Estimated reading time: 6 minutes. Sources: Reiodori, LotteLiquor.

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes. Sources: Reiodori, LotteLiquor.

In the spirit of today’s title, let me direct you straight towards the moment I learned why Uemura Shōen was so amazing:

Shōen successfully turned her passion to creating a life worth living through her paintings. The themes and main subjects in all her paintings are women. Moreover, the women depicted in her paintings of this period are decisively different from those that appear in paintings done by men in the tradition of the Kyoto school of Bijinga, whose tradition dates back several hundred years. The major characteristic of women in the paintings before Shōen was that they were treated as the object of men’s sexual interest. Shōen painted working women for the first time in the history of Japanese painting. One of the masterpieces along that line is Yugure (Dusk). Here a middle-aged woman opens the paper-covered sliding door of her room to get enough light to thread a needle. Her plain kimono, the needlework, and the weak sunlight of the dusk impressively create an atmosphere of daily life. Japanese painting portrayed the reality of working women for the first time through Shōen’s works. They are as significant as the works of Millet, who painted working women instead of bourgeois women. In the late 1930s Uemura painted another middle-aged woman shown repapering a door to prepare for the coming winter in Banshu (Late Autumn). In another painting in a series titled Yuki no naka (In the Snow), she described women walking in the severe cold with heavy snow on their umbrellas. The clean, sharp, uncompromising lines of her drawing supported by her accurate drawing ability and the use of just a few colors clearly show the painter’s integrity of mind. It took Shōen a long time to reach this heightened state. Shōen received a great many awards for her noble and innovative art.

Page 71, “Three Women Artists of the Meiji Period (1868-1912): Reconsidering Their Significance from a Feminist Perspective” by Midori Wakakuwa (trans. by Naoko Aoki) in Japanese Women: New Feminist Perspectives on the Past, Present and Future ed. by Kumiko Fujimura-Fanselow and Atsuko Kameda (1995); my emphases.

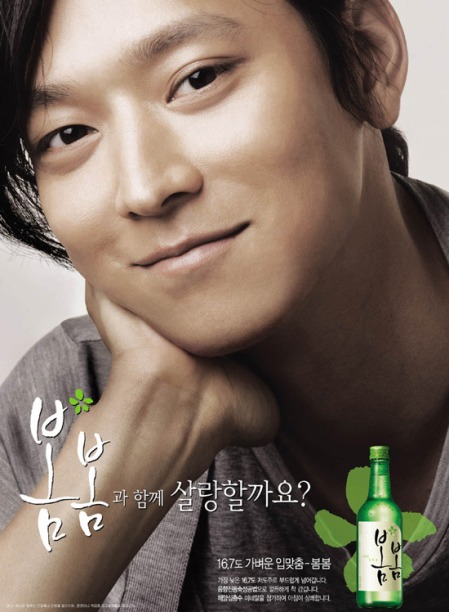

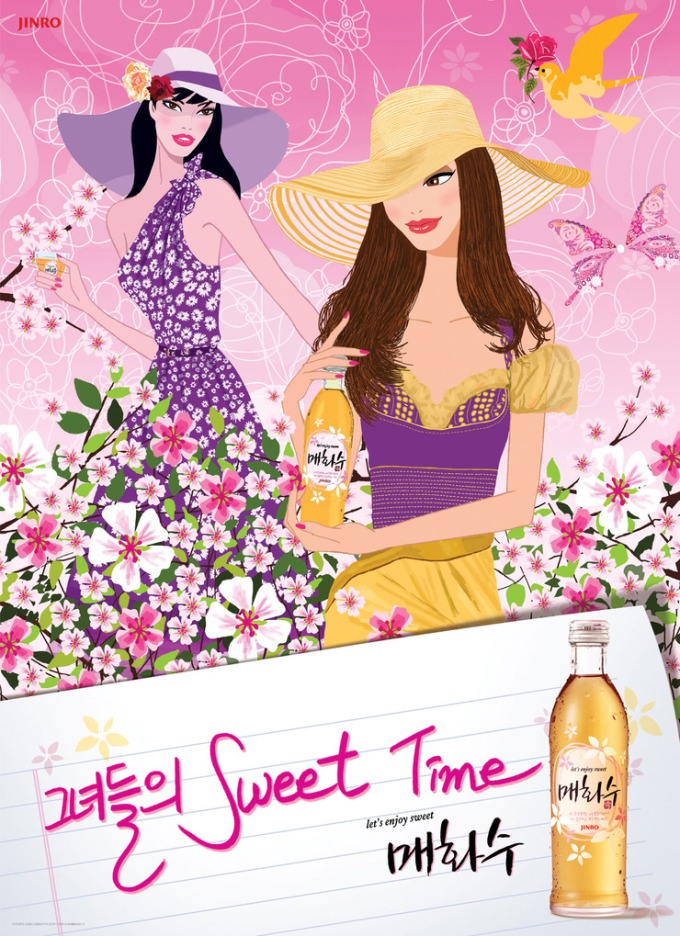

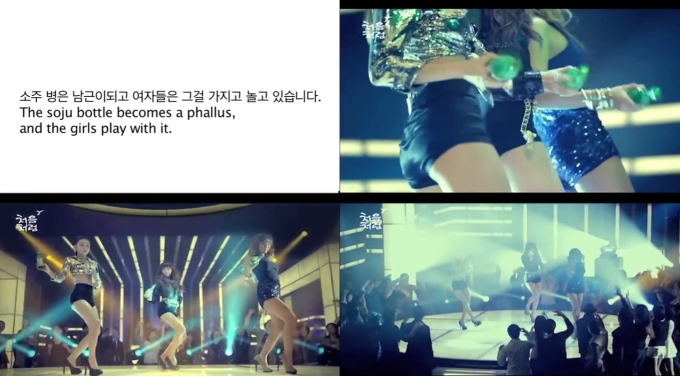

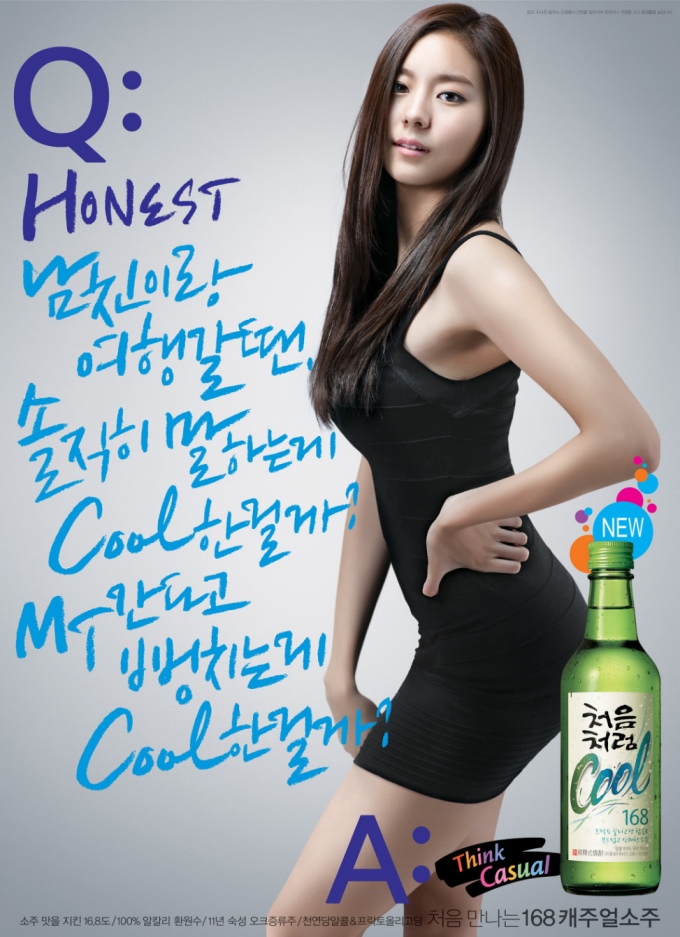

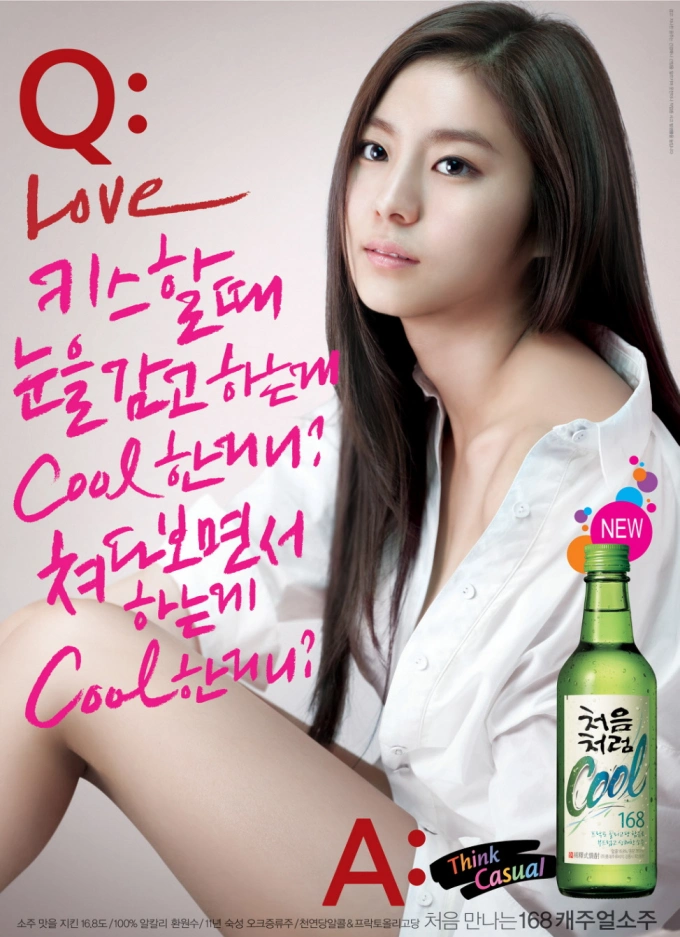

Which really did immediately remind me of modern rock singer Kim Yoon-ah‘s 2006 unique poster for Cheoeum-Cheoreom soju above. Like I wrote in 2010, and sadly still remains the case today, it’s “the only one I’ve seen in which the woman depicted is actually doing something of her own accord and enjoying herself, rather than waiting to be seduced by a man.” Which is not to say that sultry and seductive is bad in itself, but just a small sampling of soju posters over the years reveals how monotonous that theme can be, and how truly exceptional this soju poster is. Made more even more so, by the text in white at the bottom that I missed nine years ago (apologies for the poor quality):

It reads: “김윤아씨의 모델료는 가정폭력 피해자들에게 기부됩니다. 여성으로서 락음악의 새로운 가능성을 연 가수, 김윤아”/ “Kim Yun-Ah’s model fee is donated to domestic violence victims. Singer Kim Yoon-ah, who paved the way for new possibilities of rock music as a woman.”

Turning back to Uemura Shōen’s own depictions of women actually doing something, here are the paintings (and one from the In the Snow series) mentioned above by Wakakuwa:

At Dusk. Source: Japanese Painting Gallery

At Dusk. Source: Japanese Painting Gallery

Late Autumn. Source: Fine Art America.

Late Autumn. Source: Fine Art America.

Feathered Snow. Source: Japonica.

Feathered Snow. Source: Japonica.

I include the difficult to find full images, rather than the much more numerous, higher-quality close-ups of the women’s faces available, because of what I read about the importance of the paintings’ empty spaces at Japan Objects:

One of the most distinctive characteristics of Japanese painting when contrasted with its European counterpart is the use of empty space. And of course, this distinction was carried into the twentieth century….In Shōen Uemura’s Feathered Snow, the great blankness of the paper successful conveys the sensation of inclement weather, where the horizon reduces to edge of your umbrella as you try to shelter from the cold.

Inspiration aside though, I do wonder if the distinction between Shōen and her predecessors was as sharp as Wakakuwa suggests? In hindsight, her passage sounds a little hyperbolic. And my frustration with locating the full images among all those close-ups was a foreshadowing of what I’d read about Shōen online later, which tended to place her work very much on a continuum with other Bijinga (literally, “paintings of beautiful women”). That said, Jeff Hammond in The Japan Times notes her subjects weren’t the courtesans from the pleasure districts usually found in the genre. Also, in a must-read account in Japanonica of a 2017 exhibition of her work, historian and curator Roisin Inglesby finds subtle but important differences to works by her male contemporaries, despite her indeed very much sharing their emphasis on beauty:

…[Shōen’s] “outsider” status as a woman enabled her to acquire a deeper understanding of her female models and employ different approaches from male artists—a quality which, the curators argue, elevates her paintings by portraying women not just as objects created through the lens of the male gaze, but as thinking, feeling subjects who invite us to admire their inner beauty as well as their outward attractiveness.

In her efforts to show female beauty in what she believed to be its purest form, Shōen’s paintings are characterized by both a lightness of touch and a depth of feeling. [The tour guide] invited us to take time to look closely at the works and consider the emotional complexity beneath the peaceful expressions of Shōen’s subjects.

I wince at the crude characterization of the male gaze—admiration of outward attraction is not mutually exclusive with that of inner beauty—but that’s a subject for another post. Continuing later:

One of the most interesting aspects of [the] tour was [the] explanation of how Shōen gives agency to her subjects through a variety of techniques. In many paintings, she used a splash of red pigment on the women’s earlobes and fingertips to animate their otherwise placid demeanor. This small, yet visually enlivening, detail signals activity: these women hear; they touch. Often beautiful women are painted as objects of desire and admiration, yet through the composition of her work it seemed to me that Shōen invites her viewers to question their interior thoughts as well as appreciate their external beauty. The sparse background of Feathered Snow (1944) not only gives the impression of a punishing winter wind which beats its subjects back to one side of the painting, but encouraged my eyes to follow the movement of the composition and rest on their faces. What are they thinking as they trudge through the snow?

I recommend reading the article in full, and to watch this slideshow for many more examples of her work. Please feel free to add to (or correct) anything above also—including on Bijinga’s influence on Korean art, which I’m now about to look for more information about in my modest library, rather than preparing crucial PowerPoints for tomorrow’s classes. Damn you, Uemura! ;)

Related Posts:

- “Fucking is Fun!”: Sexual Innuendos in Vintage Korean Advertising

- Watching SPICA’s “Tonight” is an Awesome Teaching Moment About the Male Gaze. Here’s Why. (Part 1 of 3)

- Women’s Typical Poses in Advertisements: A Pain in the Neck?

- Shin Min-a Shows Us How to Pose Like a Woman

- Friday Fun? Korean Women Putting Shoes on Their Heads

- Beauties and the Beast? Understanding and Subverting the Male Gaze through Soju Advertisements

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)

But in fairness to Lee Hyori, Doosan was in the midst of reorganizing itself into a holding company centered around heavy industries when it hired her, and in hindsight the same company that had just bought

But in fairness to Lee Hyori, Doosan was in the midst of reorganizing itself into a holding company centered around heavy industries when it hired her, and in hindsight the same company that had just bought

(Source:

(Source:

3) Lee Myung-bak

3) Lee Myung-bak  8) Choi Han-bit (최한빛) on the right (

8) Choi Han-bit (최한빛) on the right (