Kim Yuna may well be the “Ad Queen” in South Korea, but the reality is that precious few female athletes have the face and body-type necessary to get noticed by Korean advertisers. Whereas for male athletes, they just have to be good at their sports.

Estimated reading time: 12 minutes. Image source: YouTube via Humoruniv.

Estimated reading time: 12 minutes. Image source: YouTube via Humoruniv.

My writing is pretty erratic these days, because reasons. Sorry about that. One of those reasons is worth mentioning though: I’ve been fielding lots of inquiries from journalists instead. Here are some of the results:

First up, from “In Pyeongchang, a surprise visit from Queen Yuna” by Nathan VanderKlippe in The Globe and Mail:

For “Korean advertisers, all their Christmases came at once when Kim Yuna became popular,” said James Turnbull, a South Korea-based author who writes about Korean feminism, sexuality and pop-culture.

By at least one measure, celebrity matters more in South Korea than elsewhere. Roughly 60 per cent of the country’s advertisements feature endorsements, some six times higher as those in the United States. Former South Korean advertising executive Bruce Haines once called the country’s advertising “beautiful people holding a bottle.”

Mr. Turnbull is critical of the unfair standards this imposes. South Korean Ahn Sun-ju was among the best golfers in the world, but South Korean advertisers said she needed plastic surgery if she wanted to appear in commercials.

Ms. Kim, however, “was tailor-made for Korean advertisements,” Mr. Turnbull said. She is “young, attractive, photogenic, a figure skater – thin, tall – whose body is the type they want.”

“The question isn’t so much why she retired so early as why she retired so late,” he added. “Because really, did she enjoy what she was doing?”

There’s lots to unpack in that short segment. Starting with giving credit to Roboseyo for the point about advertisers’ love of Kim Yu-na, who wrote that in 2009:

Kim Yu-na…is a teen-aged figure skating phenomenon out of Seoul. She’s only eighteen years old now, and she’s been kicking the crap out of the ladies’ singles category for a few years already. She’s telegenic and cute: she appears in TV commercials here in Korea and sells, better than most of Korea’s other “Best in the world/Korea at X” stars, for example Park Ji-sung (family name Park), the Soccer (that’s Football to the rest of the world) star who is holding his own impressively on Manchester United, but who’s so ugly, and un-charismatic in front of the camera, that they can only make commercials like this [long since deleted example—sorry]: keep the camera at a distance, and show him kicking stuff, because that’s the only time he looks impressive. (Notice at the end of the ad, when the close-up is as short as they can make it and still have him be recognizable, as if the camera’s afraid to get close to his face).

Catch me on a bad hair day, and I’m hardly charismatic in front of a camera myself. I’m all about widening the media’s narrow range of beauty ideals too. But it’s objectively true: even at his physical peak, Park Ji-sung’s face would never have launched a thousand ships. As a male celebrity however, his phenomenal popularity for his sporting prowess meant that advertisers still flocked to him nonetheless, especially after it became apparent he was responsible for one million new Manchester United-branded Shinhan Mastercard accounts. Add various other factors responsible for that world-high celebrity endorsement rate of 60 percent of TV commercials (see my journal article), plus—in this case—Koreans’ (in)famous toleration of blatant photoshopping, then you can hardly blame Gillette for joining his bandwagon in 2009:

Sources: Hidomin (2006), Betanews (2009).

Sources: Hidomin (2006), Betanews (2009).

Like Park Ji-sung, golfer Ahn Sun-ju was one of the best at her sport in Korea. Unlike Park Ji-sung, she was cursed with being a woman, which meant advertisers were very concerned about her appearance—and her body type didn’t fit their narrow requirements. Frustrated with her ensuing lack of corporate sponsorship, she ultimately chose to compete in Japan instead, where—to my shock and pleasant surprise—advertisers were more interested in her sporting achievements. As The Korea Times explains:

…[Ahn] said that when she competed in Korea, her ability as a golfer was never enough.

“Some (potential Korean) sponsors even demanded I get a plastic surgery,” she said. “Companies did not consider me as a golf athlete, only that I was a woman. It mattered most to them was whether my appearance was marketable. I was deeply hurt by that.”

Ahn her made pro debut with the KLPGA in 2006 and won six tournaments before jumping to the JPLGA. But despite her stellar play, she struggled to find a corporate sponsor in Korea.

“As you can see, I do not have a pretty face, I am not thin, I am not what you would call sexy,” Ahn said. “But does that mean I shouldn’t be playing golf?

“Japanese companies, on the other hand, focused on my ability as a golfer. They are more concerned about my performance and how I treat my fans. I am being sponsored by six Japanese companies, including a clothing brand.”

Writing in Kore in response to that article, Ethel Navales speculates that we can’t “say for certain that Ahn’s decision to move to JLPGA was due to Korea’s inability to accept her physical appearance”, and that she may have just been reacting to one negative experience, so “we certainly shouldn’t assume that the KLPGA puts those expectations on [all] their players.” But personally, I see no reason to challenge Ahn’s stated motivations for leaving. As for the KLGPA, I turned to Transnational Sport: Gender, Media, and Global Korea (2012) by Rachel Miyung Joo to learn more about its attitudes towards its female players, but unfortunately she doesn’t mention Ahn at all, focusing largely on Korean women in the (US)LGPA instead. So, while her descriptions of their Orientalist and sexualized depictions therein are fascinating, and her description of its 2002-2007 “Five Points of Celebrity” marketing drive (a.k.a. “Anti-butch Campaign”), “understood to place a large emphasis and personalities of the players rather than on their performance as athletes” (p. 153), sounds particularly relevant here, indeed we still can’t automatically assume the same of the KLPGA. But she does note that “[i]n the current media climate in South Korea, female golfers are often sexualized through sports tabloids, fansites, and advertisements” (p. 156; see Le Coq Sportif example below). Also, her description of what happened to the Korean image of predecessor Pak Se-ri, “probably the most popular athlete in South Korea at the end of the twentieth century”, is quite telling. Because after Pak left for the LGPA in 1998:

Sources: Kaikaihanno (Pak Se-ri, 1998), Yonhap (Ahn Sun-ju, 2014)

Sources: Kaikaihanno (Pak Se-ri, 1998), Yonhap (Ahn Sun-ju, 2014)

…there [was] a considerable shift in ideas of public sexuality in [South Korea]. This shift can be read in the changes to the public appearance of Pak Se-ri. She was transformed from a dowdy twenty-something golfer at her debut to the tidy player of today through a national makeover. The masculinity of Pak—her broad shoulders, strong legs, dark tan, baggy shorts, and flat short hair covered with ill-fitting baseball caps—did not detract from her initial national fame….[But] [o]ver the years, her public image has been transformed through a wardrobe redo and the use of heavy makeup. She is often featured in women’s magazines in tailored designer sportswear with highly stylized hair and makeup. In the photos, she strikes poses that emphasize her “feminine side”—taking a stroll in the wood, relaxing on a couch, playing with her dogs, or cooking in her kitchen. The transformation of a tomboyish national icon to the womanly figure of today demonstrates that, although femininity was not a requisite for her national importance, she was normalized into public femininity through the transnational circuit of images of professional golf.

“In the current media climate in South Korea, female golfers are often sexualized through sports tabloids, fansites, and advertisements.” One of many long, lingering shots of conventionally-attractive, (now) JLPGA player Lee Bo-mee in a 2016 Le Coq Sportif commercial. Source: YouTube.

“In the current media climate in South Korea, female golfers are often sexualized through sports tabloids, fansites, and advertisements.” One of many long, lingering shots of conventionally-attractive, (now) JLPGA player Lee Bo-mee in a 2016 Le Coq Sportif commercial. Source: YouTube.

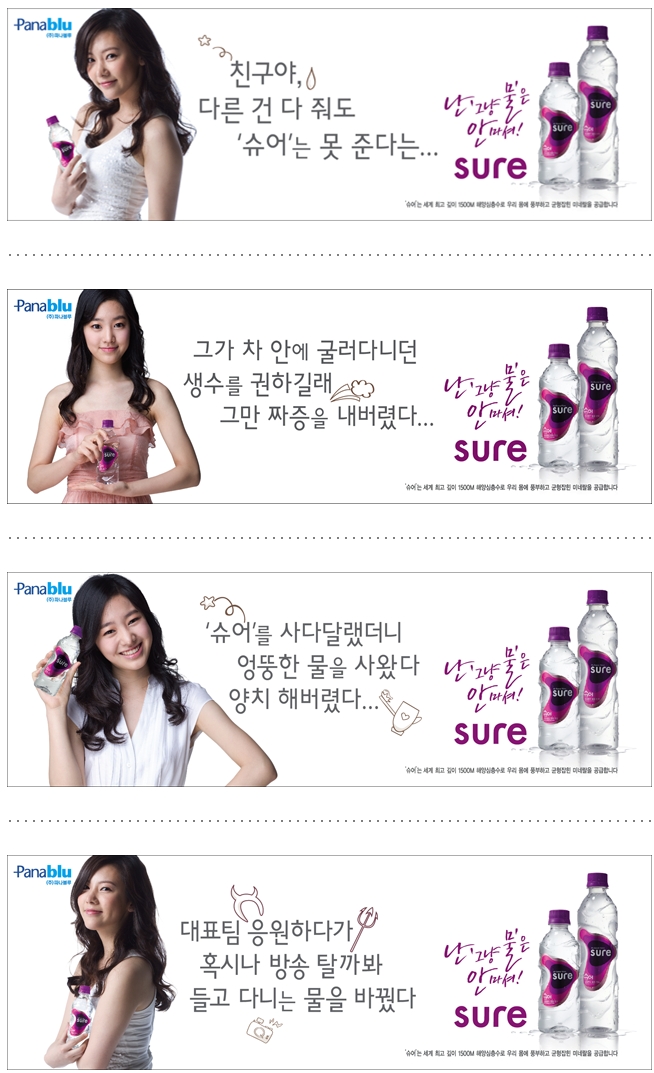

In contrast, Kim Yuna shares the body type and looks of K-pop girl-group members, who are specifically chosen for their ensuing, very narrowly-defined suitability for advertising. So it comes as no surprise that, like them, the vast majority of her numerous endorsements appear to be for beauty and dieting-related products.

To note that isn’t to diminish her considerable achievements and hard work. But it’s entirely possible she would never have become such a national icon if her body didn’t fit the part. As was the case with Yi So-yeon, Korea’s first astronaut, whose treatment by netizens and the media was really quite shocking in comparison.

Finally, just for the record, the point about her retirement was actually made by Nathan, but I agreed. Also, it’ll be interesting to see to what extent the Garlic Girls’ endorsements will challenge all these body-standards for female athletes. But it’s time to move onto the (much shorter) second article.

Update, July 2018: While preparing for my interview with Nathan, I remembered that a Korean journalist had made similar comments about a female golfer in 2016, and was consciously echoing him TBH, but I couldn’t find his article at the time. Now that I’ve just relocated it though, I was surprised to learn that he was actually talking about Park In-bee, who by coincidence very closely resembles Ahn. Unlike with Ahn however, one additional factor behind advertisers’ disinterest in her may be that her family moved to the US when she was 12 (she’s now 29), and that she only competed in Korea for the first time in May this year.

♥

Next, again for Nathan, a few days later I was quoted in “Behind Olympic death threats, a South Korean fan culture that takes speed skating seriously“,

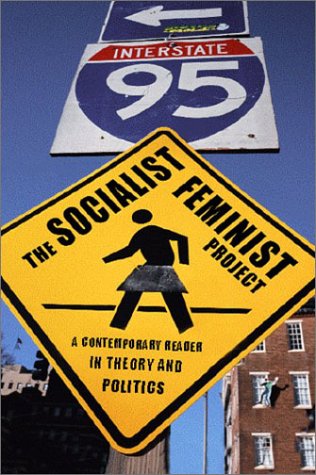

It doesn’t help that the South Korean sense of nationalism also “stresses Koreanness through having Korean ‘blood,'” said James Turnbull, a writer and speaker on Korean culture. “This means many Koreans react the way they do because they feel like a member of their ‘family’ has been cheated.”

Admittedly, that last possibly sounds a little patronizing coming from a foreign observer. So I would have preferred Nathan had noted that it was actually my Korean friend Ji-eun that said that, attempting to explain things after I expressed my mystification at the Korean (over)reaction to the Apolo Ohno controversy in the 2002 Winter Olympic Games—which included passers-by harassing my coworkers on the streets of (normally very pleasant and friendly) Jinju. But no matter: whoever points it out, bloodlines-based nationalism is very much a thing in Korea (and Japan), and has led to such oddities as numerous apologies for and a national sense of guilt and shame over the actions of Virginia Tech shooter Seung-hui Cho in 2007, despite his having left South Korea at the age of 8 and absolutely no-one in the US considering him “Korean.”

Left: highly-recommended further reading (source: Stanford University Press). Right: “A BBC poll from 2016 of various countries, asking what the most important factor in self identity was. South Korea has the highest proportion given for ‘race or culture – 25%” (source: BBC via Wikipedia).

Left: highly-recommended further reading (source: Stanford University Press). Right: “A BBC poll from 2016 of various countries, asking what the most important factor in self identity was. South Korea has the highest proportion given for ‘race or culture – 25%” (source: BBC via Wikipedia).

♥

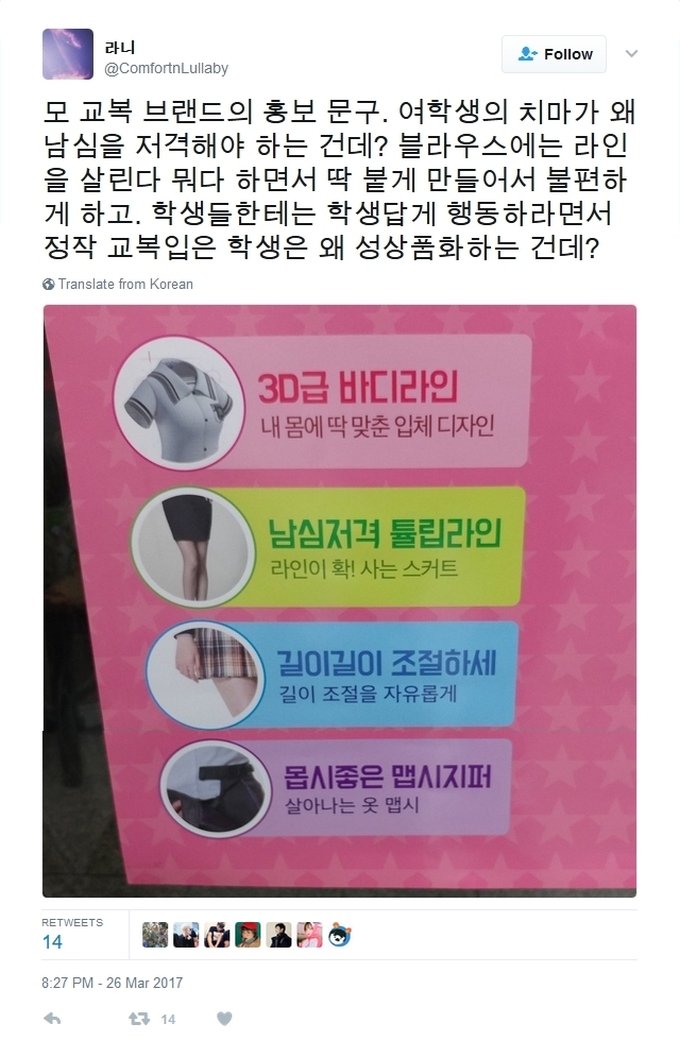

Next up, a week later, I was quoted by Diane Jean in “En Corée du Sud, les femmes n’ont pas d’autre choix que d’être belles” (“In South Korea, women have no choice but to be beautiful”) for ChEEK Magazine. As you can see it’s all in French, so here’s a bad translation of my contribution:

“Of course these pressures are not unique to Korea, they are found elsewhere,” says James Turnbull, a specialist in feminism and pop culture in Korea. But without having lived here, where, on a daily basis, your beautician, your teachers, your parents, your colleagues, your bosses constantly repeat to you that you have to go on a diet […], we can not realize how these pressures are particularly harsh for Korean women. “

That Korean women face body image issues will come as a surprise to nobody. But it can be difficult to convey their intensity, especially to overseas observers who are constantly bombarded with negative body image messages themselves. Probably most effective then, is to hear from the victims in person, especially overseas Koreans who frequently express their shock at the level of body-shaming they experience here compared to in their home countries. Listen to Korean-American Ji Eun-gyeong for instance, writing for Ilda South Korean Feminist Journal:

In contrast to the casual attire and revealing clothing of some of the Korean American women in the student program, Korean female students were uniformly slim, wore formal clothing to school, and always had perfectly groomed hair and makeup. I remember gawking at the female students wearing formal suits and heels at nearby Ewha University, something that was unheard of at schools in the US, where it was perfectly acceptable to go to school wearing pyjamas and looking like you rolled out of bed.

In comparison to these women, I was fatter, did not know how to put on makeup “properly,” and was relatively not well-groomed. The physical standards for Korean women were a palpable social pressure on me and the Korean American women, and despite our best efforts to “fit in,” we always fell short. We did not have the skills, energy, or time to put on full makeup, to dress formally for school everyday, nor did we have the slim body types that almost everyone around us seemed to have. Most importantly, we were not “well-behaved” women.

As Korean American women, we were unused to having so many restrictions on our movement and our bodies. One student in my exchange program was slapped for smoking in public, and another was yelled out for having lightly dyed hair. Others were reprimanded for wearing revealing or messy clothing, such as shorts with “holes” in them (shredded shorts). We talked too loudly and laughed too hard. Because of these and the daily judgments about our physical appearance that left us lacking, most of the women in our program felt a demoralized and degraded while we were in Korea. The policing of our bodies was limited to Korean Americans, because we were being compared to Korean women, while the foreign women were help up to different standards.

In contrast, the Korean American men in our program had less restrictions on their dress or their physical appearance. While they were subject to some pressures – ie, having clean-cut haircuts and not being able to wearing shorts – they were subject to less judgment about their bodies than the foreign women.

Admittedly she was writing about 1994, but you don’t need me to tell you that very, very little has changed for the next generation. That is also indicated by the following damning statistics, collected in these slides for my lecture on body image for my “Gender in South Korea” course at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies last summer:

Statistic from “Explaining Underweight BMI and Body Dissatisfaction among Young Korean Women” by Tess Hellgren (2012). Screenshot: “Street Interview – Are you fat? (Asking Korean girls)당신은 뚱뚱한가요? Nicki Minaj VS Yoona” by Joo Won.

Statistic from “Explaining Underweight BMI and Body Dissatisfaction among Young Korean Women” by Tess Hellgren (2012). Screenshot: “Street Interview – Are you fat? (Asking Korean girls)당신은 뚱뚱한가요? Nicki Minaj VS Yoona” by Joo Won. Statistic from: “18% of Young Women Found to Be Underweight“, anonymous, The Chosun Ilbo (2014).

Statistic from: “18% of Young Women Found to Be Underweight“, anonymous, The Chosun Ilbo (2014).

(Link to Georgia Hanias’s 2012 Marie Claire article in the slide, plus another one to an interesting critique.)

(Link to Georgia Hanias’s 2012 Marie Claire article in the slide, plus another one to an interesting critique.)

♥

Finally, there was one more interview after that, but I was completely edited out of the article when it was finally published last week. I’ll wisely spare you my rant though, only mentioning it as a final excuse for the delay in posting. So too, that I also did a long podcast interview in March, which will hopefully be coming out in the next couple of months.

Any thoughts? About any of the articles? :)

Related Posts:

- If You Don’t Have Kim Yuna’s Vital Statistics, Your Body Sucks and You Will Totally Die Alone

- Kim Yu-na, Yu-na Kim: Plato’s Perfect Skate: 김연아 Rocks!

- “Olympics Fairies”: Do the Faces of S. Korea Need to be Pretty Women?

- A Weighty Matter: Are Koreans Really Getting too Fat?

- A Weighty Matter: Deconstructing the Korean Media’s Messages about Body Image, Cosmetic Surgery, and Obesity

- Kim Yuna (김 연아) – sit back and soak it in

- Korean Sociological Image #7: The Best Gillette Could Get?

- Nationalizing the Balletic Body in Olympic Figure Skating

- Are Korea’s Women Boxers Good Enough for Adidas?

- Drama about female weightlifter criticized for lookism

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)