(Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 12)

(Source: @niiaebi)

(Source: @niiaebi)

Did I tell you how much I love following Korean feminism on twitter? I’m completely addicted now. Add some sexual attraction to the buzz, thanks to my becoming acquainted with a self-professed loud and proud “fertile woman” (a.k.a. 나는 가임여성 이다/@niiaebi), and my body was all set to receive one powerful hit last week:

좆나 크리피하고 토악질나온다 무슨 재단사세요? 정육점 고기 품평하세요? 하 좆팔 김연아 선수는 외국에서 태어나셔야했다

“That [picture below] is so fucking creepy, I feel like throwing up. Are you a tailor or what? Are you judging her body parts like cuts of meat? Fucking hilarious. If only Kim Yuna* had been born in a foreign country. [Because they wouldn’t write about her like that there.]”

I know, right? If only I wasn’t already married. But she wasn’t finished yet:

진짜 국적이 죄다 국적이 죄야. 대체 왜 사람을 고기처럼 분석해놓는 거냐. 그리고 개쳐웃긴 점이 냄져몸은 ^절대^ 이렇게 상세히 나누고 재단하는 꼴 살면서 단 한번도 못봤음. 여성을 사람으로 안보고 인형으로 본단 걸 아주 당당하게 기사로 냈지요?

“It’s her nationality that is the real crime. Why on earth was she measured like meat? But the funniest thing is that I’ve never seen men’s bodies measured like this. Not even once in my life. The fact that this is from a news article clearly shows women are seen as dolls. Is the author proud of this article?”

I was so mesmerized, I  couldn’t have agreed more. But then I glanced again at the images of Kim Yuna skating, and suddenly sobered up: didn’t she retire 3 years ago?

couldn’t have agreed more. But then I glanced again at the images of Kim Yuna skating, and suddenly sobered up: didn’t she retire 3 years ago?

She did. It turned out, the left image came from a 7 year-old Chosun Ilbo article, which was also translated into English. And both are as vacuous as they are problematic. Rather than digging them up again, I began coquettishly tweeting back to @niiaebi, she should have burned them and buried the ashes. Lest they grow back again in the form of some mammoth blogpost somewhere.

Then I noticed that there was one crucial omission in the English translation, and it was too late.

Also, perhaps remembering that objects of your affection are not usually impressed if you have no opinion of your own and simply agree with everything they say, later I realized the articles weren’t problematic for the reasons @niiaebi mentioned, but were for exciting new ones that you will totally want to learn about.

I shouldn’t come on too strong though. So, let’s warm up to those with that omission first. It’s in the second paragraph:

서양인 못지않은 김연아의 ‘황금 몸매’의 가장 큰 특징은 긴 팔과 다리다. 1m64의 키에 체중 47㎏인 김연아의 하체 길이(허리~복사뼈)는 96㎝. 목 아래에서부터 허리까지 잰 상체 길이(50㎝)의 두 배에 가깝다. 패션 스타일리스트 김성일씨는 “일반인은 상·하체 비율이 4.5대 5.5만 돼도 다리가 긴 편에 속한다”며 “이렇게 다리가 긴 덕분에 똑같이 회전을 해도 회전이 크고 우아해 보이는 것”이라고 말했다.

In the English version:

Standing 164 cm tall and weighing 47 kg, Kim’s lower body from waist to the ankle bone measures 96 cm, almost double the length of her torso, which is 50 cm. Fashion stylist Kim Seong-il said, “With normal people, if the ratio of the upper and the lower body is 4.5:5.5, we consider them long-legged. Because of her long legs, Kim’s jumps look bigger and more elegant.”

It’s the first line that’s missing:

서양인 못지않은 김연아의 ‘황금 몸매’의 가장 큰 특징은 긴 팔과 다리다

“The most notable trait of her ‘golden [ratio] body’ is her long limbs, just like those of a Westerner’s.”

I admit that sounds pretty innocuous in itself. People use races and ethnicities as shorthand for body types and features all the time. In this case, author Jeong Sae-yeong is alluding to the common knowledge that Westerners are taller and have longer limbs than Koreans, and that Western women have larger breasts too.

But journalists shouldn’t be using such lazy stereotypes. This binary hinders more than it helps understanding, and can even lead to genuine harm.

For a start, because in practice “Westerners” usually only means “Caucasians.” Next, because Caucasians alone have a wide range of body types and sizes. Also, because even if the comparison was once broadly true, changes in Korean health and diets meant it was already out of date in 2010 (let alone in 2017).

Why do such obvious things need to be said? To someone purporting to explain bodies to us?

Continuing to position a fundamentally flawed representation of one race as the Occidental opposite of all Koreans though, does justify providing a very narrow range of small clothing sizes to the latter. It places the onus on consumers to fit their bodies to the clothes, rather than vice-versa.

This makes its absence in the English version of the article all the more glaring. Why did the anonymous translator not include it? Did they feel non-Koreans wouldn’t be interested? Did they feel embarrassed by it at all?

We can only speculate. But probably there is no grand conspiracy really: the same newspaper wasn’t shy in talking in terms of Western bodies in other English articles back then. It’s still depressingly common in the media today too. Alas, the very sexy quotes from Japanese sociologist Yoshio Sugimoto I planned to give, about the agendas of core subcultural groups dominating the mass media and intercultural-transactions, will have to wait for a more opportune time.

Yet the fact remains, English readers weren’t being given the full story. It’s something to chew on.

(Sources: left; right)

(Sources: left; right)

Moving on to the rest of the article and the image, to my surprise my issue with them was less with the fact that Kim Yuna’s body parts are presented like slabs of meat, as with ice-skating itself.

It’s all Camille Paglia’s fault:

Early on, I was in love with beauty. I don’t feel less because I’m in the presence of a beautiful person. I don’t go [imitates crying and dabbing tears], “Oh, I’ll never be that beautiful!” What a ridiculous attitude to take!–the Naomi Wolf attitude. When men look at sports, when they look at football, they don’t go [crying], “Oh, I’ll never be that fast, I’ll never be that strong!” When people look at Michelangelo’s David, do they commit suicide? No. See what I mean? When you see a strong person, a fast person, you go, “Wow! That is fabulous.” When you see a beautiful person: “How beautiful.” That’s what I’m bringing back to feminism. You go, “What a beautiful person, what a beautiful man, what a beautiful woman, what beautiful hair, what beautiful boobs!” Okay, now I’ll be charged with sexual harassment, probably. I won’t even be able to get out of the room!

We should not have to apologize for reveling in beauty. It is not a trick invented by nasty men in a room someplace on Madison Avenue….It is so provincial, feminism’s problem with beauty. We have got to get over this.

(Sex, Art, and American Culture: Essays by Camille Paglia {1992}, pp.264-5; my emphases in bold.)

Which I take to mean that it is okay to exalt in magnificent bodies, whether for their looks, athletic prowess, or any number of reasons. It is okay to be curious about what it is exactly that sets them apart from everyone else in those regards, and to try to quantify that. So, when Jeong Sae-yeong writes (in the translation) that because “of [Yuna’s] long legs, Kim’s jumps look bigger and more elegant”, that because her arms are very long her “small arm movements look softer and more fluid”, and that “overdevelopment of muscles in certain parts of the body such as upper arms or thighs can make movements look stiff”? And when those certain parts of the body are all sized up in the graphic?

Then so what?

It pains me to say that, but, for all I know, those are all core tenets of figure-skating, and in that sense are no different to observing that, say, you need to be tall to play basketball well. If so, I can certainly disagree with those tenets and the values enshrined in them—short, toned people can’t help but be stiff and inelegant on the rink?—and I can strongly dislike figure-skating for that reason (and also because I believe anything entirely reliant on subjective, corruptible judging can’t possibly be considered a sport). But the point remains that athletes will always be sized up like this. It’s human nature.

Indeed, as @lsjkhj0903 points out in a reply to @niiaebi, it’s done to male athletes too:

초멘나사이합니다..비슷하게 남자도 있더라구요…

“It is similar with men too…”

(Source: @lsjkhj0903)

(Source: @lsjkhj0903)

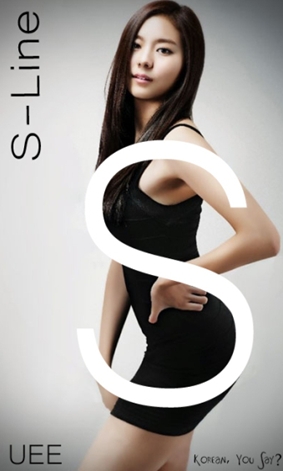

What many of you will have already noticed though, is that the graphic doesn’t just give a basic run-down of the lengths her long limbs. As pointed out in a reply by @lifejogipogi:

이건 정도의 차이가 너무 다르네요 김연아 선수는 ‘s라인’ ‘황금몸매’ 등 주관적인 평가가 한가득 들어있고 몸매 평가위주예요 김요한 선수 사진은 사무적이고 데이터의 일종 같은데 김연아 선수 사진은 가십거리 같네요

“No they are very different. The one with Kim Yuna is full of subjective comments, saying she has an ‘S-line’ and a ‘golden body figure’, and it is definitely about evaluating her body. Kim Yuhan’s case is more objective, and more like simple data. Yuna Kim’s photo just looks like a tabloid article.”

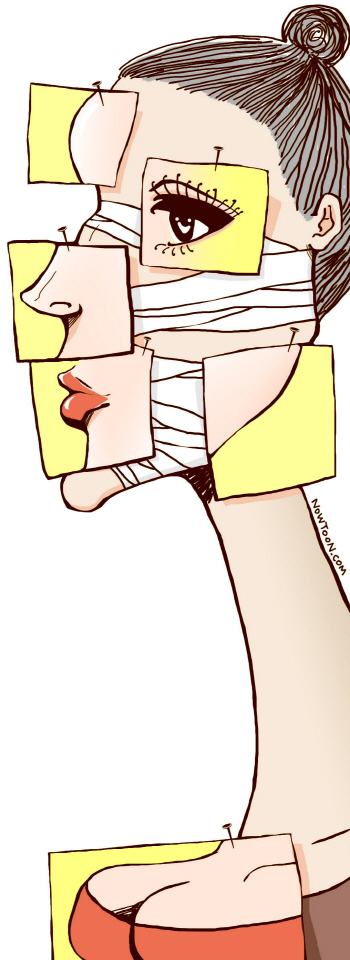

It also provides her bust size, the implication being that only those within a very narrow range can be elegant. Which is absurd, as is finding significance in instances of the golden ratio in the human body. So too with her “well-balanced” waist and silhouette (you have to wonder why the rest of us don’t topple over), as discussed in the article. Which concludes:

Fashion stylist Han Hye-yeon said, “Unlike many other athletes, Kim has a slender, flexible body, so she has the natural ‘S’ curve when she’s performing.” Kim So-yeon, an executive at a modeling agency, said, “She has perfect body proportions for a fashion model.”

That is not okay. It’s quite a leap from discussing athlete’s bodies’ suitability for ice-skating, to positioning Kim Yuna as standard-bearer of a body image ideal for everyone else. Particularly when she’s been hawking diet and beauty-related products for her entire career.

(Source: YouTube)

(Source: YouTube)

I don’t bemoan her for that necessarily, as it’s a rare female celebrity in Korea that has the luxury of being able to say no to advertising offers; although she’s certainly rich enough to reject them now, especially those that make dubious links to their products and her athletic prowess. I’ve also recently learned from reading Autumn Whitefield-Modrano’s new book Face Value: The Hidden Ways Beauty Shapes Women’s Lives (2016) about how having very specific statistics for the “perfect” body can even be liberating, in the sense that once you realize you can’t have something, you free yourself from trying (like with my accepting my being bald for instance, which I learned from a friend who’d accepted her own small breasts.)

I remain really struck though, at how this whole notion of ever obtaining such a specific combination of such perfect vital statistics so closely resembles that of a competition in the United States 100 years ago, fought over which college’s female students most closely resembled the Venus de Milo. Tens of thousands of women would be measured for it, and some women would come very close, even filing lawsuits to gain official recognition. But, crucially, none were ever universally accepted as the one and only, 20th century Venus de Milo. Because it’s almost like they were set to fail from the start:

The ridiculous thing about all this—well, one of the ridiculous things—is that these [measurements of women that came close] varied from one another by several inches. Not only that, but they were being compared to different standards, for there were multiple versions of the Venus de Milo’s measurements. Some physical culture practitioners quoted the statue’s bust-waist-hip stats as 39-26-38, while others believed she measured in at 34.75-28.5-36. The only stat everyone could agree on was the Venus de Milo’s height, which was set at 5-foot-4….

…times were changing anyhow—the flapper fashions newly in vogue looked best on tall, slender figures, and the Venus de Milo was starting to look a little too plump. In April 1923, the New York Times introduced the world to the “new Venus, whose proportions have been reduced by the athletic tendencies of the modern girl.” To be a true American modern Venus, women now “must be 5 feet 7 inches in height, a perfect 34, with 22-inch waist and 34-inch hips.” Furthermore, “[t]he ankle should measure 8 inches and the weight not exceed 110 pounds.”

And just like that, the beauty rules changed again. After decades of searching and dozens of contenders, America hadn’t found its perfect living, breathing reincarnation of Venus—because she didn’t, and couldn’t, exist.

Likewise, if they’re no longer presented in terms of their utility for her sport, then what is the purpose of providing Kim Yuna’s vital statistics, which is a combination that only she can ever have?

What else, but to remind women that their own bodies suck, and that they will probably die alone if they don’t at least try?

♥

* For those of you that don’t know: “Kim Yuna” does read like “Kim Yoona” in English, but it’s a misspelling. Her Korean name, “김연아,” should be spelt “Kim Yeon-a,” and it actually sounds like “Kim Yon-a,” with the “on” in “yon” pronounced like the “on” in “on/off.”

The Revealing the Korean Body Politic series:

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic Part 12: If You Don’t Have Kim Yuna’s Vital Statistics, Your Body Sucks and You Will Totally Die Alone

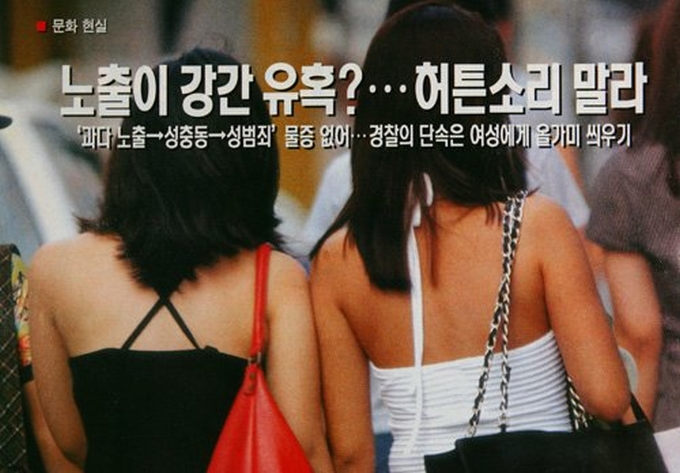

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 11: 노출이 강간 유혹?…허튼소리 말라 Wearing Revealing Clothes Leads to Rape? Don’t Be Absurd

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 10: “An epic battle between feminism and deep-seated misogyny is under way in South Korea”

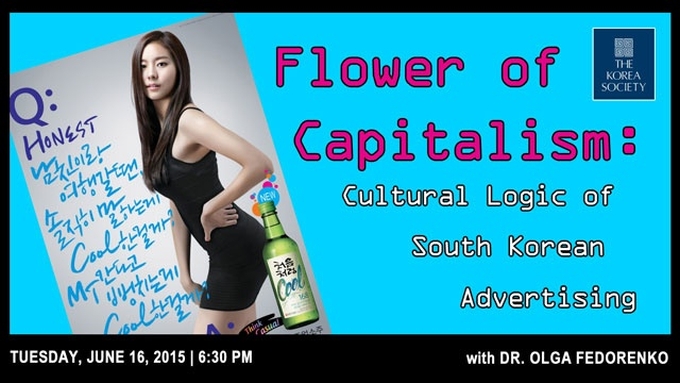

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 9: To Understand Modern Korean Misogyny, Look to the Modern Girls of the 1930s

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 8: The Bare-leg Bars of 1942

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 7: Keeping abreast of Korean bodylines

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 6: What is the REAL reason for the backlash?

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 5: Links

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 4: Girls are different from boys

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 3: Historical precedents for Korea’s modern beauty myth

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 2: Kwak Hyun-hwa (곽현화), Pin-up Grrrls, and The Banality of Sex and Nudity in the Media

- Bikinis, Breasts, and Backlash: Revealing the Korean Body Politic in 2012

same mistake myself, he probably makes few converts among Korean comedy fans with his sweeping denunciations of the entire genre. (Edit: In fairness, it’s more of an op-ed than an article really.)

same mistake myself, he probably makes few converts among Korean comedy fans with his sweeping denunciations of the entire genre. (Edit: In fairness, it’s more of an op-ed than an article really.)