Even university students are astonished at how short and restrictive they’ve gotten.

Estimated reading time: 12 minutes. Photo by Noah Buscher on Unsplash.

Estimated reading time: 12 minutes. Photo by Noah Buscher on Unsplash.

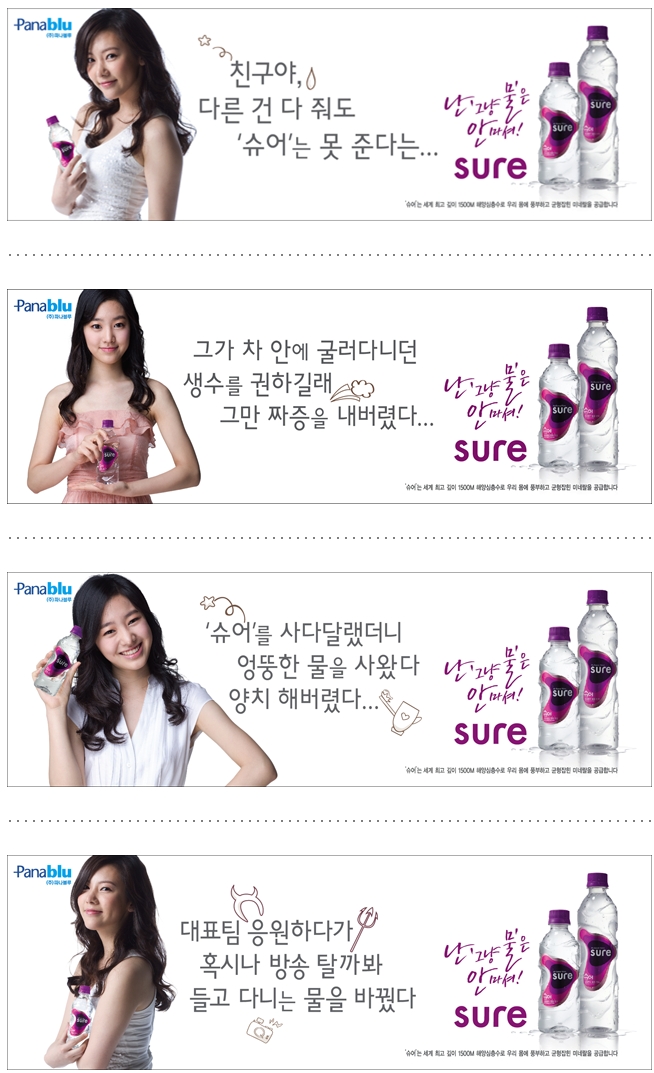

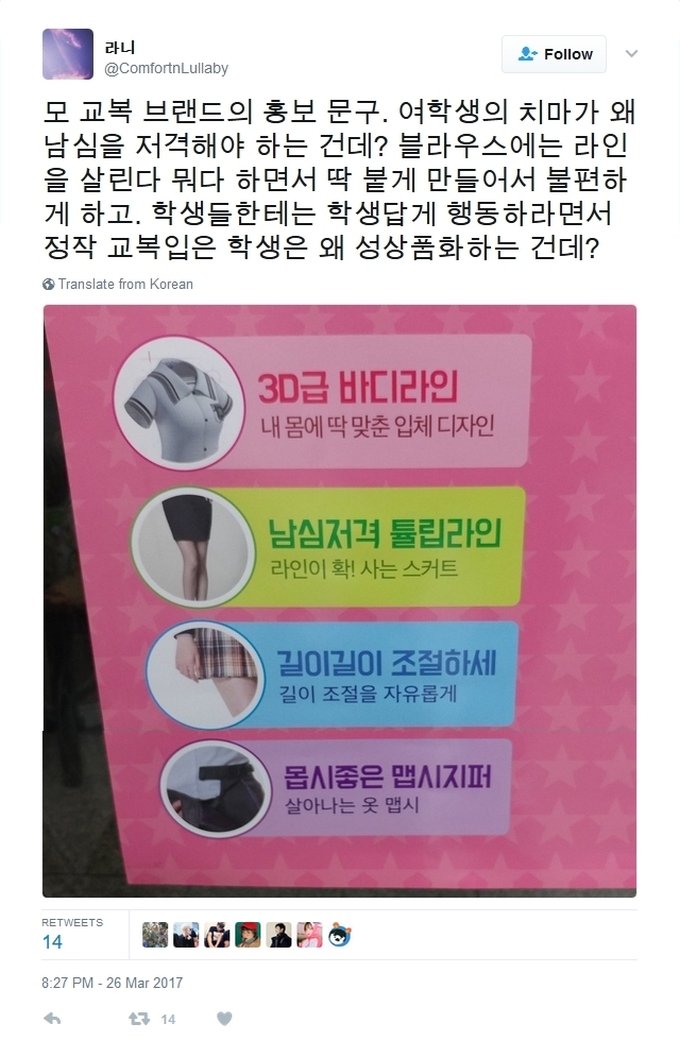

Ten years since I first wrote about it, I’m still astounded that K-pop stars can endorse school uniforms. Surely, much of the blame for Korea’s notorious issues with female body image can be laid squarely on K-pop and school uniform companies’ shoulders? Those same companies that tell 12-year-old girls entering middle school that their new uniforms will help them show off their tits and ass to boys?

Left: Victoria Song of f(x) showing off her ‘S-line’ in 2009 (Source unknown). Right: Eun-ha of GFriend in 2016; middle caption says “The ‘Tulip Line’ skirt that will immediately capture men’s hearts” (Source: MLBPARK).

Left: Victoria Song of f(x) showing off her ‘S-line’ in 2009 (Source unknown). Right: Eun-ha of GFriend in 2016; middle caption says “The ‘Tulip Line’ skirt that will immediately capture men’s hearts” (Source: MLBPARK).

But things may not be so one-sided as they may seem. At the end of her must-read March 2017 post “Time to Stop Skirting the Issue: Sexualization of School Uniforms in South Korea,” Haeryun Kang noted in Korea Exposé that:

Tighter uniforms have been popular among boys and girls for years. A recent survey of over 9,000 teenagers showed that students from elementary to high school generally preferred uniforms that were slightly tighter and shorter. In the debate surrounding the sexualization of teen uniforms, the voices of teenagers themselves is conspicuously absent.

In my own post “How Slut-Shaming and Victim-Blaming Begin in Korean Schools” too, published on the same day (hey, great minds think alike), I noted that being able to wear more fashionable clothes had also been directly tied to the liberalization of students’ rights. Plus, students the world over have generally always wanted to improve upon their drab uniforms. Once the sexualization of their uniforms began in earnest here a decade ago then, there would undoubtedly have been many girls who genuinely wanted to wear the tight, figure-hugging styles promoted by K-pop stars, and probably often despite the objections of their parents and teachers too. To assume they were simply dupes of the uniform companies instead would be incredibly naive and misguided, let alone patronizing.

Alas, the survey mentioned by Kang is likely unreliable, as it was conducted by a school uniform company itself. But her conclusion still stands: listen to teenagers themselves. Don’t assume.

When you do, you discover what girls are saying these days is that they can’t breathe in their uniforms. That they hate them. That wearing them is having serious effects on their learning, well-being, and physical health. That they’re angry. That rather than being a reflection of their wishes, having such limited clothing choices imposed on them is actually an infringement of their rights.

In other words, generally the complete opposite of what the schools and the uniform companies would like them to. Wow—teens don’t like being told what to do. Who’d have thought?

Let’s hear from some of those teens, starting with those interviewed in the following June 2018 MBC News Today report. Appropriately enough, it’s opened by everyone’s favorite news anchor Lim Hyeon-ju, who also didn’t like being told what to do—in March that year she’d become the first Korean female news anchor to wear glasses on the job, and later would go on to be the first to appear without a bra:

My translation of the transcript:

숨도 못 쉬는 여학생 교복…”인권침해 수준” Uniforms Girls Can’t Breathe in…”An Infringement on my Human Rights.”

Anchor

여자는 치마에 블라우스, 남자는 바지에 셔츠. 중·고등학교 교복에 적용되는 흔한 규정인데요. 그런데 요즘 여학생들 사이에서는 치마 대신 바지를, 블라우스 대신 편한 셔츠를 입게 해달라는 요구가 끊이지 않고 있습니다. 그 속사정을 서유정 기자가 취재했습니다.

Girls wear a skirt and a blouse, boys wear pants and a shirt. This is a common rule regarding middle and high school uniforms. Nowadays however, there are constant calls from girls to likewise be able to wear more comfortable shirts and pants. Reporter Seo Yoo-jeong covers the story.

Reporter

단추도 채워지지 않는 블라우스, 숨 쉬는 게 힘겨울 정도로 꽉 조여진 허리라인. 20대 여성들이 카메라 앞에서 중·고등학교 교복을 입고 힘겨워합니다.

Blouses so tight that all the buttons can’t be done up, waistlines that make it difficult to breathe. In front of the camera, women in their 20s are struggling to wear middle and high school uniforms.

[김서윤] “숨을 못 쉬겠어요. 단추를 하나만 더 풀게요.”

[Kim Seo-yoon] “I can’t breathe. I’ll just undo one more button.”

[정겨운] “이런 걸 입고 하루에 12시간 이상을 산단 말이에요? 이건 진짜 인권 침해인데.”

[Jeong Gyeo-woon] “You mean you have to live wearing these things for more than 12 hours a day? This is a real human rights violation!”

요즘 여학생들의 교복 블라우스가 얼마나 작고 불편한지를 눈으로 보여준 이 영상은 조회수 20만 건을 넘기며 인터넷을 뜨겁게 달궜습니다.

This video, which shows how small and uncomfortable girls’ school uniform blouses are these days, has already received more than 200,000 views. [James—Its contents will be covered in more detail later below.]

요즘처럼 날이 더워질수록 교복에 대한 여학생들의 불만은 더해갑니다.

As the days get hotter with the summer, girls’ complaints about their school uniforms will only increase.

기자가 입어보니, 기성복으로 나온 교복을 줄이지 않고 입었는데도 블라우스는 치마 허리선을 아슬아슬하게 덮을 정도로 짧습니다. 손을 들면 맨살이 그대로 드러날 정도입니다. 통은 더 좁게, 길이는 더 짧게.

This reporter tried on an off-the-shelf uniform. Yet even though it was not shortened, the blouse only barely covered the waistline of the skirt. When I raised my hand, the bare skin of my waist was exposed. [Compared to the uniforms I wore as a girl], the waist is narrower and the length is shorter.

학교에서 정한 대로 교복업체는 디자인을 맞춰줄 뿐이라고 합니다. [◇◇교복 업체 관계자] “학교의 원래 원칙은 짧아서 이게(허리선이) 보여야 했어요. 그걸 저희가 이번에 길게 뺀 거예요.”

It is said that school uniform manufacturers [generally] only produce designs as determined by the schools. [Anonymous school uniform manufacturer] “Even though your midriff got exposed when you raised your hand, in fact the original school’s design for this blouse was even shorter. We lengthened it.” [James—Consider the implications for sexuality equality in classroom interactions and discussions when the girls’ clothes alone ensure they’re too embarrassed to even raise their hands!]

“이런 불만은 ‘교복을 없애달라’, ‘여학생들도 바지나 남자 셔츠를 입게 해달라’는 국민청원으로까지 이어지고 있는 상황. 이런 요구를 받아들여 남녀구분 없이 ‘편한 교복’을 입게 하는 학교들도 조금씩 생겨나고 있습니다.

The ensuing dissatisfaction is leading to national petitions calling for girls to be able to wear boy’s uniforms, or to do away with school uniforms entirely. Schools that accept these demands and have allowed boys and girls to wear ‘comfortable uniforms’ are also slowly emerging.

서울의 한 고등학교는 봄 가을엔 헐렁한 후드 티를, 더운 여름엔 반바지와 면 티셔츠를 교복으로 입습니다. [김현수/고등학교 1학년] “팔도 더 잘 올라가고 그러니까 생활하기도 더 편해요. 집중하기 더 편한 것 같아요.”

[Kim Hyeon-su, first year student at this high school] “I can raise and move my arms much more easily, so I have a better quality of life. I think it’s easier to for me to concentrate too.” One high school in Seoul allows baggy hoodies to be worn in the spring and autumn, and shorts and cotton t-shirts in the hot summer.

옷값을 줄이고, 공동체 의식을 갖게 하는 교복의 긍정적인 기능은 살리되, 성별에 따라 복장을 규정하고 움직임에 불편을 주는 폐단은 버리자는 취지입니다/

With these comfortable uniforms, the school’s goal is to retain the good points of school uniforms such as the reduction in the cost of clothes and the fostering of a sense of school community, while also doing away with defining uniforms by sex and removing any features that make it difficult to move freely. (End)

Next, adding to the point about exposed waists especially, here are some segments from a March 2018 CBS No Cut News report by Gwon Hee-eun:

“슬림핏 교복 두려워요” 여학생들 교복 공포증 “I’m afraid of slim fit school uniforms”: Girls’ School Uniform Fears

…여학생들이 입는 하복 셔츠는 짧은 기장 탓에 책상에 엎드리면 셔츠가 훤히 올라가 맨살이 드러나는 것은 물론, 가만히 있어도 속옷이 비칠 정도로 얇다.

…Because of the short length of the summer blouses, they rise up and reveal girls’ skin when they bend forward while sitting at their desks. They are also thin enough to reveal the outlines of underwear even while the girls are sitting still.

이때문에 보통 하복 셔츠 안에 민소매나 반팔 티셔츠를 덧대어 입는 것이 일반적이다. 어떤 학교에서는 이를 ‘교칙’으로 지정해두기도 할 정도다. 더 단정해 보인다는 이유에서다.

Then 16 year-old Jeon Somi endorsing Skoolooks, here wearing their ‘Slim-line Jacket.’ Source: Somiracle – Jeon Somi 전소미 Vietnam Fanpage.

Then 16 year-old Jeon Somi endorsing Skoolooks, here wearing their ‘Slim-line Jacket.’ Source: Somiracle – Jeon Somi 전소미 Vietnam Fanpage.

For this reason, it is common to wear a sleeveless or short-sleeved T-shirt underneath a summer blouse. Some schools have even incorporated this into their uniform codes, believing it looks neater. [James—Assuming this rule only applies to girls, this means they would swelter under blouses, bras, and t-shirts in summer classrooms, compared to boys enjoying just one layer. See my earlier post to learn more about many more discriminatory rules like this.]

여학생들의 교복이 과하게 짧고 작아 불편을 초래한다는 사실은 여러 차례 지적돼 왔다. 그러나 교복업체들은 여전히 날씬해보이는 ‘슬림핏’을 마케팅 포인트로 내세운다.

It has often been pointed out that girls’ uniforms are uncomfortable and inconvenient because of their small size and short length. However, promoting this ‘slim fit’ is at the heart of school uniform companies’ marketing strategies.

교복 광고 속 날씬한 여자 아이돌들은 타이트한 자켓과 짧은 치마를 완벽하게 소화해낸다. 하루에 열시간 넘게 교복을 입는 학생들에게는 그런 완벽한 ‘슬림핏’이 불편하다.

In school uniform advertisements, slim female K-pop idols perfectly fit into their tight jackets and short skirts. However, they are uncomfortable for [real-life] students [with a much wider range of body types] who have to wear them for more than 10 hours a day.

최근 유튜브에서 눈길을 끈 ‘교복입원프로젝트’ 영상을 보면 이런 문제는 더 적나라하게 드러난다.

The extent of the problem becomes readily apparent when you see the following video from the ‘School Uniform Hospitalization Project,’ which has recently attracted attention on YouTube [as seen in the first report].

(Not by FemiAction, but this later video by RealCafe of boys trying on girls’ uniforms is also interesting and amusing)

‘불꽃페미액션’이 제작한 이 영상에는 여섯명의 여성이 등장해 실제 여학생 교복 상의와 아동복 사이즈를 비교하고, 직접 착용해보기도 한다.

In this video, produced by Fireworks FemiAction, six women appear, compare the sizes of actual school uniform tops and children’s clothes, and try them on.

여학생용 교복셔츠와 남학생용 교복셔츠를 비교해봤더니, 여학생용 교복셔츠가 훨씬 비침이 심했다. 여학생용은 글씨 위에 셔츠를 겹쳐도 글씨를 바로 알아볼 수 있는 반면, 남학생용은 다소 시간이 걸렸다.

When the boys’ shirts were compared with the girls’ blouses, the uniform shirts for girls were much more see-through. For girls’ blouses, things with writing on them hidden underneath were immediately able to be made out. Whereas with boys’ shirts, it took some time.

키 170cm, 가슴둘레 94cm 기준인 여학생 교복 셔츠와 7~8세용 15호 아동복 사이즈를 비교해보니 가로 폭은 별 차이가 없었고, 기장은 아동복보다 훨씬 짧았다.

When comparing the size of a school uniform blouse for girls with a height of 170cm and a chest circumference of 94cm to a casual size 15 t-shirt intended for girls between 7-8 years old, there was no difference in width, and the length was much shorter than that of the t-shirt.

활동성이 전혀 고려되지 않은 사이즈로 만들어졌다 보니, 머리를 묶거나 팔을 뻗는 등의 동작도 하기 어렵다.

Blouses of this size don’t take any activity or movement into account, so it’s difficult to tie your hair or stretch your arms.

이렇듯 많은 학생들이 아동복보다 작은 교복으로 불편함을 겪고 있지만, 학교 내에서 체육복 등 편한 옷으로 갈아입고 있는 것도 허용되지 않는다.

…[The article continues by saying that students would prefer changing into their more comfortable gym uniforms, but this is generally only allowed in exceptional circumstances such when their regular uniform is torn or has food spilt on it.]…

(Update: As reported by The Korea Bizwire in June 2020, an ironic side-benefit of the Covid-19 Pandemic has been that schools have become more relaxed about this, allowing students to wear their gym uniforms on days they have physical education classes at school. The logic is that allowing them to wear them for the entire day reduces physical contact with other students while changing.)

실생활에서 불편함을 느끼는 학생들이 꾸준히 문제제기를 하고 있지만, 교복 판매업체의 정책과 각 학교의 교칙 등 여러 가지가 얽혀있는 사안이라 명확한 해결책이 나오지 않고 있다.

Students who feel uncomfortable in real life are constantly raising problems, but there are no clear solutions due to issues that are intertwined with the policies of school uniform vendors and school rules of each school. (End)

Source: Pixabay.

Source: Pixabay.

Finally, some segments of a July 2017 report by Son Ho-yeong for The Chosun Ilbo:

여고생에 ‘8세 사이즈’ 입어라… 숨쉬기 힘든 S라인 교복 Uniforms for High School Girls are Smaller than Clothes for 8 Year-Olds…S-line Uniforms that Make Breathing Difficult

서울 양천구의 한 여고에선 교복 블라우스를 ‘배꼽티’라고 부른다.… 이 학교 정모(17)양은 “교복에 몸이 갇힌 느낌”이라고 했다.

In one girls’ high school in Yangcheon-gu, Seoul, school uniform blouses are called ‘crop tops’….One 17-year-old student there said, “I feel trapped in my school uniform.”

…상당수 학교가 맵시를 강조하면서 허리선을 잘록하게, 길이는 짧게 디자인한 교복을 채택하고 있다. 보통 몸매인 학생들도 조금만 움직이면 속옷과 맨살이 훤히 드러나 제대로 활동하기 어렵다. 체형이 통통한 학생은 꽉 끼는 교복 때문에 수치심을 느끼는 경우도 있다. “교복 때문에 학생들의 인권이 침해받는다”는 소리가 나올 정도다.

…Many schools have adopted school uniforms designed to be short and with narrow waistlines, while emphasizing style. Yet their tightness means that students with average bodies find it difficult to study properly because their underwear and bare skin are exposed if they move a little, with larger than average students feeling even more anxious. [Indeed], you could go so far as to say school uniforms are violating their human rights.

예전 교복은 활동성을 고려해 펑퍼짐한 스타일이 많았다. 학생 일부가 멋을 내느라 치마 길이를 줄이고, 허리선을 강조하는 식으로 수선했다. 요즘은 처음부터 교복이 몸에 달라붙게 나온다. 늘이기는 어려운 디자인이다. 자신의 실제 몸 치수보다 큰 것을 사도 사정은 다르지 않다. 서울 종로구의 한 여고생은 “겨울 교복보다 두 치수나 큰 여름 교복을 샀는데도 허리의 ‘S라인’이 지나치게 들어가 밥을 먹고 나면 옷이 끼어 거북하다”고 했다.

With older school uniforms, there were many styles that were both flattering and didn’t hamper movement. [Naturally however,] some girls would shorten their skirts and emphasize their waistlines to look more attractive. Yet these days, school uniforms cling to the body from the beginning, and are difficult to stretch. Compensating by buying larger sizes may not even help either. One high school girl in Jongno-gu, Seoul said, “I bought a summer school uniform that is two sizes larger than my winter school uniform. But the ‘S-line’ on the waist is too overdone, and after I eat my clothes still start clinging to my body.”

A 2003-2005 school uniform advertisement featuring BoA; I’m unsure who the boy/man is sorry. See many more examples from then here.

A 2003-2005 school uniform advertisement featuring BoA; I’m unsure who the boy/man is sorry. See many more examples from then here.

날씬한 맵시만 강조하다 보니 여고생 교복 치수가 8세 아동복 수준이 되기도 한다. 서울 강북구의 한 인문계 여고 교복 상의(키 160㎝·88 사이즈)와 시중에 판매 중인 7~8세 여아용 티셔츠(130 사이즈)를 비교했더니 크기 차이가 거의 없었다.

As they emphasize only slim fit styles, the size of school uniforms for high school girls is the same as casual clothes for 8-year-olds. There was little difference in size when comparing a school uniform top (160cm tall, size 88) for girls in a school in Gangbuk-gu, Seoul and a t-shirt for girls aged 7-8 years old (size 130) sold at the local market.

2016년 기준 우리나라 여고생의 평균 키는 160.6㎝, 8세인 초등학교 1학년 여아 평균 키는 120.5㎝이다.

As of 2016, the average height of high school girls in Korea was 160.6 cm, and the average height of a 8-year-old girl entering elementary school was 120.5 cm.

교복은 기성복과도 차이가 있다. 한국산업표준(KS)에 따르면 키 160㎝인 여성 청소년의 ‘보통 체형’용 기성복 상의(블라우스 기준)는 가슴둘레 88㎝, 허리둘레 72.8㎝이다. 본지가 구한 여고 교복 상의의 가슴둘레는 78㎝, 허리둘레는 68㎝였다. 교복이 기성복 가이드라인보다 가슴둘레 10㎝, 허리둘레는 5㎝가량 작다.

School uniforms are also different from ready-made clothes. According to the Korean Industrial Standard, a 160cm tall female adolescent’s non-uniform, off the shelf, blouse-like top for a ‘normal’ body type has an 88cm chest and 72.8cm waist. Yet the waist circumference of a girls’ high school uniform blouse obtained for this report had an 78 cm and a 68cm waist, meaning that school uniforms are about 10 cm shorter in chest circumference and 5 cm in waist than required by the standards for off the shelf clothes.

일부 여학생은 교사의 단속을 피해 남학생용 교복을 사서 입기도 한다. 대전 서구의 한 남녀공학 고교에 다니는 이모(16)양은 “남학생용 교복은 라인이 없어 편하다. 학생주임 선생님이 남자 교복을 입지 못하게 수시로 단속하지만 몰래 입는 친구가 많다”고 했다.

For the sake of comfort and to avoid unfair school rules regarding girls’ uniforms, some wear boys’ school uniforms instead. One 16-year-old girl who attends a coeducational high school in Seo-gu, Daejeon, said, “The school uniform for boys is comfortable because there is no figure-hugging ‘line’ built into them. Although our teachers regularly crack down on this, many of my female classmates secretly wear them.”

교복 브랜드의 ‘슬림 라인’ 전쟁은 2000년대 초부터 시작됐다. 멋을 위해 교복을 줄이는 학생들이 늘면서 교복 제조업체들이 허리가 쏙 들어가고 길이가 짧은 디자인의 교복을 내놓기 시작했다. ‘재킷으로 조여라, 코르셋 재킷’ 같은 광고 문구를 내세웠다.

The ‘Slim Line’ war of school uniform brands began in the 2000s. As more and more students want more fashionable uniforms, manufacturers have responded by offering short designs with tight waists. In their advertising, they use phrases such as ‘Tighten with a jacket, corset jacket.’

…교복 업체가 사람마다 다른 체형을 고려하지 않는 것도 문제다. 한 업체는 체형 데이터를 바탕으로 청소년 ‘대표 체형’을 뽑아내 이를 기준으로 교복을 만든다고 광고한다. 하지만 이는 ‘보기 좋은 체형’일 뿐 해마다 몸이 변하는 청소년들에게 일률적으로 제시하는 것은 무리다.

Another problem is that school uniform companies do not cater to different body types. One company advertises that it makes a school uniform based on the ‘representative body type’ based on data collected about young people’s physiques. However, this supposedly representative type is really only a stereotypical ‘good looking body type’ [like that of the K-pop stars in the ads], nor does a single type take into account the fact that adolescents’ bodies are constantly changing. (End)

Photo by 周 康 from Pexels

Photo by 周 康 from Pexels

Thoughts? Still not enough? If so, I recommend also watching Dr. Kyunghee Pyun’s (Fashion Institute of Technology, State University of New York) presentation for the UBC Centre for Korean Research on “Impression Management of School Uniform Culture in Korea,” which I was able to attend on Zoom a few days ago. While it’s only loosely related, and covers much earlier time periods, it does provide some useful context:

Also, and finally, for a more recent and in-depth look, here is an 8-minute, November 2020 report by my local Busan MBC, ironically at one point filmed where I took this related, well-discussed picture. Unfortunately, producing a transcript and translation would be a bit prohibitive sorry, but the English CC seems to provide the gist. Enjoy!

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)

Related Posts:

- How Slut-Shaming and Victim-Blaming Begin in Korean Schools

- Being Able to Wear Glasses Was a Crucial Step for Korea’s Anchorwomen. Now, Let’s Give Them a Chance to SPEAK as Much as Anchormen Too

- Korean Sociological Image #55: School Uniform Advertisements

- Korean Lolita Nationalism: It’s a thing, and this is how it works

- Hyundai Fit-Shaming Korean Girls

- Time to Stop Skirting the Issue: Sexualization of School Uniforms in South Korea (Korea Exposé)

Estimated Reading Time: 5 minutes. Source:

Estimated Reading Time: 5 minutes. Source:

Sources:

Sources: