Estimated reading time: 4 minutes. Image sources: Aladin, NamuWiki.

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes. Image sources: Aladin, NamuWiki.

“I want to tell you a story about my body and my sexuality. But it’s going to be so revealing and embarrassing for me, that I can say it only once. So please listen carefully.”

If you can please indulge me, I just want to say I’m very proud of myself for ordering Bodies and Women ‘몸과 여자들’ by Lee Seo-su. It will be the first novel I’ll have read entirely in Korean!

I was instantly sold on it by reviews that mention its intimate coverage of beauty ideals, gender socialization and body-shaming in schools, sexual assault, pregnancy, sex in marriage, pervasive sexual objectification, and the male gaze.

However, there’s also the matter of the other members in The Grand Narrative Book Club,* who are much more knowledgeable and well-read than myself, and have often already read the original Korean versions of the translated novels we discuss. Because while I count myself lucky that I’m never the most interesting person in the (Zoom) room, does the fact I’m the dumbest really need to be so obvious?

In 2023 then, I want to work on disguising that. Starting by getting into the habit of reading novels in their original Korean myself.

Unfortunately, Bodies and Women will not be turning up in the club anytime soon. Lee Seo-su seems to be a relatively new writer, with a discussion in Korean Literature Now about of one of her short stories being all I could find out about her in English. So, although I could translate those persuasive reviews for you here, really any translation add-on for your favorite browser should more than suffice. Instead, hopefully I will find many interesting things in the book itself to pass on later.

Sorry. I did say this post was an indulgence!

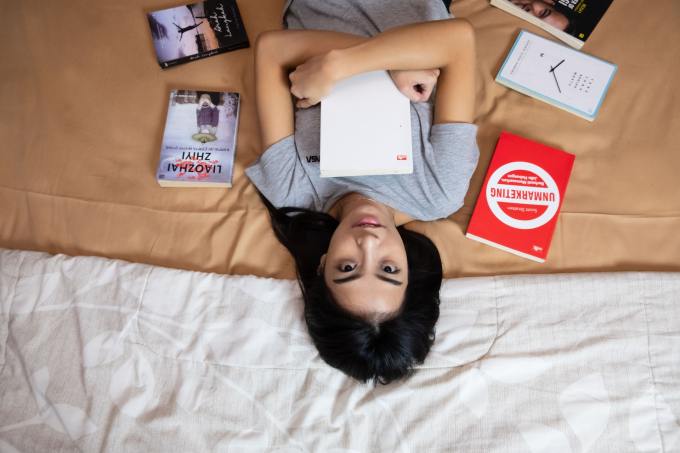

However, with that my writer’s block does seem to be cured now too, so it served its purpose. Let me offer some humor too, as a parting gift—but also, a reminder of precisely why those reviews were so persuasive, and books like it so necessary. For I shit you not: these two sponsored ads on Facebook, I saw back to back after googling “몸과 여자들” the hour previously:

Again frankly, probably the juxtaposition is a complete coincidence. After the book itself, googling “몸과 여자들” in fact mostly brings up images of women perusing fine male specimens. But more to the point, during the evening rush hour, Korean advertisers on Facebook deliberately target men with ads for lingerie etc., which they won’t buy, but which do persuade them to swipe left to be rewarded with more lingerie models, then with ads for oh-so-masculine power tools and gaming equipment which they might.

Also, ever since I hit my mid-40s I’ve been inundated with ads for libido and erectile dysfunction treatments, and doubt it’s just me. I don’t mean to laugh at anyone or their partners who actually need to avail themselves of such products, especially since I’ll probably be joining their ranks sooner rather than later (sigh). But many prove just as creepy as campy. For instance, this one where the model’s head was cut off, in stark contrast to when a different advertiser used the same stock photos of her to advertise diet products to women:

Also, ever since I hit my mid-40s I’ve been inundated with ads for libido and erectile dysfunction treatments, and doubt it’s just me. I don’t mean to laugh at anyone or their partners who actually need to avail themselves of such products, especially since I’ll probably be joining their ranks sooner rather than later (sigh). But many prove just as creepy as campy. For instance, this one where the model’s head was cut off, in stark contrast to when a different advertiser used the same stock photos of her to advertise diet products to women:

Then there’s these screenshots from yet another ad in my feed today, from which I’ll let you form your own conclusion to this post to!

*Finally, the book for January’s meeting on Wednesday the 18th is Cursed Bunny by Bora Chung (2017), translated by Anton Hur (2021); I’ll put up an official notice soon. Sorry for not doing so earlier, which is my fault for not realizing that I may not be the only person out there who hasn’t actually read it yet!

*Finally, the book for January’s meeting on Wednesday the 18th is Cursed Bunny by Bora Chung (2017), translated by Anton Hur (2021); I’ll put up an official notice soon. Sorry for not doing so earlier, which is my fault for not realizing that I may not be the only person out there who hasn’t actually read it yet!

Related Posts:

- Two Ads With the Same Female Model, for the Same Kind of Product. Spot the Differences in the One Aimed at Men.

- Why Does Korea Have so Many of Those Damn Smutty Ads?

- Headless Images Dehumanize Obese People. It’s Now a Fact.

- There are More Entry-level Korean Women Journalists than Men These Days. So Why do Most Leave the Industry in Less Than 10 Years?

- Making Sense of the NewJeans “Cookie” Controversy

- Blackpink’s Rosé Deserved So Much Better Than the “Young Silly Woman Puts Product on Head” Advertising Trope.

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)