Whatever your motivations for learning Korean, this YouTube audiobook channel is an amazing resource!

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes.

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes.

So, last week I played in the Korean National Chess Championships, coming 9th out of 62 (I came 2nd in 2019; just saying). The next day, I started a new semester, teaching a brand new “Sociology through Science Fiction” class in addition to my “Introduction to Korean Gender Issues” one. The day after that, I hit the one month-mark into dating someone simply amazing who lives in another city—which suddenly feels so close, and yet so frustratingly far. And then yesterday, I turned 50.

I wasn’t intending such a slow comeback sorry. But as excuses go, that combination is pretty hard to beat.

You could say the same thing about my date’s intelligence, personality, and appearance too. Out of respect to her though, as well as to your preferred topics, that’s the last thing I’ll mention about her for a while.

The last thing that is, except for her major being Korean language and literature. And, that on the day she told me, my Google Alert for “페미니즘” (feminism) sent me an article about author Kang Bo-ra winning the novel category in the Hankook Ilbo‘s Literary Contest for her short story “In Tinian,” with the theme of the intractable hypocrisy and double-standards surrounding “young women’s sexual desire.” Which, of course, I just had to send her a link to immediately. Because how better to impress a woman I hadn’t even met yet, than suddenly talking about sex? Right?

But seriously, she was interested. Too interested. She asked insightful questions, which I couldn’t immediately answer. Before I knew it, I realized I was going to have to actually read the short story itself if I was going to pull this totally fake persona off.

Rude.

Fortunately, it was available online. Unfortunately, I hate reading on devices, especially reading Korean. And this story especially felt rather flat in translation.

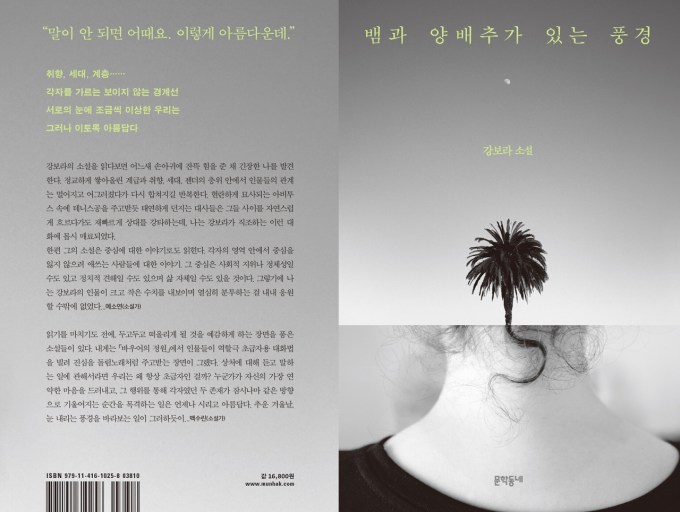

Fortunately again though, yes, Google Alerts really did send me a five-year old article that day. Because last year, Kang published her short story collection 뱀과 양배추가 있는 풍경 (Landscape with Cabbages) with “In Tinian” as the first chapter. Needless to say, I had a copy by the next day.

Still, something felt missing.

And that, dear readers, is the story behind how I came across the YouTube channel 아름다운 소리책방 (lit. “Beautiful Audiobook Room”), where the selfless narrator (I don’t think it’s AI) reads out literally hundreds of Korean short stories and novels for you:

For someone like me, not a fan of mainstream Korean dramas and films, and whose Korean ability patently suffers from that, it’s a real game-changer. I hope it’s as transformative and helpful for you too.

But I’d be remiss if not finishing by passing on a little more information about “In Tinian” itself, whatever your own motivations for reading it—and maybe listening too!

First, here’s a summary of it from a brief review by Pyeon Seong-jun, from his brunch blog about books (brunch is like a Korean version of Substack):

사이판에서 가까운 섬 티니안으로 3박4일 여행을 떠난 중학교 동창 수혜와 민지의 이야기다. 그들은 거기서 ‘펫맨’과 ‘리틀보이’라는 미국 남자들을 만나는데 알고 보니 그 이름은 히로시마와 나카시마에 떨어졌던 두 개의 원자폭탄 이름에서 따온 짓궂은 농담이었다. 이 섬은 태평양전쟁의 격전지였고 원자폭탄들을 보관했던 ‘맨해튼 프로젝트’ 기지였던 것이다. 민지는 처음 보는 미국 남자들 앞에서 스스럼없이 수영복 상의를 벗고 노는 수혜가 못마땅하다. 그러면서 한창 성욕이 왕성했고 그 욕망에 충실했던 중학교 시절 ‘걸레 삼총사’라 불리며 전교에서 따돌림과 폭행을 당했던 수혜와 나, 그리고 연선을 떠올린다. 갑자기 ‘증발’해버린 연선과 그들이 함께 나누었던 비밀 일기장의 마지막 페이지를 궁금해하면서.

This is the story of [former] middle school classmates Su-hye and Min-ji, who embark on a three-night, four-day trip to Tinian, an island near Saipan. There, they meet American men named “Fay Man” and “Little Boy,” whose names, it turns out, were a mischievous pun derived from the two atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nakashima. The islands were a fierce battleground during the Pacific War and a base for the Manhattan Project, where the atomic bombs were stored. Min-ji, [the narrator], is displeased with Su-hye’s brazen stripping off her swimsuit in front of these American men, whom she’s never met before. She then recalls how Su-hye, herself, and [a third girl called] Yeon-seon were bullied everyone during their middle school years, when their sexual desires were at their peak, and how they were nicknamed the “Slut Trio.” She comes to wonder about Yeon-seon’s sudden disappearance and the final page of the secret diary they shared.

And with my apologies to Pyeon, my intention was to offer a variety of perspectives on the short story, and I do try to avoid copy and pasting everything Korean content creators write when offering my translations of their work here. But his thoughts alone were just too good not to offer them in their entirety:

읽어보니 작가 강보라는 ‘어린 여성의 성욕’에 대해 써보고 싶었다고 한다. 신춘문예의 소재로는 다소 위험해 보이기도 하는데 막상 읽어보면 적당한 등장인물들의 효과적인 배치는 물론 실감 나는 대화와 과감한 생략 등을 통해 주제의식을 훌륭하게 형상화하고 있다.

Reading the acceptance speech, Kang said she wanted to write about “young women’s sexual desire.” While it might seem like a risky topic for a spring literary contest, the novel masterfully embodies its thematic message through its effective characterization, realistic dialogue, and bold omissions.

But let me interrupt briefly by expanding upon that point with Kang’s own words, taken from an anonymous interview in Elle magazine (and which is also worth reading in its entirety):

2021 한국일보 신춘문예 소설 부문에 당선됐다. 수상 소감 기사의 제목이 ‘어린 여성의 성욕, 페미니즘의 가장 구석진 자리에 대해 쓴 소설’이던데 학창시절에 ‘쟤 노브라래’ ‘남자친구랑 어디까지 갔대’ 같은 자잘한 소문에 시달린 기억이 있다. 어린 여자애였기에 부당하게 겪는 루머들. 마흔 살이 된 지금 웃으며 이야기하지만 그런 시선들이 지금 나의 성적 관념을 만드는 데 일조하지 않았을까 싶긴 하다. 그래서 저 기사 타이틀이 부담스러웠을지언정 부끄럽지는 않았다.

I won the 2021 Hankook Ilbo Spring Literary Contest in the fiction category. The title of my acceptance speech article was “A Novel About Young Women’s Sexual Desire and the Cornerstones of Feminism.” I remember being plagued by petty rumors during my school days, like, “She’s braless,” and “How far did you go with your boyfriend?” Rumors I was unfairly subjected to as a young girl. I laugh about it now, in my forties, but I wonder if those gazes contributed to my current sexual perceptions. So, while the title of the article may have been burdensome, I wasn’t ashamed.

Finally, back to Pyeon’s thoughts:

소설 말미에 주인공 민지는 중학교 시절 호기심으로 자신과 몸을 섞은 뒤 자신을 걸레 취급했던 남자들의 SNS를 뒤지며 ‘그들이 좀 불행했으면 좋겠다는 인간적인 바람’을 슬쩍 고백하기도 한다.

소설은 ‘영혼이 자유로운(사실은 몸에 헤픈)’ 여자애들을 바라보는 남성들의 꼰대스러운 시각과 그게 그렇게 나쁜 건가?라고 되묻고 싶어하는 여성들의 심리를 여러 가지 상황이나 메타포를 통해 전달하는데 특히 섬에서만 볼 수 있는 나무 플레임 트리에 대한 묘사나 – 약한 바람에도 새빨간 꽃잎을 폴폴 날리는 아름답지만 헤픈 나무 – 여행이 끝나갈 때쯤 민지가 느꼈던 황량함을 묘사하는 문장이 – 사흘간의 여행이 나만 못 알아들은 농담처럼 느껴졌다 – 너무 좋았다. 하다못해 섬에 와서 다큐멘터리를 찍는 ‘썬글라스’ 남자의 “그러고 보면 역사란 거대한 아이러니의 텍스타일인 것 같아요.”라는 멋 부린 대사 바로 뒤에 “저 밥맛은 뭐래.”라고 비웃는 수혜의 속삭임을 붙인 것조차 너무 귀여웠다.

게스트하우스 주인이나 다큐멘터리 제작자들의 걱정과는 달리 전날 미국 남자들과 번갈아 키스를 나누던 수혜가 결국은 아무 일 없이 돌아오는 장면 처리가 좋았고 돌아오는 경비행기 안에서 두 친구가 헤드셋을 부딪히며 웃는 장면은 통쾌했다. 오랜만에 읽어본 신춘문예 당선작이었는데 느낌이 좋아서 짧게라도 리뷰를 남겨보고 싶었다. 그래서 썼다. 다시 말해 추천한다는 얘기다, 이 멋진 단편소설을.

Toward the end of the novel, Min-ji, out of curiosity, searches the social media accounts of the men who treated her like a slut after having sex with her in middle school, and even subtly confesses her “human wish that they were a little unhappy.” The novel conveys the old-fashioned perspective of men regarding “free-spirited” (but really meaning “slutty”) girls, and the psychology of women who want to question whether that’s really such a bad thing, through various situations and metaphors.

I particularly enjoyed the description of the flame tree, a tree found only on the island—a beautiful yet slutty tree that flutters its bright red petals even in the slightest breeze—and the sentence describing Min-ji’s sense of desolation toward the end of the trip—which made the three-day trip feel like a joke I couldn’t understand—was especially captivating. Even the way Su-hye whispers, “What does that food taste like?” right after the stylish line from the “Sunglasses” man who came to the island to film a documentary: “Come to think of it, history seems like a vast textile of irony,” was incredibly cute.

Contrary to the concerns of the guesthouse owner and the documentary producers, the scene where Su-hye, who had been taking turns kissing American men the day before, ultimately returns without incident was well-handled, and the scene where the two friends clink headsets and laugh on the light plane on the way back was exhilarating. It had been a long time since I read a winning work in the Spring Literary Contest, and I loved it so much that I wanted to leave a review, even if it was brief. So I wrote this review. In other words, I heartily recommend this wonderful short story. (End.)

Image sources: Aladin, NamuWiki.

As I also did to my date, of the last Korean novel I featured here: Bodies and Women ‘몸과 여자들’ by Lee Seo-su. An intimate discussion of beauty ideals, gender socialization and body-shaming in schools, sexual assault, pregnancy, sex in marriage, pervasive sexual objectification, and the male gaze, she immediately borrowed my copy once we did meet, and had devoured it within a day. Before I know it, she’ll surely be wanting to talk about that too.

Is this what dating is like in 2026? Clearly, she has an eager eye for everything this guy can offer her. At 50 now though, how am I ever going to keep up with her insatiable demands? Arrgh!

Related Posts:

- I’m Ready to Pay for Korean Feminist Films!

- “저의 몸과 저의 섹슈얼리티에 대한 이야기를 해보려고 합니다. 이것은 실로 부끄러운 고백이어서 저는 단 한 번밖에 말하지 못할 것 같습니다. 그러니 가만히 들어주세요.”

- Korean High School Girls Complain They Can Barely Breathe in Uniforms Smaller Than Clothes for 8-Year-Olds.

- 노출이 강간 유혹?…허튼소리 말라 Wearing Revealing Clothes Leads to Rape? Don’t Be Absurd

- Single Korean Women are Being Scammed into Paying More to Feel Safe in Their Homes. You Don’t Have to be a ‘Feminist’ to Acknowledge That.

- Free The Nipple in Korea? Why Not? Uncovering the history of a taboo

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)