but it’s nearly impossible to point to a part of the anatomy that both excites desire and stands in as a marker of that desire as efficiently as the breast. Its presence means sex, even if any given instance of its image does not itself incite desire. It is culturally iconic—an icon of sex and of male sexual pleasure.

What women find sexy about men’s bodies is more diffuse. The hands, the naked back and chest, the eyes, and the forearm are all usual suspects. But men’s bodies don’t seem to be accessible for female desire in the same way. Even the penis doesn’t signify properly as a locus for female desire because it is at least as iconic of men’s sexual aggression as it is of the possibility for female pleasure.”

Indeed, in this series I’ll also discuss transmen’s and transwomen’s experiences of changing libidos, sexualities, and desires in their new bodies, which strongly suggest that these differences are fundamental. Still, let me say it again for those in the back—that there are differences between women and men, possibly big differences, that still doesn’t mean that women don’t ogle, a lot. Or wouldn’t ogle, were they not socially sanctioned for doing do.

Source: Know Your Meme.

Questions to Ask if Something Qualifies for the Female Gaze(s)

For understanding the female gazes, all these issues raised would seem to present quite the conundrum. They don’t, really. Queer fans of Touch, or other MVs like it, aren’t going to stop loving them simply because gatekeepers think they can’t or shouldn’t. That said, this series is about finding the female gazes. It’s about being proactive, not simply waiting around to hear whatever Twitter has to say about any given media text. Specifically, it’s about formulating a series of questions with which to judge if something is aimed at cishet women, queer women, or neither. By all means, if anyone who is neither a cishet woman or a queer woman makes a determination based on those questions, but members of those groups overwhelmingly decide otherwise, then that person should do a major rethink. But the point remains that anyone can ask those questions.

If that accessibility sounds like the height of cishet male privilege, then, again, I feel that’s more than a little hypocritical: over 99 percent of commenters on something being male-gazey identify as women, and no-one seems to have a problem with that. No, I’m not being defensive, you’re being defensive. And yes, there’s a lot more uncomfortable truths like that to come in this series. All for the sake of challenging what you and I thought we knew about male and female desire.

Did I say “finding” the female gazes though? I lie. I think I’ve already found the necessary questions, which really aren’t that complicated:

- Does the text present (wo)men in a sexualized manner?

- Does it present an authentic, believable (queer) relationship between characters, and/or “humanize” them?

- Is it produced by and/or explicitly for (queer) women?

I know—many of you may be already be ROTFL at the first. So let me clarify:

- The brackets are for the queer female gaze; without them they’re for the female gaze.

- The questions are in order of importance.

- The first question is a necessary condition to qualify for the female gazes. Certainly, as discussed, some commentators argue that the terms can just refer to sorely underrepresented, female ways of seeing the world in general (the Female Gaze) not just of other men or women in a sexual sense, and I greatly respect that. But consider that most people familiar with the term “male gaze” consider it to be nothing but sexual. So, not to also include a sexual component in the equivalent female concepts would be unnecessarily confusing and hypocritical. (And again, it is very telling about their notions of male and female sexuality that so many commentators are just fine with that.)

- “Sexualization” is a broad, amorphous term, and its manifestations are hardly confined to tight clothes, sexual poses, shirtless guys, and gratuitous skin. Any situation, body part, or object can be sexualized. This glance at 0:21 is. The reading of this note in Atonement was too. The smell of my wife. (You get the idea.) Touch, meanwhile, is sexualized in a “traditional” sense. But the infamous armpit scene in Lady on Fire is hardly subtle either, no matter how deep and meaningful is the relationship of the characters involved.

- But to claim sexualization is a necessary component of the gaze is not to claim that all those texts are equally queer. Nor that—let me nip this asinine notion in the bud immediately—pornography aimed at heterosexual men say, is somehow queer simply by virtue of sexualizing women. (Which is not to say that some lesbians can’t or don’t like some male-gazey heterosexual pornography.)

- These questions are only a guide!!

This series is about justifying those questions, exploring their implications, and finally applying them to Touch and other texts in the future. Part Two, which will hopefully up next week (but probably not frankly, considering this one took me two years!), will be about those many more claims that men are all about looks and women are all about feels, and why they’re wrong.

Until then, if I’m wrong about anything above, which is entirely possible for a cishet man writing about these subjects, then please do let me know!

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)