Estimated reading time: 2 minutes.

Estimated reading time: 2 minutes.

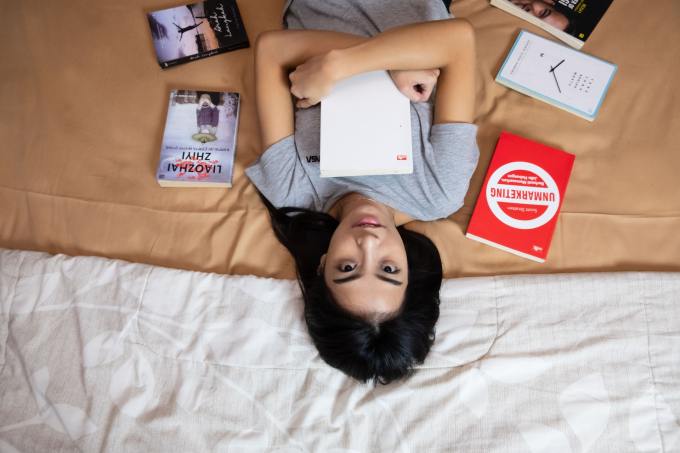

To round off our last book club meeting of the year, may I present I Want to Die But I Want to Eat Tteokpokki: A Memoir by Baek Se-hee, first published in 2018 and recently translated into English by Anton Hur. Described as “part memoir, part self-help book, and completely engrossing,” by The Korea Society, I Want to Die “is a book that captures the edgy relationship many millennials and Gen Z-ers have with hopelessness, hunger, and the pressure to be perfect.” It also provides, according to Willow Heath of Books and Bao, “a window into the mind of someone with depression, and a hand on the shoulder of anyone who suffers with it themselves,” and I just can’t wait to read it!

Please see LibraryThing, The StoryGraph, GoodReads and the videos below for reviews, and then, if I Want to Die still appeals, I’d like to invite you to our meeting on Wednesday 21 December, at 8:15pm Korean time. If you are interested in attending, please contact me via email, or leave a comment below (only I will be able to see your email address), and I will contact you to confirm, and will include you in the club reminder email with the Zoom link a few days before the event. At the same time, I will also post a SPOILER FILLED list of suggested discussion topics and questions below, which we’ll use to loosely structure the meeting (so please watch this space!).

But I want to emphasize that they will definitely only be suggestions, as I stress that the meetings are very small and informal really. And also, to help ensure that they remain as safe a space as possible, that there’s a limit of 12 participants including myself. So please get in touch early to ensure your place (and give you time to read the book!).

See you on Zoom!

♥♥♥

As Willow says, this is a very experimental book, both in subject and in format, so mostly these suggested discussion topics and questions will very much just be my observations:

My first is how valuable it is that a book about depression and therapy has become a bestseller in Korea. Mental problems are still hugely stigmatized here, not helped in recent years by incidents such as a murder/arson case by a schizophrenia patient in Jinju in 2019, as well as numerous attacks by men on women that are invariably attributed to mental illness rather than also acknowledging the role of misogyny, which is a much more politically sensitive subject. Accordingly, the government’s mental health care budget and number of trained personnel fall well below OECD average.

In such circumstances, it is very admirable and brave that Baek Sehee has deliberately set out to explain what depression is like for the public. That despite how vulnerable this makes her, she has shown the non-scary and non-judgemental reality of what therapy is actually like (sort of; I’ll return to this below), which is a good start towards encouraging more people in need to visit therapists. I’ve also heard that, especially in Korea it’s very valuable hearing the experiences of an ordinary person rather than a celebrity, and likewise the strong emphasis on her problems with her body image would find a lot of resonance with Korean readers—and Korean women in particular.

Related, can anyone speak to the impact of BTS’s recommendation? Alas, I’m not a fan, so I’d be interested in hearing more about the circumstances of that. Thanks!

♥♥♥

Next, in raising the subject of therapy we can certainly talk about the different attitudes, perceptions, and experiences of it between Koreans and people from other countries, and perhaps also between US residents and people from other English-speaking countries. Indeed, one Western expert(?) is actually quite scathing in her criticisms of the therapist, and I personally thought the therapist tended to be too quick to label what Sehee was going through, regularly shoehorning her issues into various convenient narratives and/or mental conditions rather than acknowledging her individuality and their complexity.

Speaking to the point earlier about how real a picture of therapy sessions Sehee provides, we can also discuss the issue of the transcripts of the conversations being very packaged and edited to make their points. (There’s no interjections, there’s no pauses, there’s no crying or missing minutes, and so on.) In doing so, I don’t think Sehee was being dishonest per se, as it may just have been a practical necessity for the sake of readability. But you could argue that in giving unrealistic expectations of sessions it slightly undermines her intentions to encourage and guide others to seek therapy.

Also, what sex do you think the therapist was? Why?

♥♥♥

How did you find the structure?

In my reading of reviews, the vast majority of people liked the transcripts, but by the middle began to find them increasingly muddled and repetitive, with no clear theme or narrative. The essays—”random observations”—at the end were also almost universally disliked, some reviewers accusing of them of being just padding to justify the book format. I tend to agree.

♥♥♥

Finally, what were the positives and the negatives of the book for you?

Many, we’ve already covered. Additional potential positives include the author’s honesty, and her therapist’s ability to demonstrate links between her feelings and her negative behaviors and habits of which she had previously been unaware—and which is one of the first steps towards addressing them. Reviewers also mention time and time again just how relatable she is.

I’m going to be a contrarian though, and argue that relatability is mostly because there are just so many experiences and feelings covered. That of course there’s going to be some moments when you can completely identify with Sehee and what she’s going through, because who hasn’t ever been depressed, had issues with coworkers, or felt fat (etc.) at some point?

That said, if you deeply related to any—even many—such moments, if they moved you, if Sehee’s thoughts and feelings and/or the therapist’s advice were truly beneficial to you, then nobody can or should want to deny you any of that.

It’s just…there were no moments like that for me.

Probably, because although a lot of people found that although the book can appear to be a very general one about depression and therapy, really her core problems are very specific to her. The advice given, not really relevant to anyone without the exact same.

Indeed, despite the title, do suicide and tteokbokki get any mention at all? Is the book really as universal and relevant as it’s often described and marketed?

My verdict then: 2 out of 5. How about you?

Sehee does have my great admiration and respect for helping start the long, difficult, but very urgent and necessary conversation about mental health that needs to take place in Korea. Having read I Want to Eat Tteokbokki, now I very much hope to read its sequel, and from other authors it spawns on this topic, a genre which was previously dominated by psychiatrists themselves. But however valuable it was to open the doors for more such possibilities, unfortunately this particular one fell flat for me, the delivery and structure somewhat flawed. Sorry!

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)