“There’s a word in Korean—inyeon (인연). It means providence, or fate.” Well so what?

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes. Image source: Naver.

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes. Image source: Naver.

To be clear, I haven’t actually seen Past Lives yet. In most of the world, everyone was able to watch it last summer; in Korea, it’s only finally coming out this March. But that opening line in the trailer is a huge red flag:

I realize I’m completely projecting, my title necessarily provocative. It’s just one line, devoid of context. I don’t know if its Orientalist undertone is the exception, or if it suffuses the whole film. But ugh.

Because why say something like that at all, if not to then stress some fundamental difference between the English and Korean concepts? It already feels like right up there with gatekeeping, essentializing discussions of how han, or jeong, or nunchi are timeless, immutable, untranslatable qualities that define all Koreans, which Westerners just could never fully understand:

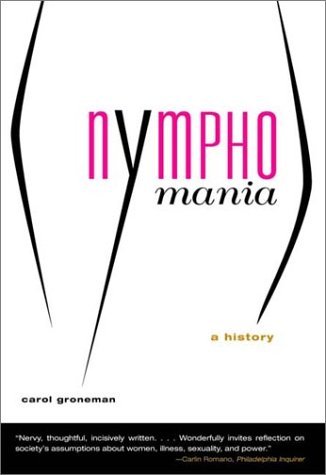

Source left: Absolutely not going to give this book any traffic. Source right: @RachelMinhee.

Source left: Absolutely not going to give this book any traffic. Source right: @RachelMinhee.

Source: Stolen from a Korean Facebook friend.

Source: Stolen from a Korean Facebook friend.

And definitely make sure to read about how the concept of “saving face” is a complete Western invention, and Minsoo Kang’s “The problem with ‘han’ 한 恨” article at Aeon:

Some people insist that han is a uniquely Korean idea that only Koreans can truly grasp. Yet it is about as useful at explaining everything Korean as the term ‘rugged individualism’ is at explaining everything American or the ‘Samurai’ is in capturing all that is Japanese. It is true that all the calamities and traumas of the modern era have provided Koreans with a great well of powerful emotional experiences from which to draw. But intense emotionality is hardly unique to Korean narratives, and the notion of a specific kind of sorrow/regret/frustration/rage that only Koreans can feel is absurd.

Despite the film’s almost universal acclaim then, and smart overseas friends’ glowing reviews, I was already feeling ambivalent about eventually watching it. I have to admit I’m just a natural contrarian too, especially when it comes to Korean and Korea-related films. Not at all because I think I know better than everyone somehow, but because it seems the more people that sing their praises, the more likely those films are to tick various boxes that turn me off. And, once I do voice any negativity, that my friends will become completely insufferable too, writing me off as a plebeian rather than admit their latest bestest film ever might be anything less than perfect.

Elaine knows exactly what I mean:

So, not going to lie, I felt vindicated over the winter as more and more Asian-American friends in particular also expressed their misgivings about the film. Then, finally, one linked to maverick Ian Wang‘s provocatively-titled “The Critics Are Wrong About ‘Past Lives” at ArtReview, its introduction alone confirming all my suspicions:

You’re watching a contemporary drama about East Asians who’ve immigrated to the West. The narrative can vary, but often depicts a conflict between an older first generation (stern, repressed) and a younger second generation (independent, rebellious). Its characters are honourable and decent. Despite their disagreements, you get the sense that the film doesn’t want you to think any of them have done anything wrong. In fact, they can feel less like real people and more like proxies for certain ‘types’: the tiger mother, the Westernised child. Peppered throughout are glib ethnic signifiers: lingering shots of kimchi-jjigae or jiaozi, a hackneyed reference to not wearing shoes in the house. You can feel the director ticking off boxes as they go, soliciting high relatability with low effort. It is a polite, earnest film, one that will surely receive awards attention. And yet you can’t help but walk away feeling dissatisfied – this was sold to you as a complex, nuanced story about immigration, so why does its view of immigrant life feel so shallow?

I’m tempted to say I rest my case. But on the contrary—unlike most of my film snob, probably soon to be ex-friends, I’m not going to dismiss anyone’s continued love for this film as some irredeemable intellectual failing on their part. So, whether you want to send me a rant or a rave, thanks in advance to those of you who have seen the film and who do take the time to share their thoughts on Yang’s critique. For who knows? I’m already inclined to see the film anyway, just to make up my own mind about it—and being able to debate you afterwards may be all the final persuasion I need!

Related Posts:

- Movie Review: Our Body/아워 바디 (2019)

- “Sex, Sass, and Sensibility in South Korea” 뭐야?

- “Return to Seoul” (리턴 투 서울, Retour à Séoul) Now Playing in Korean Cinemas

- Unpopular Opinion: “Kim Jiyoung: Born 1982” Didn’t Hit Hard Enough

- If You Understand Korean, Please Don’t Miss Out: “After Me Too” (애프터 미투, 2021) is Screening October 6-9!

- I’m Ready to Pay for Korean Feminist Films!

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)