(Source)

(Source)

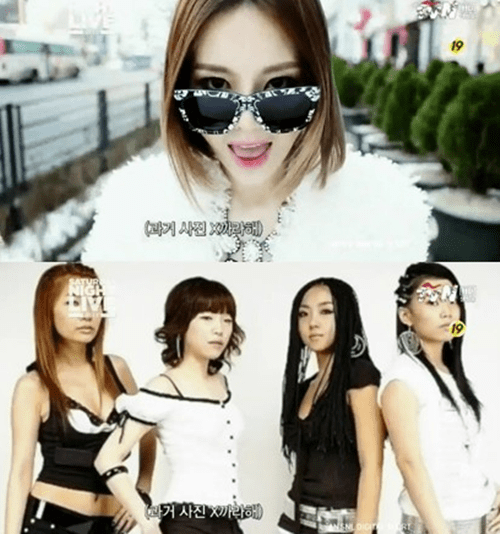

Frankly, all too many things come to mind when I see this picture of Girl’s Day from late-2010…but “Lolitas” isn’t one of them. Even if Haeri, second from left, did happen to be 16 at the time. Minah in the center, 17.

Fast-forward to March 2011 though, and the black leather, guitars, and bar setting of Nothing Lasts Forever would be ditched for uniforms and classrooms in Twinkle Twinkle, the sass for aegyo and pining after Oppa. By July, Girl’s Day would appear in the sickly-sweet Hug Me Once too, K-pop’s first music video to have a dating sim version.

Following on from Part 1, Part 2 of this blogger’s post is a very convincing account of this transformation over 2011, and makes you wonder how many fans they lost as a result (or, more cynically, how many more they gained). Also it takes little persuading to believe that many dating sims involve male characters selecting from a variety of youthful, even underage girls, and that it’s very telling that Girl’s Day would choose to replicate one.

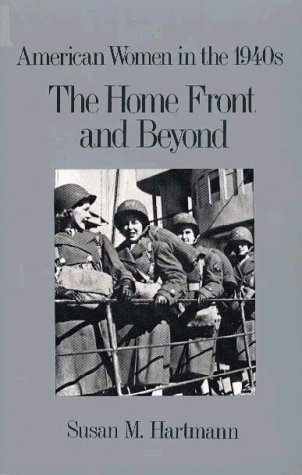

But really, it was their (now former) management company Dream T Entertainment that made the decision, so one criticism of the blogger is that he makes no distinction between the company and the group, despite members’ autonomy and consent being crucial for determining if they’re being sexually objectified or not (however, a dating ban and working conditions like these leave little doubt that they were indeed objectified). Another is his use of sweeping, take-his-word-for-it generalizations about lolicon and its popularity with otaku, which I’d wager readers familiar with Japanese popular culture will take issue with. Added to his sloppy, undefined, and interchangeable use of the terms “Lolita complex,” “Lolita syndrome” and the very rare “Lolitocracy” in Part 1, doing the same with a fourth Lolita-related term needlessly detracts from his arguments (source, right: author’s scan).

But really, it was their (now former) management company Dream T Entertainment that made the decision, so one criticism of the blogger is that he makes no distinction between the company and the group, despite members’ autonomy and consent being crucial for determining if they’re being sexually objectified or not (however, a dating ban and working conditions like these leave little doubt that they were indeed objectified). Another is his use of sweeping, take-his-word-for-it generalizations about lolicon and its popularity with otaku, which I’d wager readers familiar with Japanese popular culture will take issue with. Added to his sloppy, undefined, and interchangeable use of the terms “Lolita complex,” “Lolita syndrome” and the very rare “Lolitocracy” in Part 1, doing the same with a fourth Lolita-related term needlessly detracts from his arguments (source, right: author’s scan).

It was hypocritical of me to complain about a lack of definitions in Part 1 though, without providing my own. So, let me end this commentary here by offering what I took “The Lolita Effect” (which I think covers all the blogger’s related terms) to mean back at about the same time Dream T Entertainment decided to put it in action with Girl’s Day, based on my reading of the book of the same name by Meenakshi Durham:

…In short, it is the natural consequence of various industries’ (fashion, cosmetics, cosmetic surgery, diet-related, food, and so on) need to build, expand, and maintain markets for their products, which obviously they would do best by — with their symbiotic relationship with the media through advertising — creating the impression that one’s appearance and/or ability to perform for the male gaze is the most important criteria that one should be judged on. And the younger that girls learn that lesson and consume their products, the better.

Update 1 — Three things I should also mention:

1) Despite everything I’ve written about Girl’s Day, I’m hardly a hater, and I confess Female President is *cough* a bit of a guilty pleasure of mine, especially *ahem* that move at 0:51 in their performances (not so much in the MV though — their garish costumes put me off):

2) While they’re certainly sexually objectified in Female President, and likely will continue to be for their new mini-album to be released next week, it’s difficult to describe them as being portrayed as Lolitas now either. So, it appears further changes to their “concept” were made after the blogger wrote in August 2012, and I’ll investigate for a future post (can any fans provide any pointers?).

3) All that said, Nothing Lasts Forever just ROCKS (pun not intended), and is the only song of theirs I have on my MP3 player. If you haven’t heard it yourself, stop what you’re doing right now…then share my lament for Girl’s Day’s missed opportunity to stand out from most other girl-groups (and empathize with female indie groups that have to grapple with the same dilemma):

Update 2: For what it’s worth, leader and lead-vocalist So-jin recently expressed her discomfort with the group’s “cute concept.”

Taking up the translation directly where Part 1 leaves off:

(3) 걸스데이의 ‘MAXIM’ 화보 촬영 / Girl’s Day’s MAXIM Photoshoot

걸스데이의 성 상품화 방식은 반짝반짝 이후노래 뿐 아니라 다른 영역으로까지 확대된다. 그 중 대표적인 것이 걸스데이의 MAXIM화보촬영인데, 이러한 움직임은 걸스데이의 그룹전략이 성상품화 방식으로 흐르고 있다는 것을 극명하게 보여주는 사례가 된다. 걸스데이는 2011년 3월 반짝반짝 발매로 흥행을 거두고 있는 상태에서 걸 그룹 중 이례적으로 맥심(Maxim) 이라는 성인잡지에 모델로 출연하게 된다.

In addition to Twinkle Twinkle, Girl’s Day utilized a strategy of sexual objectification in many ways since. Out of these, their photoshoot for Maxim was both the most typical and most strongly demonstrated their shift in concept. They were chosen over other girl groups on the basis of the exceptional success of Twinkle Twinkle released in March.

맥심은 전형적인 성인 남성 잡지로 노출 수위가 높은 사진과 선정적인 내용을 담고 있는 잡지이다. 상반신이나 하반신을 의도적으로 노출시키는 포르노성 화보 뿐 아니라 특정 부분에서는 여성의 전라(全裸)의 신체가 노출되는 화보도 게재되고 있으며 그 내용도 선정적인 것이 많을 뿐더러 직접적인 성관계를 다루는 부분도 잡지 안에 상당부분 존재한다.

(Sources: left, right)

(Sources: left, right)

Maxim is a typical adult men’s magazine with an emphasis on pictures and sexual content. It doesn’t just have pornographic pictures with people’s upper or lower bodies willfully exposed, but publishes pictures of completely nude females and its contents deal mostly with lewd topics or are directly about sexual relationships. [James — I haven’t seen a copy in five years, but describing it as something akin to Playboy is a bit of an exaggeration surely? Either way, see here for pictures of the Girl’s Day shoot]

이러한 성인잡지에 10대 걸 그룹이 화보의 모델로 출연한다는 것은 사회적으로도 문제가 되는 일이었음에도 불구하고 걸스데이는 화보촬영을 감행한다. 2011년 5월호 maxim 속 공개된 걸스데이의 화보는 흰색 셔츠에 짧은 바지를 입어 ‘바지가 없는 듯한’ 설정의 컨셉, 소위 ‘하의실종패션’이라는 컨셉과 더불어 상반신 노출이 심한 의상과 선정적인 자세로 잡지에 실리었다. 그 당시 미성년자인 멤버가 둘(방민아, 이해리)이 있었음에도 불구하고 진행된 이 화보촬영은 성인문화의 중심인 성인잡지에 미성년자를 놓음으로써 롤리타 콤플렉스를 이용한 ‘미성년의 성’을 상품화한 극단적인 예라고 볼 수 있으며, 성 개방 풍조에 편승하여 ‘미성년의 성’을 상품으로 공략했다는 점에서 그전까지 노래에서 암시적으로 제시된 성 상품화 전략이 노골적으로 드러나는 부분이라고 볼 수 있을 것이다.

이러한 성인잡지에 10대 걸 그룹이 화보의 모델로 출연한다는 것은 사회적으로도 문제가 되는 일이었음에도 불구하고 걸스데이는 화보촬영을 감행한다. 2011년 5월호 maxim 속 공개된 걸스데이의 화보는 흰색 셔츠에 짧은 바지를 입어 ‘바지가 없는 듯한’ 설정의 컨셉, 소위 ‘하의실종패션’이라는 컨셉과 더불어 상반신 노출이 심한 의상과 선정적인 자세로 잡지에 실리었다. 그 당시 미성년자인 멤버가 둘(방민아, 이해리)이 있었음에도 불구하고 진행된 이 화보촬영은 성인문화의 중심인 성인잡지에 미성년자를 놓음으로써 롤리타 콤플렉스를 이용한 ‘미성년의 성’을 상품화한 극단적인 예라고 볼 수 있으며, 성 개방 풍조에 편승하여 ‘미성년의 성’을 상품으로 공략했다는 점에서 그전까지 노래에서 암시적으로 제시된 성 상품화 전략이 노골적으로 드러나는 부분이라고 볼 수 있을 것이다.

Although problematic, teenage members of Girl’s Day were included in the photoshoot for the May 2011 edition. Members dressed in white shirts and very short pants in a “disappearing pants” concept, which also excessively exposed their upper bodies and placed them in sexually suggestive poses. Using two underage members — Minah (17 years 11 months at the time of release; see above image), Haeri (16 years 10 months; above-right {source}) — in a photoshoot as the focus of an adult magazine is an extreme example of the Lolita complex, and shows that Girl’s Day were blatantly using it as a marketing strategy, rather than just hinting at it previously in songs and music videos.

Update 3: I forgot to mention that despite laws against it, Korean authorities have long turned a blind eye to sexualized images of minors in the media. Consider what I wrote about the marketing of Samaria/Samaritan Girl (2004) back in 2009:

Consider the two promotional posters above from 2004, featuring Kwak Ji-min (곽지민) and Han Yeo-reum (한려름) respectively. Never mind that Kwak is topless, and as a minor when the picture was taken, meant that it was technically illegal; as this case with a 14 year-old in January and this case with an 18 year-old earlier this month demonstrate, the Korean authorities still seem strangely reluctant to prosecute this sort of thing. Rather, the point is that far from discouraging one from having sex with minors, both posters seem to be positively encouraging it.

Continuing:

(4) ‘반짝반짝’ 이전 작품과의 비교 / Comparing Twinkle Twinkle to Girl’s Day’s Previous Works

이러한 걸스데이의 성 상품화 전략은 2011년 3월 ‘반짝반짝’이 나오기 전까지의 음악적 색깔과 ‘반짝반짝’이후의 음악적 색이나 성향이 어떻게 달라졌는지를 살펴보면 그 의도를 더욱 명확히 확인할 수 있다. 걸스데이의 초기 형태는 지금과 같지 않았다. 초기 활동 당시 여성 락 밴드를 표방하여 시작한 걸스데이는 새로운 멤버 교체 이후 ‘잘해줘봐야’라는 밴드 락 중심의 음반으로 활동하고 있었다. 가사의 내용 또한 제목에서 알 수 있듯이 반짝반짝과 이후 노래에서 볼 수 있는 풋풋한 사랑에 대해 다룬 것과 상반되게 배신과 복수를 다루고 있으며 강력한 비트와 단조 중심의 선율로 무거우면서도 강렬한 여성 락 그룹의 이미지를 보여주고 있었다. 멤버들의 의상 또한 강한 느낌의 노래와 어울리는 검은색 가죽옷과 팜므파탈적인 소품이 주를 이루었으며 클럽과 밴드 무대를 배경으로 한 뮤직비디오에서도 각 멤버는 있는 힘껏 드럼과 기타를 치거나 수화기를 세차게 던지거나 망치로 특정 대상을 치는 등 다소 과격하고 강한 느낌을 연출하고 있다.

If you compare Girl’s Day’s style of music before and after Twinkle Twinkle, their new sexual objectification strategy is clear. They are now very different to when they started. At the beginning, after the sudden membership changes, they emerged as a girl rock group with their song Nothing Lasts Forever. Rather than Twinkle Twinkle, which was about a new love, this song’s title and contents were about betrayal and revenge, with a rhythm in minor chords. The music video set in a bar with a stage in the background, the members give off a strong femme fatale vibe with their black leather clothes, their powerful working of guitars and drums, and hitting of hammers [James — inflatable hammers that is, but point taken about the very different vibe!] and violent throwing of phone receivers.

하지만 이러한 ‘잘해줘봐야’의 컨셉은 당시 걸 그룹의 기본적인 형태와는 상이한 것이었다. 그 당시 소녀시대와 원더걸스를 중심으로 ‘어리다’는 컨셉 하에 수많은 그룹들이 ‘어느 그룹에 평균연령이 더 어린가?’, ‘어느 그룹에 더 어린 멤버가 있는가?’로 경쟁하며 어리면서도 은근하게 성적으로 어필하는 능력이 인기 있는 걸 그룹으로 평가되는 시기였다.

However, at the same time that they had this concept, the standard for girl groups was very different. Centered around the Wondergirls and Girls’ Generation, they competed against each other and were judged on the basis of their youth (Which group had the youngest average age of members? Which group had the youngest member?), with an implicit sexual appeal on that basis.

기존에 존재하던 자기만의 음악적 색을 띠는 가수들은 브라운관 너머로 사라지고 ‘어림’과 ‘섹시함’이라는 다소 모순적인 가치를 얼마나 훌륭하게 배합한 걸 그룹들이 가요계를 점령하고 있었다. 이러한 상황에서 다소 성숙하고 반항적인 이미지의 걸스데이의 초기 컨셉은 이러한 흐름과는 상이한 매우 ‘이질적인’ 컨셉이었다.

In this environment, girl-groups with different styles soon disappeared from the airwaves, while those that focused on the (actually contradictory) combination of youth and sexiness soared ahead. Unfortunately, Girl’s Day’s original concept directly defied this trend.

하지만 이러한 이질성은 결코 강점이 되지 못했다. 문화산업의 시스템은 너무나도 확연하게 획일화를 요구하고 있었고 그 획일화에 순응하지 않는 그룹은 경제적인 무능력자가 되어 사라질 수밖에 없었다. 이러한 상태에서 걸스데이는 결국 데뷔 초기의 그룹 컨셉을 완전히 버리고 걸 그룹 문화의 거대한 양식의 흐름 편승할 수밖에 없었고, ‘반짝반짝’에서 완전히 새로운 컨셉으로 재탄생되게 된다. 거친 느낌의 가죽 자켓은 교복으로 바뀌었고 노래의 분위기는 천진하고 가볍게 변했다. 가사는 더 이상 반항을 말하지 않으며 순종적이고 연약한 소녀의 모습만을 그리게 된다. 이러한 이미지 변신을 시작으로 걸스데이는 안정적인 팬층을 확보하며 걸그룹시장내에 견고한 입지를 굳히게 된다.

This difference couldn’t be sustained. The culture industries demanded standardization, and groups that couldn’t adapt ultimately disappeared. Because of this situation, Girl’s Day had to completely do away with the concept they debuted with and join the girl-group bandwagon, coming up with the completely new concept of Twinkle Twinkle. The leather jackets were done away with in favor of school uniforms, the atmosphere now one of light naivete. The lyrics were no longer about rebellion, but stressed being meek, obedient, weak and frail girls. This image change helped give them a secure fanbase and cemented their entrance in the girl-group market.

이러한 걸스데이의 음악적 양상의 변화에 따른 인기의 변화는 ‘어린 이미지’가 걸 그룹 문화에서 얼마나 핵심적인 요소로써 작용하고 있는가를 잘 보여주는 것이다. 비록 멤버들 중 어린 멤버가 있다고 할지라도 그 멤버가 성적 어필을 하지 않는 컨셉인 ‘잘해줘봐야’같은 노래는 대중들의 관심을 끌 수 없다. ‘반짝반짝’처럼 ‘미성년의 성’을 직접적으로 다루고 언급하는 노래만이 대중 걸 그룹 문화에서 살아남을 수 있다. 위에서 살펴본 이러한 면들은 걸 그룹에 팬들이 반응하는 이유가 그들의 ‘미성숙한 성’에 있는 것이라는 사실을 보여주며 이것이 현 걸그룹 문화의 거대한 흐름이라는 사실을 잘 보여주고 있다.

This [successful] change by Girl’s Day demonstrates that a girl-groups must have a youthful image at their core in order to survive. Also, despite having adolescent members in their group, the lack of sex appeal in Nothing Lasts Forever [James — I beg to differ; he means a Lolita-like sex appeal] meant that it went unnoticed by the media — only songs like Twinkle Twinkle that directly refer to or take advantage of teenage sexuality will gain attention. They are also the only kinds of songs that get a reaction from fans, and, combined, demonstrate how strong this trend is.

(Sources: top, middle, bottom)

(Sources: top, middle, bottom)

<사진 2> 위 두 사진은 걸스데이의 반짝반짝 이전과 이후 스타일이 얼마나 크게 변화했는지 보여준다. 맨 왼쪽 사진은 ‘잘해줘봐야’ 활동 당시 모습으로 락 밴드 느낌의 강하고 터프한 이미지로 활동했음을 잘 보여준다. 중앙 사진은 ‘반짝반짝’의 컨셉사진으로 ‘girl’s day school’이란 마크와 교복을 변형한 형태를 통해 그룹 멤버의 ‘어린’ 이미지를 강조한 모습한다. 두 컨셉의 변화는 롤리토크라시의 양상으로의 변화가 잘 드러난다.. 세 번째 사진은 ‘한번만 안아줘’의 컨셉사진으로 하얀 드레스와 순백의 배경으로 ‘잘해줘봐야’와 완전히 상반되는 ‘여성성’을 강조하는 컵셉을 기반으로 하고 있다. 걸스데이는 ‘반짝반짝’의 흥행성공으로 걸스데이는 완전히 방향을 전환하여 기존 컨셉을 버리고 ‘어린 이미지’와 ‘미성년의 여성성’을 강조하는 이미지로 탈바꿈하였다. (사진출처: “걸스데이”, 구글)

Caption: These three pictures show the evolution in Girl’s Day’s style. In the first from Nothing Lasts Forever, they give off the image of a strong, tough, rock band. In the middle, a concept photo for Twinkle Twinkle, the new emphasis on members’ youth with the “Girl’s Day School” banner and school uniforms can be seen. Finally, with Hug Me Once, the complete transformation from Nothing Last Forever is evident, with a virgin-white background and dresses and an emphasis on women’s sexuality. Twinkle Twinkle was such a hit that Girl’s Day completely did away with their old image, and instead stressed a youthful image and adolescent girls’ sexuality.

(5) 걸스데이의 ‘한번만 안아줘’ / Girl’s Day’s Hug Me Once

이러한 양상은 이후 2011년 7월 ‘반짝반짝’ 이후 연이어 출시된《Everyday》의 타이틀곡 ‘한번만 안아줘’에서 완전히 고착화되었음을 보여준다. 제목에서부터 다소 자극적인 느낌의 이 곡은 걸스데이의 음악이 완전히 ‘잘해줘봐야’의 컵셉에서 ‘반짝반짝’의 컨셉(즉, 귀엽고 깜찍하지만 또 한편으로는 성적인 어필을 하는 컨셉)으로 전환되었음을 보여주는 곡이다. 이 곡에서는 이전 ‘반짝반짝’에서처럼 직접적인 미성년에 대한 암시, 즉 교복이나 학교 같은 컨셉은 취하고 있지 않지만 뮤직비디오와 가사에서 아동성애적인 장치를 충분히 보여주고 있다.

Girl’s Day’s adherence to this new concept in Twinkle Twinkle was confirmed in their follow-up song Hug Me Once, the title-track to their second mini-album everyday — from the title to the music, it clearly gives off the same feeling of cuteness and preciousness on the one hand, and sex appeal on the other. Although it lacks the school uniforms and school-like setting of Twinkle Twinkle, the music video and the lyrics still hint towards adolescent sexuality through a variety of devices.

이 곡에서 특히 뮤직비디오가 상당히 특징적이다. 최초로 시도된 3개의 개별화된 뮤직비디오는 공식 발표 3일전 세 개의 뮤직비디오를 암시하는 intro 티져 영상을 통해 공개되어 많은 사람의 주목을 받았다. 3개의 뮤직비디오는 ‘한번만 안아줘’라는 하나의 곡을 가지고 3가지 다른 타입, Dance ver, Game ver, MV로 이루어져 있다. 감상자는 DVD의 영상선택방식을 이용하여 화면을 마우스로 클릭하여 다른 모드의 뮤직비디오를 시청할 수 있다. 이러한 뮤직비디오 방식은 이전까지 전무했던 뮤직비디오 양식이었다는 점에서 언론에 많은 관심을 받았으며 매우 획기적이라는 평가를 받게 된다.

The music video was also groundbreaking, and gained a lot of attention in the media, as three days before the official release, a teaser video hinted that there would be three versions: a dance version, a game version, and a typical music video. Viewers would be able to select between them and within each via menus and clicking options like when using a DVD.

여기서 우리가 주목할 것은 세 개의 뮤직비디오 중 Game version이다. Game version은 3개로 뮤직비디오를 분할한 것만큼이나 매우 실험적이고 도전적이었는데, 그 이유는 뮤직비디오의 Game ver이 일본 애니메이션 산업에서 파생한 ‘연예시뮬레이션’ 게임의 양식을 따랐다는 점에서이다.

(Sources: top, bottom)

(Sources: top, bottom)

Out of the three, the game version was the most noticeable and challenging to make, as it derived from a “dating sim” [lit. “Lovers’ simulation”] model used in the Japanese animation industry.

[연애 시뮬레이션 게임은 연애를 모방한 게임 장르의 하나로, 코나미에서 제작된 도키메키 메모리얼 시리즈에 근본을 두고 있다. 주로 주인공이 남성이고 연애 상대로 미소녀들이 등장하므로 미소녀 연애 시뮬레이션이라고도 한다. 대한민국에서는 이 말을 줄여서 미연시라는 용어를 만들었는데, 이 용어는 원래 뜻을 넘어서 미소녀 게임을 총칭하는 말로 쓰이고 있다. 이러한 연예시뮬레이션게임은 일본의 만화, 애니메이션 문화와 함께 발달하여 1차원적 감상에서 벗어나 만화 캐릭터와 실제로 상호작용 함으로써 “세계와 삶에 대한 종합적 체험을 갖는 것이 이제 불가능한 상태에서 오직 시각적인 체험의 형식”으로 경험이 가능한 오타쿠 문화에 주체의 의식을 반영할 가능성을 제시한 산업이다. [(김홍중, 심보선, 실재에의 열정에 대한 열정,한국문화사회학회, 문화와 사회, 제4권 2008.5, pp.114-146 )]

The dating sim genre is derived from the Tokimeki Memorial series by Konami. In them, the subject is usually male, the object of his affections female, and often underage; in Korea the name for such games has been shortened to mi-yeon-shi, and has come to encapsulate all games involving underage characters. Building upon Japanese comics, animation books, and the otaku culture industry it goes beyond passive viewing to an interactive experience with the characters, “giving a more holistic, lifelike experience, which changes the impossible to a visual form” [James — Apologies, but I found the second half of this paragraph exceptionally difficult; this is my best guess]. (Kim Hong-joong and Shin Bo-seon, “The Passion of the Passion of the Real: The Poetry and Poetics of Miraepa,” Culture and Society, The Korean Association for the Sociology of Culture, Volume 4, May 2008, pp. 114-146.)

Game ver 뮤직비디오는 잠에서 깨어난 1인칭 시점의 화자가 걸스데이 멤버 한명 한명과 여러 장소를 이동하며 데이트를 한다는 내용으로 구성되어 있다. 뮤직비디오는 시작부터 ‘insert coin’이라든지 게임등급표시 등의 표시를 넣어 게임임을 강조하는데 뮤직비디오 전 프레임에 ‘연예시뮬레이션’게임에 사용되는 겉 테두리와 사각형의 말 상자 그리고 새로운 캐릭터가 등장할 때마다 팝업(pop up)되는 간략한 신상소개 상자 등은 완전히 뮤직비디오의 내용을 연예시뮬레이션게임에서 차용했음을 보여주는 면이다. 뮤직비디오의 주인공, 1인칭 대상은 손과 발만 노출하여 각 멤버들과 손을 잡거나 함께 걷는 등의 모습을 보이는데 이것은 간접체험으로써의 한계를 극소화 시키려는 연예시뮬레이션의 ‘비매개’의 속성을 이용한 흔적이라고 볼 수 있을 것이다. 그리고 5명의 멤버와의 데이트가 끝나게 되면 화면이 바뀌면서 5명의 멤버중 한명을 고르라는 선택화면이 나오게 되는데 이러한 설정 또한 연예시뮬레이션의 요소를 그대로 가져왔다고 볼 수 있다. 이 마지막 화면은 또 5개의 개별엔딩으로 구성되어 있어 감상자의 선택에 따라 개별엔딩으로 연결된다.

The game version of the music video is told from a first-person perspective, in which the viewer goes on separate dates with each member of Girl’s Day in a variety of different locations. It uses many elements common to dating sims, including: the use of an “insert coin” text; a frame or border around the screen; pop-up speech bubbles with simple introductions to the members; and only having the subject’s hands and feet visible, making his presence indirect but also more realistic. Another borrowed element is having a screen with all five members appearing at the end, with different endings [to each date] appearing depending on which member is selected.

James — Compare the June 2009 Tell Me Your Wish by Girls’ Generation, the group most strongly associated with the Lolita effect in Korea:

여기서 주목할 점은 이 뮤직비디오의 양식을 단순히 재미있는 뮤직비디오 아이디어로 보기 힘들다는 점이다. 왜냐하면 뮤직비디오가 차용한 일본 연예시뮬레이션 게임이 오랜 시간동안 ‘롤리타 콤플렉스’의 해소처, 즉 로리콘 문화의 중심으로 간주되어왔다는 사실 때문이다.

It is difficult to dismiss the music video as simple fun, for the lovers’ animation genre it so heavily borrows from has long been considered the natural home of the Lolita complex, and a natural fit with lolicon comics.

James — Given that natural fit, I expected to find a great deal of academic sources that discussed both, but to my surprise didn’t find any at all. Can any readers fill in the gaps? Lacking any expertise myself, I’m wary of relying on media sources that tend to have a “The Crazy, Perverted Japanese” undercurrent to them, but on the other hand it’s true that I can’t think of many other countries where events like this would ever happen, even if foreign media outlets do exaggerate their popularity.

연예시뮬레이션게임은 주로 애니메이션에서만 등장하는 캐릭터를 게임화시킴으로써 사용자와 상호작용할 수 있게 한다는 것이 게임의 취지이다. 사용자는 캐릭터를 사용자의 주체적인 내러티브에 집어넣음으로써 캐릭터와의 개별적인 경험을 형성함으로써 현실에서 만날 수 없는 미소녀와 연애를 함으로써 대한 대리 만족을 경험하게 한다. 연애시뮬레이션 게임은 그렇기에 현실에서 접하기 힘든 어린 미소녀를 주 대상으로 삼아왔으며 일본 로리콘 문화에 핵심적인 산업으로 자리 잡게 된다.

The purpose of dating sims is for the viewers to interact with ‘gameized characters, and to give them independent narratives and experiences with them. The underage characters are a proxy for something they are unable to have in real life, and are why lovers’ animation games are at the core of the Japanese lolicon comics industry.

(“TV 아사히, 3차원 미소녀 아이돌 vs 2차원 미소녀 캐릭터? / TV Asahi, 3rd level underage idols vs. 2nd level underage characters?” — just some of the unfamiliar terminology I had struggle with here! Source)

(“TV 아사히, 3차원 미소녀 아이돌 vs 2차원 미소녀 캐릭터? / TV Asahi, 3rd level underage idols vs. 2nd level underage characters?” — just some of the unfamiliar terminology I had struggle with here! Source)

그런 점에서 연예시뮬레이션게임의 모델을 뮤직비디오에 차용했다는 사실은 단순히 뮤직비디오의 재미를 위해 제작하였다고 보기는 힘들게 만든다. 연예시뮬레이션 게임이 로리콘 문화에서 2차원의 어린 캐릭터와 상호작용하기 위한 욕망을 기반으로 만들어졌다는 점을 기억할 때, 뮤직비디오의 제작자가 이러한 요소를 인지하지 못한 채 뮤직비디오를 만들었다고 보기는 힘들다. 결국 이러한 점을 종합해 보면 ‘한번만 안아줘’의 뮤직비디오는 로리콘 문화와 같은 방식으로 ‘미성년에 대한 성애적 욕망’에 호소하여 성을 상품화하는 전략이라고 볼 수 있으며, 또한 뮤직비디오를 통해 그러한 문화에 익숙한 대중들, 즉 로리콘 문화에 익숙한 소위, ‘오타쿠’들을 직접적인 소비자로 설정하여 성 상품화하려는 제작자의 의도가 드러난다고 볼 수 있다.

In that regard, it is difficult to describe it as a simple music video. Also, when you remember that dating sims and lolicon comics are produced to stimulate interaction with and sexual desire for fictional underage characters, it is difficult to believe that the producer was unaware of that. In the end, by using elements similar to those in lolicon comics in the music video for Hug Me Once, and calling for a sexual objectification strategy based on sexual desire for underage girls, it is apparent that this music video was produced for the direct consumption of those most familar with lolicon comics, the otaku.

이러한 뮤직비디오의 구성과 더불어 곡 자체에서도 앞선 ‘반짝반짝’에서처럼 미성년임에도 성적인 어필을 하는 많은 부분을 발견할 수 있다.

Along with these elements, Hug Me Once shares many with Twinkle Twinkle that are based on a sexual appeal of underage girls.

‘한번만 안아줘’의 가사는 A-B-C-A-B-C-A-D 형태로 ‘한번만 안아줘’라는 말이 반복적으로 A 부분과 D부분에서 사용되고 나머지 가사의 내용 전개는 B와 C를 중심으로 이루어진다. 가사 B의 부분에 ‘한번만 안아보면 내 맘을 알 텐데 뛰는 내 가슴은 여기 시계보다 더 빠른데’ 라는 부분은 앞선 ‘반짝반짝’의 예에서처럼 모순적인 감정의 미성년을 드러내어 단순히 부끄러움 때문에 표현하지 못하는 것일 뿐 “어린 소녀도 욕망의 주체”라는 사실을 표현함으로써 수용자에게 사회적 억제기제에 대한 정당화의 구실을 제공한다. 또한 이후 바로 이어지는 ‘한번만 안아줘’로 구성된 반복적인 부분은 조르는 듯 한 애교 섞인 말투이지만 또 이성 간에 스킨십을 적극적으로 바라는 욕망을 표현한다는 점에서 어린 이미지와 성적인 주체로써의 이미지를 혼합함으로써 롤리타적 욕망을 자극하는 모습을 보이고 있다.

The lyrics to Hug Me Once follow an A-B-C-A-B-C-A-D form, “Hug Me Once” repeated in the A and D parts and the remainder concentrated in the B and C parts. In the B part, they read “If you hug me once, you will know my feelings [desires], my heart is beating faster than a clock,” an ironic, contradictory combination of desire and embarrassment at and/or inability to act on it, which removes societal constraints on relationships with minors by encouraging the [adult, male] viewer to  take the initiative. Also, the “Hug me Once” parts are said with such aegyo that the combination of opposite-sex skinship, and sexual and youthful images provided must be viewed as directly playing to a Lolita-like desire (source, right).

take the initiative. Also, the “Hug me Once” parts are said with such aegyo that the combination of opposite-sex skinship, and sexual and youthful images provided must be viewed as directly playing to a Lolita-like desire (source, right).

And that ends Part 2. Part 3, which I’ve left to an awesome, wonderful reader who generously offered to translate it, will be up next Monday. Until then, Happy New Year!

Related Posts:

• Consent is Sexy, Part 3: Female President by Girl’s Day #FAIL

• Korean Girl Rockers, Defying the Stereotypes

• Ajosshis & Girls’ Generation: The Panic Interface of Korean Sexuality

• What did Depraved Oppas do to Girls’ Generation? Part 1

• “Cleavage out, Legs in” — The Key to Understanding Ajosshi Fandom?