(Source: Busan Metro, 2 September 2009)

(Source: Busan Metro, 2 September 2009)

An image that simply begs commentary. But what is noteworthy about it exactly?

One thing is the tendency to use women’s bodies to showcase vehicles, well satirized here by replacing women with men in a similar photoshoot. But that is hardly unique to Korea, nor particularly strong here, whereas my general purpose with this series is to highlight interesting features of Korean society. So it’s the use of Caucasian women that I want to discuss here, as they’re so common in Korean advertising that sometimes there’s even more of them than Korean ones.

Before I began writing though, I had a thought: can’t Korean advertisers ever use non-Korean models without overanalysis, and — yes — perhaps implicit criticism from myself for doing so? No, of course they can. And, serendipitously, earlier this week Lisa at Sociological Images provided a fuller response to that charge, indeed an overall rationale that will inform this series in the future also. Here it is, but adapted to this blog:

I often present a single example of a cultural pattern. If you’re a member or observer of the relevant culture, that single example might ring true. That is, you might recognize it as one manifestation of something you see “out there” all the time.

I often present a single example of a cultural pattern. If you’re a member or observer of the relevant culture, that single example might ring true. That is, you might recognize it as one manifestation of something you see “out there” all the time.

But it’s still just one example and it’s not very convincing to someone who is skeptical that the cultural pattern exists, especially if it’s subtle.

But one advantage of being a niche blogger is that posts on one’s subject(s) are cumulative. I can even put up single manifestations of a cultural pattern and, even if it’s not very convincing at the time, the other evidence on the blog (and the evidence yet to come) may sway even some skeptics.

It is in that spirit that I offer the opening advertisement.

The choice of the models ethnicity may be random, but I am going to suggest that it is not…

And yet there are so many examples of Caucasians in Korean advertisements on this blog to provide, and so many factors involved in the choices of them, that to simply provide dozens of links at this point would be to confuse rather than enlighten readers. Therefore, my purpose with this post is to provide a single definitive guide to the subject that people can refer back to in future, not least myself!

To begin then, consider the empirical evidence for the disproportionate numbers of Caucasian women in Korean advertisements. Surprisingly given their seeming ubiquity though (something I’ll return to), there have actually been very few English-language studies of East Asian advertisements that have incorporated race as a main factor of their inquiries, and I am aware of only three that have done so of Korean ones. Here they are in chronological order of publication, with very brief summaries of their findings and links to the posts where I discuss them in more detail:

• Hovland, R. et.al. “Gender Role Portrayals in American and Korean Advertisements”, (Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, December 2005; open access copy no longer available).

Using various 2000 editions of selected Korean and American women’s magazines, Hovland et. al. found that 30% of Korean advertisements in them featured Caucasian female models, whereas only 1.9% of US advertisements showed Asian female models. Of particular note here, both Korean and US magazines for middle-aged women showed more Korean and Caucasian models than their counterparts for younger women respectively; see here for the details.

• Kim, Minjeong & Lennon, Sharron “Content Analysis of Diet Advertisements: A Cross-National Comparison of Korean and U.S. Women’s Magazines” (Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, October 2006; open access copy no longer available).

As discussed in the second half of this post, the advertisements in the various 2001 editions of selected Korean women’s magazines examined actually had more Caucasian women than Koreans: 52.3% vs. 47.7% respectively, compared to 84.9% Caucasian women in advertisements in U.S. magazines.

• Nam Kyoungtae, Lee, Guiohk & Hwang, Jang-Sun “Gender Role Stereotypes Depicted by Western and Korean Advertising Models in Korean Adolescent Girls’ Magazines“, Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, TBA, San Francisco, CA, May 23, 2007; downloadable here.

Of the total of 644 female models found in selected advertisements (one page or bigger and showing full adults) from selected Korean women’s magazines from 2002 and 2003, 57% were Korean and 43% were Western. Of 299 male models counted, 59.2% were Korean and 40.8% Western. And of particular interest, as I wrote here:

…Western women were more likely to be depicted in revealing clothes and or nude than Korean women, but at the same time they were also likely to be portrayed as independent, self-assured, and assertive than them too, and by no means just in a sexual sense. Again, this finding is true of Western and Korean men too…

To be fair, this at least in part echoes the the hypersexual state of Western advertising today. And rather than supporting the artificial dichotomy between chaste Koreans and oversexualized Caucasian (or Westerners) that at the heart of this post, the internal dynamics of the Korean magazine industry reveal that Korean women are active and willing consumers of the cultural and sexual norms that such advertisements literally embody, the incorporation of which into patriarchal Korea is not without friction. Not to imply that all positive changes in Korea are Western-derived of course, but regardless there are certainly a lot of advertisements with Caucasians out there.

( Source: Naver )

( Source: Naver )

Or are there? I’d wager that many heads would have been nodding with that last statement, and, granted, some Korean clothing labels for instance – Beanpole and Hazzys come instantly to mind – do seem to use exclusively Caucasian models. But then appearances by Caucasians in Korean-made television commercials like the above, for instance, are actually the exception rather than the rule. And with the proviso that White privilege is very much alive in Korea (the existence of which I take for granted that readers agree on), and, without implying that Koreans want to look White, that this still has a strong influence on both Koreans’ preferred cosmetic surgery operations and their huge numbers, in hindsight I’d be hard pressed to think of any segment of the Korean advertising industry that used Caucasian models to the extent researchers found in women’s magazines.

Unless of course, a great many of them were for lingerie that is.

As long-term readers will well know, it turns out that the reason for this is because before the restrictions against the use of foreign models in advertising was lifted in 1994, lingerie modeling in Korea was often done by pornographic actors (update: to be more precise, nude models) This gave it a negative image among Korean female models, the enduring strength of which was revealed recently by these ones who did model lingerie but nevertheless felt compelled to literally disguise themselves while doing so, and all quite ironic considering how willing many are willing to objectify their breasts otherwise (see here, the video here, and here for some notorious examples). Case closed then?

Not quite. Consider what I wrote a few months ago on the subject:

Not quite. Consider what I wrote a few months ago on the subject:

…lingerie advertisements are ubiquitous in Korea, and it’s a rare commute when I don’t have the slightly surreal experience of seeing ones featuring scantily clad Caucasians in one subway car, then seeing others with fully-clothed Koreans like [these] in another when I transfer (sometimes, you can even see both in the same car). Seriously, it’s no exaggeration to say that Koreans’ convoluted and often contradictory notions of sexuality and race literally stare me in the face everyday, and in a form that means that I’m particularly likely to sit up and take notice.

Yes, that is indeed a lingerie advertisement on the right (source). And regardless of the actual reasons for a phenomenon, once we think we’ve found the reasons for it, those shape the filter through which we take in new data. Personally then, I originally thought the use of Caucasian lingerie models demonstrated that Korean women had Caucasian body ideals, which prompted me to write this post on the subject last April. Once the stigma attached to lingerie modeling came to light that June though, then that link I had made was no longer sustainable…but not the Caucasian body ideals themselves, which there’s still a wealth of other evidence for (and see this post again). In that vein, while 4 years ago Michael Hurt was also mistaken in his proffered reasons for the numbers of Caucasian women in lingerie advertisements, writing in his blog Scribblings of the Metropolitician…

One thing that I also notice is that in underwear and other commercials that require people to be scantily-clad, only white people seem to be plastered up on walls in the near-buff. Now, it may be the sense that Korean folks – especially women – would be considered too reserved and above that sort of thing (what I call the “cult of Confucian domesticity”). Maybe that’s linked to the stereotyped expectation that white people always be running around all nasty and hanging out already, as is their “way.” Another possibility has to do with the reaction I hear from Korean people when I mention this, which is that white people just “look better” with less clothes, since Koreans have “short leg” syndrome and gams that look like “radishes.” The men are more “manly” and just look more “natural” with their shirts off. Hmm. The thoughts of the culturally colonialized? Perhaps I’m being too harsh? My hunch is that it’s all of the above. Take a look.

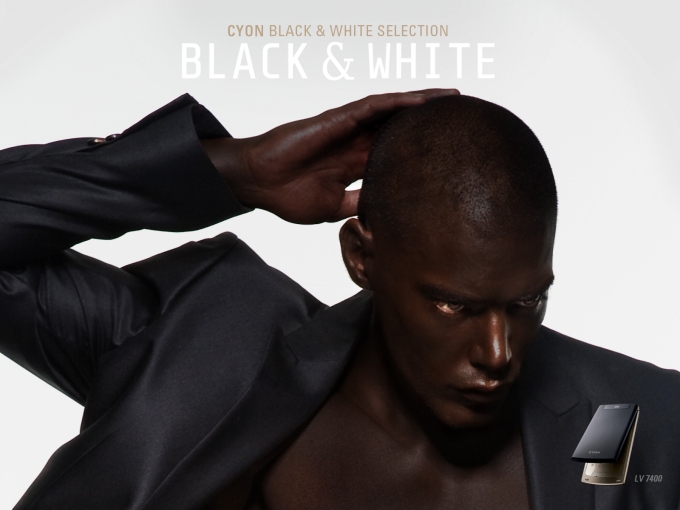

…not only did I heartily agree with his thoughts when I first read them, but I still agree with them, because they are not just based on the numbers of Caucasians in lingerie advertisements. In particular, of the following 2003 advertisement with Ahn Jung-hwan (안정환) he wrote:

A recent favorite, reflecting the relative position of Korean masculinity vis a vis whiteness, specifically white women. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the relatively greater financial power that has made Korean men an attractive partner – or at least potential plaything – of Eastern European and Russian women, and that many of them now enter the country under the E-6 “entertainment visa.” In any case, this is a fascinating statement on the changing status of “the white” in relation to Korean masculinity. No longer the inaccessible Playboy fantasy held by many men in a developing Korea that had been culturally (and partially symbolically sexually) dominated by the United States – now the tables are turned. The product being sold here is a cream to make/keep one’s skin “white.” Don’t even get me started.

And lest long-time observers of Korea feel that this particular advertisement has become somewhat iconic and overanalyzed by the Korean blogosphere, it is but one of many examples.

Before providing a context for those in the remainder of this post though, I should point out that I don’t think that lingerie advertisements by definition sexualize the models featured, and so I disagree with Michael Hurt’s seeing further evidence of the sexualization of Caucasian women in the ridiculous setting of this advertisement for instance, as regardless of the source of the advertisement and/or the ethnicity of the models, worldwide they can similarly have “folks sitting around in their skivvies [that] could just as well be on the veranda of a bistro in the south of France. Eating strawberries in a bathtub in lingerie, with a towel wrapped around one’s head.” Indeed, rare Korean lingerie advertisements with Korean models are no different, and when it comes to sexualizing lingerie – nay, almost any item of woman’s clothing – it often pays to be subtle. Consider this one with Shin Min-a (신민아) that came out this summer for instance: while it is significant because previously one never saw Korean celebrities wearing the lingerie at all when they endorsed it, and is probably a belated reaction to the fact that discreetly showing one’s lingerie off has actually been the fashion for years now, personally I see much more significance in the fact that it seems designed for a male gaze.

As you might vaguely recall, the advertisement that prompted this post wasn’t actually a lingerie advertisement. But having Caucasians in the vast majority of those – for whatever reasons – does at least feed into the false dichotomy of chaste Koreans and overly-sexualized Caucasians. And although it’s by no means the most blatant example of its kind, the choice of outfits in it still makes it very much Exhibit A in the argument for the existence of those stereotypes (as an aside, see this post for the issues raised when skimpy clothing is donned for a good cause, like women in bikinis washing only hybrid cars). Let’s now consider the other evidence.

First, there were the recent plans to set up a nudist beach on Jeju island specifically in order to attract foreign tourists, especially Caucasians/Westerners. Apparently, this was because many were already regularly stripping off on Jeju beaches despite local sensibilities, but in the absence of anything to support those claims, and considering that Korean reporters regularly simply make stuff up and/or impose their own opinions on a report while attributing them to others (see here and #1 here respectively for recent examples), then when I heard of the idea I was much more inclined to believe that Jeju government officials came up with it completely independently. And why? Probably based on the conflation of nudity at beaches with sex said Brian in Jeollanam-do, “implying that the point of the former is to stimulate one’s appetite for the latter,” and which in turn points to “a pretty base assessment of the tastes of foreigners and foreign tourists.”

To be fair, in many senses exaggerated notions of foreigners sexuality are merely a method by which particularly older Koreans deal with and account for the uncomfortable reality of Koreans’ own sexuality, and so as Michael Hurt points out here, public displays of affection by young Koreans are often rationalized by certain Koreans by claiming that the couples involved are Japanese. No, really. But for a more tangible “other,” you need the Occident of course, which is why Korean public opinion holds Western celebrities to such different standards to Korean ones.

( Source: Naver )

( Source: Naver )

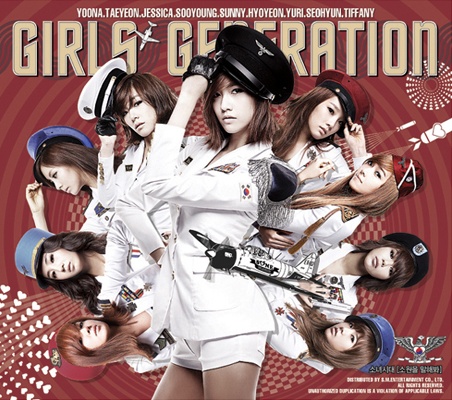

So while it is okay for Korean women to dress up as Paris Hilton in order to promote the Korean airing of her reality show for instance, and she regularly appears on Korean television, endorses Korean products, and literally her every word about Korea is literally lapped up (no matter how inane), on the other hand Korean female’s celebrities careers have been ruined simply for having sex with their boyfriends, or even merely being accused of making a Hiltonesque sex tape. True, Korea’s well-known cultural cringe is very much involved when the attention of Western celebrities – any celebrity – is sought, but the same principles still apply for both less notorious Western stars and Korean celebrities’ less extreme deviations from sexual norms. Hence like Paris Hilton, Lady Gaga above was recently fawned over on her recent visit to Seoul, and yet seemingly every other week: Korean groups are banned from the airwaves for even the most innocuous of lyrics (see #2 here, and the more recent case here); female groups struggle to present female sexuality as something other than dressing and acting like schoolgirls; and international models are criticized for appearing nude in photoshoots (yes, I can admit my mistakes). And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

But you get the idea. Next then, there is confirmation from the grass roots: Brian provides ample evidence that foreign women in bikinis are heavily targeted by Korean newspaper photographers for instance, and I must also mention that a great many Caucasian female friends have mentioned being groped and otherwise sexually harassed by Korean men to me. Of course, that is merely anecdotal evidence, and not having my blogger’s hat on at the time (I do take it off occasionally), I didn’t think to ask how that compared to experiences in their home countries. Now that I am in that frame of mind though, I’d be grateful if readers could fill me in with their own experiences, and by all means if you haven’t ever faced either problem too, as responders can be somewhat self-selecting sometimes.

But of course Korean women are also frequently photographed at beaches and/or and sexually harassed, and indeed because of that there was a short-lived experiment with women-only subway cars in Seoul a few years ago (but groping is on the rise again). Despite that, there are still good reasons to suppose that Caucasians might be targeted more: in addition to the stereotypes perpetuated by Western media itself of course, there is the ethnic make-up of prostitutes here.

In itself, the Korean prostitution industry is so big, so intimately tied to Korea’s economic development, and with such a pervasive impact on the current low position of women here, it really requires a separate blog devoted to it. Finding a short introduction to point readers towards was a bit of a challenge then, but surprisingly the Wikipedia article on the subject is a good start. Once you’ve read that, I recommend following it up with Matt’s plethora of articles on the subject at his blog Gusts of Popular Feeling by clicking here (if that doesn’t work, simply copy and paste “prostitution site:http://populargusts.blogspot.com/” into Google), and with apologies for not mentioning them myself, other bloggers by all means feel free to promote your own posts on the subject in the comments section. My concern here though, is specifically the fact that it is primarily Russian, presumably Caucasian, women that are trafficked to work in the industry, for which I offer the following links, in roughly chronological order (source right: Korea Discussion Forums):

In itself, the Korean prostitution industry is so big, so intimately tied to Korea’s economic development, and with such a pervasive impact on the current low position of women here, it really requires a separate blog devoted to it. Finding a short introduction to point readers towards was a bit of a challenge then, but surprisingly the Wikipedia article on the subject is a good start. Once you’ve read that, I recommend following it up with Matt’s plethora of articles on the subject at his blog Gusts of Popular Feeling by clicking here (if that doesn’t work, simply copy and paste “prostitution site:http://populargusts.blogspot.com/” into Google), and with apologies for not mentioning them myself, other bloggers by all means feel free to promote your own posts on the subject in the comments section. My concern here though, is specifically the fact that it is primarily Russian, presumably Caucasian, women that are trafficked to work in the industry, for which I offer the following links, in roughly chronological order (source right: Korea Discussion Forums):

• Humantrafficking.org, which has a basic introduction to the subject and links to archived articles.

• Human Trafficking & Modern-day Slavery, with a similar archive.

• Michael Hurt’s October 2006 post on the subject, with many links itself.

• A May 2007 article from the JoongAng Daily.

• Robert Koehler’s January 2008 post at The Marmot’s Hole on the fact that a US Congressional Research Service report on human trafficking labeled Korea a major destination for sex tourism.

• GI Korea’s post at ROK Drop a week later on Korea being taken off that list.

• An editorial in The Hankyoreh in February of this year on the fact that it is the victims of human trafficking that are often persecuted for engaging in prostitution, despite being tricked and/or forced into it.

• Finally, a post by Robert Koehler in April on the busting of a brothel in Gangnam, which had several Russian prostitues.

Last but not least, no post on the title topic would be complete without the related subject of the Korean media’s portrayal of Western, Caucasian male teachers as sexual predators, for which I recommend this post by Matt and the links I provide at #1 in this post for getting a grip on. Apologies in advance to Matt in case I’ve covered any of the same material that he does, who also looks at the portrayal of Caucasian women as sex objects in that post.

In closing, again please feel free to link to and/or discuss any related subjects and posts that you think should be included here (my aim is to make the post as inclusive as possible), and I’d be especially grateful for readers passing on any of their own practical experiences with the issues raised in it. And apologies to everyone for the delays to writing this post and responding to comments and emails, as on Wednesday the wifi on my laptop completely stopped working…only to miraculously turn back on the instant the repair guy walked through my front door on Friday!

(For all posts in the “Korean Sociological Images” series, see here)

(Source)

(Source)![Copyright for the NEWSIS [Photo Sales:02-721-7414]](https://thegrandnarrative.files.wordpress.com/2011/12/lee-da-hae-soju.jpg?w=1100) Even though there does seem to be an increasing backlash against excessive photoshopping in recent years, at least in Western countries, the exposure this paper has received in the media has still been (pleasantly) surprising, with articles on it published in the likes of the New York Times, the Guardian, Nature, and Wired. I think the reason is that several European governments have already been looking for ways to quantify how much a particular image has been manipulated, to be put as some sort of numerical rating next to it wherever it is displayed, and this new software provides exactly that. Indeed, I wouldn’t be surprised if such disclosures become required by EU law within the next 5 years, especially now that this software is available.

Even though there does seem to be an increasing backlash against excessive photoshopping in recent years, at least in Western countries, the exposure this paper has received in the media has still been (pleasantly) surprising, with articles on it published in the likes of the New York Times, the Guardian, Nature, and Wired. I think the reason is that several European governments have already been looking for ways to quantify how much a particular image has been manipulated, to be put as some sort of numerical rating next to it wherever it is displayed, and this new software provides exactly that. Indeed, I wouldn’t be surprised if such disclosures become required by EU law within the next 5 years, especially now that this software is available. (Source)

(Source)1. that men initiate “skinship” (aka physical affection through touch) without asking

(The first interracial kiss on US television, November 1968)

(The first interracial kiss on US television, November 1968) (Source)

(Source)

(Source:

(Source:

argument that at the very least

argument that at the very least