“I believe in equality and love the Free the Nipple movement. After four years in Korea, I am still intrigued by its thirst for modernity mixed with its fear of losing its cultural past, sometimes to the point of schizophrenia.”

And with that self-introduction, how could I not accept Manouchka Elefant’s proposed guest post?

As well as being a long-time reader, she’s also a Swiss recipient of the NIIED scholarship, and has just completed her Master’s in finance at Yonsei University (see here for her LinkedIn bio). She adds:

“Anyways, a few friends read my paper [for my Modern Korean Society & Culture class] and found it very interesting and suggested I publish it. Since your blog is my reference on the subject I thought I’d send it to you.”

Flattery will get readers everywhere. So, without any further ado, let me present her post:

Introduction

Women in Korea have come a long way since the beginning of the century. They have more freedom, greater access to education, and higher spending power thanks to their increasing participation in the workforce. This emancipation of women has been accompanied by a seemingly paradoxical phenomenon: the explosion of the beauty industry and in particular the normalization of plastic surgery procedures. Per capita, South Korea is the number one country for non-invasive and invasive plastic surgery performed and counts the highest number of plastic surgeons (Raitt 2014). The peninsula’s history and Confucian heritage has a tremendous impact on women’s growth in society as well as on contemporary beauty ideals. Today cosmetic surgery can be seen as the two sides of a same coin, it is both an appropriation of one’s body and conformation to society’s expectations of women in Korea.

Historical heritage

Analyzing womanhood in Korea requires us to understand the country’s Confucian heritage and its revolutions. Typically, the contemporary obsession for beauty in Korea is seen as “conformity to patriarchal version of femininity in order to maximize women’s chances of success in marriage and the economy” (Ruth Holliday 2012). However, in a relatively short period, the Confucian ideal has gone through a lot of transformations, notably in the 1930’s and after the Japanese occupation.

Confucian Ideal

Confucian scholars would be quite surprised to see that Korean people no longer appreciate women with beautiful moon faces. In their time, “virtuous femininity” meant that upper class women conformed to an exacting Confucian decorum (Ruth Holliday 2012). Whether a wife, mother, or daughter, a woman’s self was fully dependent on that of men. They were restricted to the domestic sphere, and their success was in their “ability to mimic a concealed and deferential ideal, defined by virginity or maternity” (Ruth Holliday 2012). Chastity and modesty were highly valued and expected of women from a young age (Lee 2014). To some extent, Korean women are still expected to portray an image of innocence and modesty no matter their age.

Also inherited from the Choson dynasty is the concept of embodying one’s social class through one’s appearance, with the “practice of displaying social status through class-appropriate clothing and decorum, and the ways in which they are interpolated in neoliberal discourses of self-improvement and class mobility are evident in the ways in which cosmopolitan subjectivity is embodied through cosmetic surgery as a sign of a desired class, social or gendered identity” (Elfving-Hwang 2013), leading to one of the theories behind cosmetic surgery as a way to achieve social class identity, which seems to be only part of the phenomenon.

Modern Girl

The 1920-1930’s with its fun flapper girls in the West, dancing to jazz and smoking were in stark contrasts to the Confucian doctrine, yet this new “modern girl” had a strong impact on Korean women and their  aspiration to emancipate themselves from constraining paternalism (appendix 1, source: Gusts of Popular Feeling; rather than in the original separate appendix, I’ve posted images and tables as they came up—James). The modern girl’s short hair was in direct clash with Confucian values and was seen by many as a sexual revolution (Chung 2012). However, the modern girl was associated to decadence, bourgeoisie, and conspicuous consumption. “A woman drawing attention to her own sexuality – body and desire- was frowned upon in traditional Korea” and the modern girl came to symbolize more than women’s freedom, but also the “fracturing of class [poor versus bourgeois] and citizenship [Korean versus Japanese]” (Chung 2012).

aspiration to emancipate themselves from constraining paternalism (appendix 1, source: Gusts of Popular Feeling; rather than in the original separate appendix, I’ve posted images and tables as they came up—James). The modern girl’s short hair was in direct clash with Confucian values and was seen by many as a sexual revolution (Chung 2012). However, the modern girl was associated to decadence, bourgeoisie, and conspicuous consumption. “A woman drawing attention to her own sexuality – body and desire- was frowned upon in traditional Korea” and the modern girl came to symbolize more than women’s freedom, but also the “fracturing of class [poor versus bourgeois] and citizenship [Korean versus Japanese]” (Chung 2012).

Furthermore, the modern girl was not a mere imitation of Japanese or American influences, it went deeper than hair and clothes, “it mirrored the changing social consciousness, the collective identity of traditional womanhood as an aspect of modernity and modern conditions in colonial Korea” (Chung 2012).

Additionally, the modern girl “challenged the traditional gender roles and centuries of Confucian morality by accumulating products that enhanced female beauty and sexuality” (Chung 2012), which also meant that one was able to alter their appearance and other’s perception of them through consumption. We can wonder if it was a precursor to contemporary Korea’s constant availability of cosmetics and clothing shops.

However, in the context of occupied Korea, the modern girl was highly criticized for being influenced by the Japanese media and to some extent for supporting the colonial agenda. It was seen as another way in which Japan attempted to impose itself as a modernizer over Korea and that “the modern girl phenomenon evolved in the framework of this cultural and economic subordination of the era, which led to its conflicting popular reception” (Chung 2012). Paradoxically, people were attracted to this new image of femininity, spurring their “voyeuristic participation in mass culture, titillating the public while inviting condemnation at the same time” (Chung 2012). It can be similarly observed with today’s pop-culture idols, with the public simultaneously attracted by these sophisticated girl bands while criticizing their over-sexualized image.

Wise Mother Good Wife

At the other end of the spectrum is the ideal of wise mother good wife and although it also served to empower women, its motivations were quite distinct from the modern girl. This concept was at the complicated “intersections of patriarchy, colonialism, nationalism, and western modernity” under which women followed, fought back, or appropriated the predominant male dominated world (Choi 2009).

The wise mother good wife ideology was used by different groups, each with its agenda. Korean nationalists reinforced the role of mothers as educators of Korean children and as supporters for their husbands. Japan’s gender program used it both at home and in colonial Korea “with the aim of producing obedient imperial subjects and an efficient, submissive workforce” (Choi 2009), while protestant missionaries saw it as a way to spread their faith with a “pious mother and wife as a moral guide in the Christian family” (Choi 2009). All of this contributed to the education of women in Korea.

This ideology was deeply rooted in a patrilineal social structure, promoting chastity, marriage and motherhood. It was in direct clash with the modern girl, which was highly criticized for her vanity, her consumption, and her relatively open sexuality. Nevertheless, wise mother good wife also served as a platform to empower women, even if within a restricted domain. The women who “benefited from this education centered in domesticity paved the way to new domains for career women” (Choi 2009). Women were however, not educated for their own benefit and advancement as individual beings, but rather for what they brought to men and society, therefore not for their emancipation. Nonetheless, it set the path towards higher education and more freedom for Korean women.

Women’s Growth in Korean Society

Women’s Education

As we saw, there were several different movements promoting women’s education in Korea, from the protestant missionaries to the Japanese regime. However, some Confucian scholars, influenced by the West, also associated the advancement of women as a sign of a modernized society. They thought that “woman is the foundation of human society and the girder of the house and thus if she is weak or ignorant, she would not be able to fulfill her central role” (Choi 2009).

With Korea’s independence and its efforts towards development, education became widely available to both genders. Educating women therefore was modernizing Korean society, as well as increasing the  workforces’ overall education level to achieve economic development. In 1966, only 33% of girls went from elementary school to middle school. Similarly, 20% continued to high school and 4% to university. However, by 1998, 61.6% went from middle school to high school and 61.6% to university (Korean Overseas Information Service n.d.). By 2006, the number of women reaching higher education was as high as that of men, with 81.1% and 82.9% respectively entering college and university (table 1) (Ou-Byung Chae 2008).

workforces’ overall education level to achieve economic development. In 1966, only 33% of girls went from elementary school to middle school. Similarly, 20% continued to high school and 4% to university. However, by 1998, 61.6% went from middle school to high school and 61.6% to university (Korean Overseas Information Service n.d.). By 2006, the number of women reaching higher education was as high as that of men, with 81.1% and 82.9% respectively entering college and university (table 1) (Ou-Byung Chae 2008).

This remarkable progress in the number of women achieving higher education also came with its own challenges. Although women achieve higher education there is still a strong gender bias both in the educational curriculum, in the family sphere, and in the workplace.

Women’s Employment

Today, Korea is known for its high educational standards but also for the high inequalities between men and women in the workplace. Last years’ World Economic Forum ranked Korea 111th out of 136 nations in its Global Gender Gap report. While in 2012, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) pay gap report placed Korea in the top of the list with a 39% differences between men and women’s pay (McKay 2014).

Although women have made a lot of progress in Korea’s work environment, according to Statistics Korea’s latest figures, they still only participate for about 50% in the workforce, whereas men reach over 73% participation. Furthermore, the market research firm CEOScore found that in 2013 about 1 out of 1,430 employed women reached a corporate management job against 1 out of every 90 men (McKay 2014). On top of it, Korea also shows the poorest level of female graduate employment among the OECD countries (McKay 2014).

Granting the Korean government has made it part of its objectives to change the situation, a number of factors create this tense work environment for women. It is commonly perceived that women in Korea suffer from higher job discrimination, starting from the hiring process all the way to corporate advancement. The Korean work culture and social expectations of gender roles both have an important effect. High unemployment further reduces women’s chances of finding good jobs, with the economy feeling global pressures and a staggering number of overqualified job hunters, women are often passed over for men in an environment where youth unemployment has been around 8% since 2010 (Park 2014). Both women and men, see being good looking as the next level to compete in the job market and “employment cosmetic surgery” is growing in popularity with both genders (Korean Overseas Information Service n.d.).

Furthermore, preconception of women’s gender roles as mothers and wives results in discrimination in the workplace. The government’s policies to increase women’s participation in the workforce are not “working well because companies still view men and women’s societal duties as different” (McKay 2014). Additionally, the prevalent perception that women are supposed to quit working after getting married to focus on raising children means that “women are being forced to choose between having a career or having a family” (McKay 2014). Very few women go back to work after having had children in Korea, not necessarily by choice. During recruiting, a lot of companies prefer male recruits over young women, apprehensive at the prospect of them getting pregnant (maternity leave cost). As a result, a lot of women choose to delay having a family (Lee 2014).

Breaking the glass ceiling is particularly difficult, with a male dominated work culture. After-work bonding, involving copious amount of alcohol, can improve work relationships and even impact promotions. However, these are not widely considered as appropriate for women, especially if they have children, and whom often don’t want to drink as much as their male colleagues. With numerous reports of male colleagues using alcoholic intoxication as an excuse for sexual harassment, it also puts women in a vulnerable position. Of reported workplace sexual harassment 44.5% of them happened at a hoesik (McKay 2014).

Additionally, there is a strong form of blatant sexism in the workplace. Taking the form of pressure against women not to take roles with responsibilities, to their abilities being questioned on the basis of their gender. Today’s sexism “arises from […] subordination for male authority, especially in the current capitalist environment where women are gradually gaining influence” to the point that some men feel threatened by women taking jobs they consider as being theirs (Lee 2014). Even more, “powerful women are facing negative sentiment among people in general” (Lee 2014).

On top of it all, women are expected to be feminine and complacent, to conform to social expectations (Lee 2014). In Korea, this usually means conforming to the rigid code of beauty.

The Female Ideal of Beauty

In all cultures and societies, beauty norms and representations are not frozen in time, but are constantly changing. The place of women in society has a very strong impact on what is deemed appropriate for their appearance. “Historically, Korea is a nation founded on Confucianism that places women at the bottom of the hierarchy and that treats women as inferior to men” (Lee 2014). Furthermore, Korea seems to be special in the way that the traditional model of beauty from the Choseon era lasted a long time without drastic changes until the country opened up to external influences (voluntarily and involuntarily) and at which point it was completely transformed. During the colonial period new beauty ideals started to emerge, but it is from the 1960’s on that a beauty revolution took place and accelerated with the country’s development.

Korean Beauty Standards

With the rapid transformation of Korea from a rural economy to a developed one, the role of women in society tremendously changed and with it the norms and customs of beauty. Looking back at pictures from the first part of the 20th century (appendix 2, below), we can see women with round faces, often with a center part in their hair. For many centuries, thick glossy hair, fair skin, thin eyebrows and small lips were the symbols of beauty. Make-up was often home-made from spices and plants and used minimally to enhance features. It was only acceptable for entertainment ladies to wear white powder or colorful products. In the 1930’s the Korean garb still was the norm and only very wealthy women would occasionally wear western clothing. Since the Choseon period (1392-1919) a simple yet elegant appearance, associated with a dignified behavior and humble manners, were considered the quintessence of beauty and elegance following Confucian standards. However, as the country suffered from poverty, most women did not have the means to spend on their appearance, only wealthy women could. Western fashions were for the wealthy and city folks while the average person still wore traditional clothes. “Korea was not a strong country, and people’s efforts to protect and preserve their identity served to strengthen their conservative values” (Lee 2014), which also translated in the way they portrayed themselves. This shifted slowly until the 1980s when Korean clothes started being reserved for special occasions and western fashion became the norm.

(Appendix 2, L-R: Portrait of four women, Peng Yang, Korea, 1924; Bride, Gishu, Korea, 1926; A young ‘kisaeng’ in full Korean traditional dress, ca. 1904. Source: University of Southern California Library)

(Appendix 2, L-R: Portrait of four women, Peng Yang, Korea, 1924; Bride, Gishu, Korea, 1926; A young ‘kisaeng’ in full Korean traditional dress, ca. 1904. Source: University of Southern California Library)

After the war, Korea opened up further to western culture, which became synonymous with development and modernity. Until the 1987 Democracy Movement “Confucian tradition was largely responsible for dictating the roles of women” (Lee 2014) and with it the way they should present themselves in society, but  this new era transformed both the role of women, bringing them from the home to the workplace, and the perception of beauty. “Under consumer capitalism Korean women’s bodies have entered the public sphere, no longer hidden away but now available for scrutiny and consumption” (Ruth Holliday 2012).

this new era transformed both the role of women, bringing them from the home to the workplace, and the perception of beauty. “Under consumer capitalism Korean women’s bodies have entered the public sphere, no longer hidden away but now available for scrutiny and consumption” (Ruth Holliday 2012).

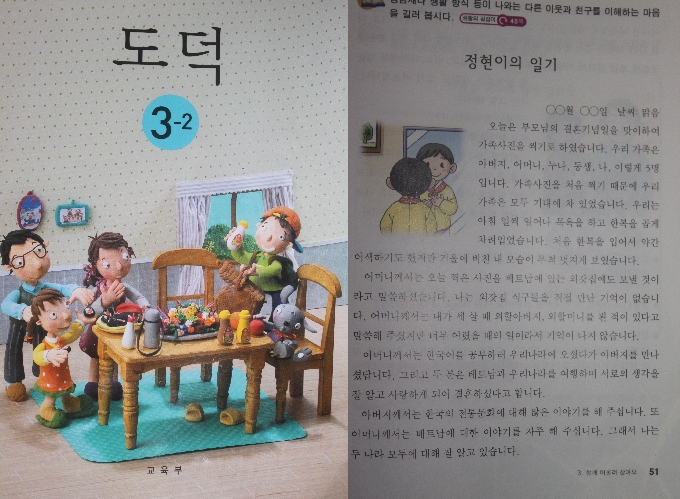

In Korea, there is tremendous pressure on women to conform, and most women are conscious of the “harsh criticism that comes when [they] deviate from the norm” (Lee 2014), leading to a strictly defined beauty ideal. The contemporary beauty ideal is quite far from the prevalent model of only 20 years ago. Nowadays, the Korean ideal of beauty looks nothing like the moon-shaped beauties of the past. Fair skin is still admired, but beautiful features are singularly different than in the past. Eyes should be big and open, the bridge of the nose should be high and its tip slender, the face should be small with a narrow jaw, the body should be very slight yet show an “S” shaped curves (appendix 3, source: The Grand Narrative). To some extent, this new ideal looks more like a comic book character than a realistic image of women, and can rarely be achieved without constraining one’s body or altering it drastically through cosmetic procedures. Yet it is omnipresent in the media, advertising, and in the messages directed to children from an early age (appendix 4).

(Appendix 4: Messages directed to young children carry messages of beauty, physiognomy and conformity, here in an advertisement for bean paste. Source: The Grand Narrative)

(Appendix 4: Messages directed to young children carry messages of beauty, physiognomy and conformity, here in an advertisement for bean paste. Source: The Grand Narrative)

This standardization of beauty is especially strong among young women who want to emulate celebrities and are constantly being reminded by the media and society that showing good care for one’s appearance is essential for achieving a good marriage and a successful life. The popularity of cosmetic surgery is such that it is considered normal for celebrities to be redone and still represent role models. It is hence no wonder that Korea is the countries with the highest number of children having plastic surgery and double eyelid surgery is a common gift for graduation from parents.

The paradox goes even further, asking women to embody simultaneously images of innocence and purity, while being glamourous and exciting to the male gaze. However, “expressions of sexual subjectivity remain a big taboo in Korea” where we “can have a 25 year-old’s S-line quite literally highlighted for a heterosexual male gaze, but heaven forbid she admit to having sexual feelings and experience herself” (Turnbull 2012).

Standardization of beauty is also spread through the assignment of different letters to exemplify the ideal shape, “while this practice is seemingly frivolous on the surface, it actually belies much more pernicious trends in society at large, when you have celebrities vocally espousing their alphabet-lines and therefore actually objectifying themselves as a conglomeration of “perfect” body parts rather than as whole, genuine people” (Turnbull 2013).

Fueling the Korean cosmetic industry’s steady growth of more than 10% per year for the last few years, the beauty obsession is constant, from adds for plastic surgery and dieting in public transportation to the “mushrooming cosmetic shops, which have increased 37% a year on average” (Raitt 2014). In a patriarchal society where women are not yet treated as equals, these all reinforce the belief that “pretty girls are more valuable” (Lee 2014) and push for conformity. It is a new way to impose the demure Confucian-influenced image that is wanted and anticipated of women.

Conforming to the Ideal

Some researchers assign plastic surgery in the “Neo-Confucian ‘culture of conformity’, where the unity of the whole is more important than the individuality of the one, producing beauty as a new requirement of decorum’ for women” leading to an environment where women are “obsessed with their appearance” (Ruth Holliday 2012).

Furthermore, the backlash in Korea can be very strong and according to scholar Lee Sang-Wha three factors have “helped uphold Korean society and eventually led to the demure girl image of today: gender segregation, division of gender-assigned labor and the subordination of women” (Lee 2014). It left no place for feminism in Korea’s Confucian heritage where the old values still push them to “appear subordinate and innocent” (Lee 2014).

However, important changes in Korean society can offer another reason behind contemporary beauty trends. The political and economic transformations of the past 30 years, accompanied by an incredible speed of democratization and industrialization, offered new social opportunities for women. As we have seen earlier, university attendance is extremely high, and Korea actually has one of the highest rate for women’s enrollment in college globally according to the OECD. Some sociologists argue that this “recent upsurge in female societal empowerment may be associated with an oppressive backlash in media portrayals of gender ideals” (Turnbull 2013). This unrealistic expectation on women has also been observed in other regions and “historical data suggest that societal shifts toward gender equality are often accompanied by increased media portrayal of unrealistic gender norms as a reactive “tool of oppression” by mainstream society” (Turnbull 2013) further pressuring women to conform to the beauty ideal.

All of these negative forces appear in the private and the public spheres. The “care of self and cosmetic surgery increasingly link notions of ‘correct’ or ‘appropriate’ appearance with performing adequately in society as a social subject” (Elfving-Hwang 2013).

Plastic Surgery’s Normalization

The numbers speak for themselves, the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons’ global ranking places Korea number one in procedures per capita in 2010 (table 2, below), ahead of the United States and Brazil, and also tops the list with the biggest number of registered cosmetic surgeons per capita (Elfving-Hwang 2013). According to the Korean Association for Plastic Surgery, “1 in every 77 people in South Korea has had [at least one] plastic surgery (Raitt 2014). The Fair Trade Commission also stated that one quarter of the world’s plastic surgeries take place in Korea, representing a 500 billion won industry (Raitt 2014).

There are two categories of cosmetic procedures. For the non-surgical procedures, the most popular ones are in order of importance: Botox, hyaluronic acid injectables, laser hair removal, autologous fat injectables, and IPL laser treatments (Raitt 2014). These petite surgeries are highly popular as they are non-invasive, cheaper, and require no down-time, exemplified by Botox which counted 145,688 procedures in 2012. On the other hand, the surgical procedures in order of popularity are: lipoplasty, breast augmentation, rhinoplasty, blepharoplasty (double eyelid), and abdominalplasty (table 3, source: source: the Korean Consumer Agency).

There are two categories of cosmetic procedures. For the non-surgical procedures, the most popular ones are in order of importance: Botox, hyaluronic acid injectables, laser hair removal, autologous fat injectables, and IPL laser treatments (Raitt 2014). These petite surgeries are highly popular as they are non-invasive, cheaper, and require no down-time, exemplified by Botox which counted 145,688 procedures in 2012. On the other hand, the surgical procedures in order of popularity are: lipoplasty, breast augmentation, rhinoplasty, blepharoplasty (double eyelid), and abdominalplasty (table 3, source: source: the Korean Consumer Agency).

As shown by these statistics, plastic surgery in Korea is increasingly normal, with more and more women, and men too, opting to go under the knife. However it is important to point out that women are not passive consumers of beauty, on the contrary they are “highly informed, active agents in their engagements with cosmetic surgeons” (Ruth Holliday 2012). Cosmetic surgery is seen as something positive, that enables access to a desired social status and becomes a symbol of middle class and gendered identity (Elfving-Hwang 2013). Furthermore, the liberalization of cosmetic surgery is also seen as “democratizing practice” and the high growth rate of complex surgeries with high risks, such as the chin and mandibular reduction operation, reflect the trivialization of the practice (Elfving-Hwang 2013).

As shown by these statistics, plastic surgery in Korea is increasingly normal, with more and more women, and men too, opting to go under the knife. However it is important to point out that women are not passive consumers of beauty, on the contrary they are “highly informed, active agents in their engagements with cosmetic surgeons” (Ruth Holliday 2012). Cosmetic surgery is seen as something positive, that enables access to a desired social status and becomes a symbol of middle class and gendered identity (Elfving-Hwang 2013). Furthermore, the liberalization of cosmetic surgery is also seen as “democratizing practice” and the high growth rate of complex surgeries with high risks, such as the chin and mandibular reduction operation, reflect the trivialization of the practice (Elfving-Hwang 2013).

Confirming earlier arguments about the culture of appearance, plastic surgery has become a marker of consumer middle class identity, of wealth and social status. In turn it “emerges as a highly effective force encouraging individuals to perceive aesthetic surgical intervention as a practical and normative option for self-improvement” (Elfving-Hwang 2013). However, it carries an important weight as well, creating an internalization of patriarchal beauty standards, where “women constantly examine their bodies in a negative and pathological light” (Ruth Holliday 2012) in their insatiable quest to an unrealistic body image.

Conclusion

Women’s place in Korean society, their assigned gender role and idealized representation, is the fruit of the country’s Confucian heritage as well as external influences from the West and Japan. Korean women have not yet reached emancipation as shown by the fact that they still do not own they own body and image and that they are subjected to the paternalistic ideal of beauty. Women’s higher education level is met by tough sexism in the workplace, and although they have more freedom and spending power they still suffer from the constant pressure to conform to beauty standards and expected behavioral traits. The strong backlash against those who do not conform also serves as a way to keep women in check and limit their emancipation.

However, all is not negative. With the new generation coming of age, more and more women are fighting against the system to gain recognition and equal rights in the workforce and it ripples to the private sphere through their increased independence. Korean gender roles are still changing and women will find a way to reconcile their need belonging to the group and their want for self-determination.

References

Choi, Hyaeweol. 2009. “”Wise Mother, Good Wife”: A Transcultural Discursive Construct in Modern Korea.” Journal of Korean Studies, Vol.14(1) , pp.1-33.

Chung, Yeon Shim. 2012. “The Modern Girl (Modeon Geol) as a Contested Symbol in Colonial Korea.” In Visualizing Beauty: Gender and Ideology in Modern East Asia, by Aida Yuen Wong. Hong Kong University Press.

Elfving-Hwang, Joanna. 2013. “Cosmetic Surgery and Embodying the Moral Self in South Korean Popular Makeover Culture.” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 11, Issue 24, No. 2.

Kim, Taeyon. 2003. “Neo-Confucian Body Techniques: Women’s Bodies in Korea’s Consumer Society.” Body & Society 9(3): 97–113.

Korean Overseas Information Service. n.d. “Women’s Role in Contemporary Korea.”

Lee, Annie Narae. 2014. “The Fight for Equality: Women’s Struggle to Defy Prejudice, Stereotypes and Tradition.” Groove, Issue 91, pp.58-65.

McKay, Anita. 2014. “The Working Woman: Is Korea Ready for Women in the Workplace?” Groove, Issue 91.

Ou-Byung Chae, Jung-Hae Choi. 2008. “Korean Society in Change: Statistics and Sources (I, II, III, IV).” Korean Journal of Sociology 42.

Park, Hyejin. 2014. “Qualified, trained and nowhere to go.” Groove, Issue n.91.

Raitt, Remy. 2014. “The Big Bucks in Beauty: From cosmetics to eyelid surgery, vanity spurs Korea’s economy.” Groove, Issue n. 91.

Ruth Holliday, Joanna Elfving-hwang,. 2012. “Gender, Globalization and Aesthetic Surgery in South Korea.” Body & Society, Vol.18(2), pp.58-81.

Turnbull, James. 2012. “Bikinis, Breasts, and Backlash: Revealing the Korean Body Politic in 2012.” The Grand Narrative, Korean Feminism, Sexuality, and Popular Culture.

—. 2013. “Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 3: Historical precedents for Korea’s modern beauty myth.” The Grand Narrative, Korean Feminism, Sexuality, and Popular Culture.

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes. Photo (cropped) by Jim Flores on Unsplash.

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes. Photo (cropped) by Jim Flores on Unsplash. Photo by Valentin Fernandez on Unsplash.

Photo by Valentin Fernandez on Unsplash. Which is why the following passage from Involuntary Consent: The Illusion of Choice in Japan’s Adult Video Industry (2023) by Akiko Takeyama, a professor of women, gender & sexuality studies at the University of Kansas, resonated so strongly. So strongly in fact, I didn’t even notice she also says “especially women” until I posted it here:

Which is why the following passage from Involuntary Consent: The Illusion of Choice in Japan’s Adult Video Industry (2023) by Akiko Takeyama, a professor of women, gender & sexuality studies at the University of Kansas, resonated so strongly. So strongly in fact, I didn’t even notice she also says “especially women” until I posted it here: