Turning Boys Into Men? Girl-groups and the Performance of Gender for South Korean Conscripts, Part 7

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes. Source, right (cropped): Streetwindy via Pexels.

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes. Source, right (cropped): Streetwindy via Pexels.

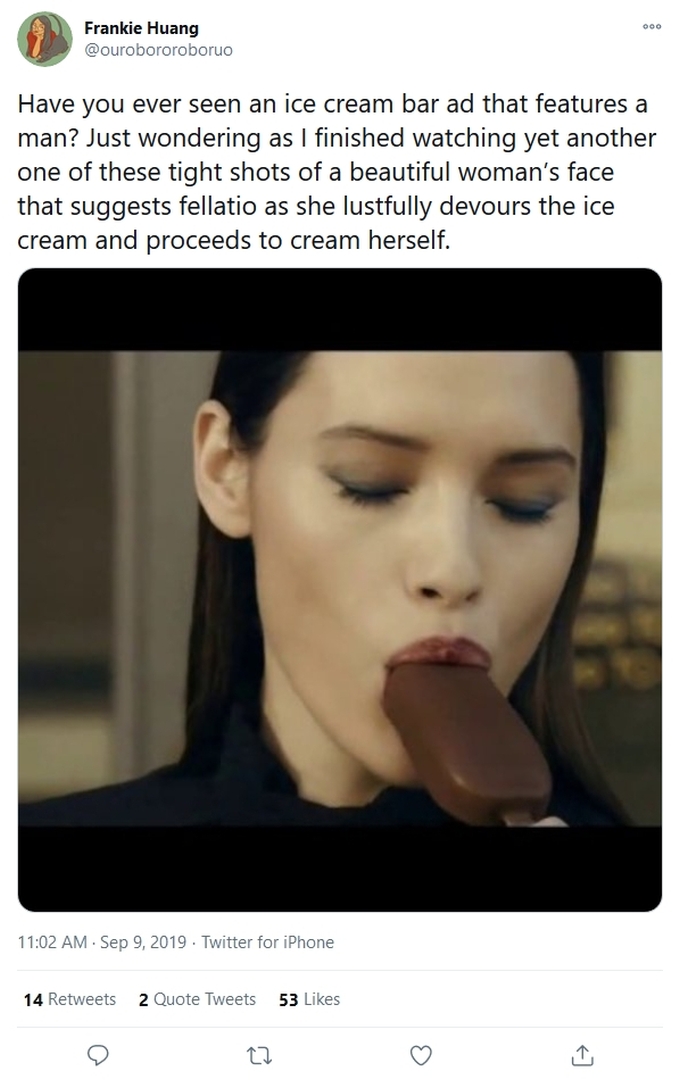

The contents of Everyday Sexism (2014) by Laura Bates, a UK-focused collection of public submissions and statistics on the myriad of ways women experience sexism on a daily basis, will be depressingly familiar to anyone who already considers themselves a feminist. Having accidentally ordered the book though, I could hardly not read it. Besides, I reasoned, what cishet middle-aged white guy wouldn’t still have a lot to learn about the topic?

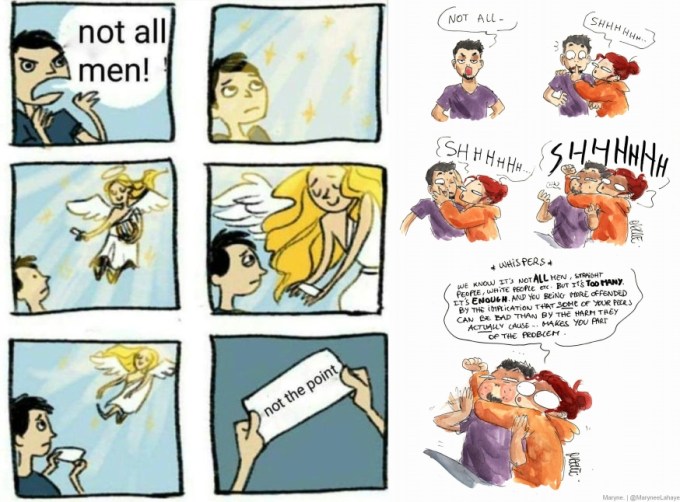

So I persevered. And sure enough, there were many things which gave me pause, especially the accounts of sexual harassment experienced by female university students. Partially, because I’d been blissfully unaware of that sort of thing when I was a student myself. Primarily though, because they strongly reminded me of an incident at the “morale-raising” YG Military Festival held in Yanggu County in Gangwon Province on 5 October 2019, at which the female university students hired to be doumi (lit. “help-elegant-beauties”) were forced to wear revealing clothes for the soldiers. From the news reports below, which discuss that in the context of how routine it is to provide sexualized performances by professional performers and/or K-pop girl-groups at such events, it’s easy to see how choices like these can encourage a somewhat objectified, servile view of women among the (usually) very young, impressionable Korean men that go through the male conscription system. Many do overcome that socialization experience, of course. But the consequences for all Koreans of those that don’t would fill many, many chapters in a Korean version of the Everyday Sexism book.

Screenshot, SBS News.

Screenshot, SBS News.

My translated excerpts of various reports about the incident, starting with one from Wikitree:

YG 밀리터리 페스타는 양구군이 장병들 사기 진작을 위해 지난해부터 개최한 것이다. 이벤트 경기, VR 체험, 먹거리 시장, 가수 공연 등이 열린다. 네일 케어, 피부 관리, 타로점 등 체험 부스도 있다. 이번 축제에는 육군 2사단과 21사단 장병 2300여 명이 참가했다.

The festival has been held since [2018] by Yanggu-gun to boost morale among soldiers, featuring competitive games, VR experiences, food stalls, and performances by singers and girl groups. There are also “experience booths” [really stalls/tables] for nail care, skin care, and tarot readings. This year, about 2,300 soldiers from the 2nd and 21st Divisions attended the festival.

논란은 체험 부스에서 일어났다. 머니투데이에 따르면 행사 대행업체 측이 행사장으로 가는 버스 안에서 여자 알바생들에게 흰색 짧은 테니스 치마와 몸에 달라붙고 가슴 부분이 파인 옷을 제공했다. 알바생들은 “속옷이 비치고 노출이 심한 옷이었다“, “조금만 움직여도 가슴이 훤히 드러났다“라고 전했다. 이어 “행사 담당자는 ‘군인들이 쑥스러워하니 직접 데려오라‘, ‘군인들에게 적극적으로 대하라‘고 지시했다“라는 말도 덧붙였다. 이들은 피부 관리 부스에서 군인들에게 직접 마스크팩을 붙여주는 일을 했다.

The controversy took place over the experience booths. According to Money Today, on the bus going to the venue the event agency provided the female part-time workers with only short white tennis skirts and tight-fitting, lowcut tops to wear. The women complained, “They were so tight you can see my underwear through them,” and “Even if I moved only a little, my chest would be completely exposed.” They added, “The event manager instructed, ‘As the soldiers will be embarrassed, [especially those wanting you to put [skincare-type] facemasks on them], please approach them proactively and encourage them as you escort them into the booths.”

Some additional information from that report by Money Today:

알바생 A씨는 “사전에 알려준 의상보다 더 파이고 조금만 움직여도 배가 드러날 정도로 상의 길이가 짧았다“며 “알바생들이 속옷이 비치고 노출이 심해 민소매 티셔츠를 요청했지만 아무 조치가 없었다“고 주장했다. 일부 알바생은 노출이 부담스러워 따로 챙겨온 외투를 걸쳤다고 한다.

One part-time worker complained that, “The clothes were much shorter and tighter than what we were told about, exposing my stomach even if I moved just a little,” and that “Even though we asked for sleeveless t-shirts because our underwear was visible, nothing was done about it.” It is said that some of the workers wore a separate coat over the clothes because of embarrassment.

…

행사 대행업체 측은 “요즘 학생들이 많이 입는 테니스 치마일 뿐“이라며 “일부러 노출이 심한 의상을 제공한 것이 아니다“라고 해명했다. 행사 스태프는 여성이 25명, 남성이 15명 정도였는데, 대행업체 측은 “원래 남자 직원들은 힘쓰는 일을 주로 하고 여자 직원은 차를 따라주는 등 행사 도우미 역할을 맡는 관행을 따랐을 뿐“이라고 설명했다.

A person from the event agency responsible for the clothes said, “It was just a tennis skirt like many students wear these days,” and that “We did not provide any clothes deliberately designed to overexpose the workers’ bodies.” They further explained that 25 women and 15 men were hired, but that “It’s customary that men have to do a lot of hard work, whereas women just have to be helpers and do things like pouring tea.”

Confusingly, in the video of the event above, many doumi can be seen wearing other clothing, which is not addressed by the anchors in the brief SBS News segment below that. Yet why should they? Whether through chance, smarts, and/or previous experience with doumi companies, that some of the women had alternate clothes on hand doesn’t negate the fact that those without had no other options.

Professional entertainment group Waveya (not a K-pop group) performing at a middle school in 2012.

Professional entertainment group Waveya (not a K-pop group) performing at a middle school in 2012.

On the other hand, if it’s the norm to hire young women in high-waisted skirts and low-cut tops for just about anything in Korea, including performances at schools, then the comment about no additional exposure being intended may well be true, if somewhat obtuse. That being said, I’m just as confused as you as are as to how men putting up tables and chairs somehow justifies forcing women to wear revealing clothes while serving tea. It’s also frustrating that the reporter didn’t challenge that non-explanation.

Policing the Student Body: Sookmyung Women’s University students told to cover up

Policing the Student Body: Sookmyung Women’s University students told to cover up

I see reason for optimism though, in that the issue of consent was the hook that made the incident newsworthy, especially given that this must-read by a professional doumi gives the strong impression that such incidents are routine. Had I been writing a news report myself, I might have continued by comparing students’ own festivals and events, which also regularly create controversy for their sexual overtones, but, crucially, at which the offending clothes are worn by choice. (Or perhaps not necessarily; the ensuing sensationalist reports are hardly deep, and now Everyday Sexism compels me to reconsider them.) However, the main reason for the news reports was more likely the harm caused to the military’s image, Asiae raising in their own report another controversial incident that occurred at a different military festival the year before:

지난해 8월14일 유튜브에는 ‘피트니스 모델 @군부대 위문공연‘이라는 제목의 영상이 올라왔다. 영상 속 피트니스 모델은 각선미를 강조하는 등 자극적인 동작을 선보였다.

해당 공연 사회자가 “지금부터 기본포즈 4가지를 보여드리겠다“며 자세를 요구하자 선수는 뒤돌아서 엉덩이를 뺀 자세로 머리를 넘겼다.

또 “나이가 어떻게 되냐“는 사회자의 질문에 “21살입니다“라고 답하자 장병들의 환호가 이어졌다.

On August 14 [2018], a video titled “Fitness Model @ Military Consolation Performance” was posted on YouTube by the military. The model’s dance was quite sexualized, involving showing off body parts like her legs. At one point, she proclaimed “I will show you four basic poses now,” turning around to thrust her buttocks at the audience with her head down, her face visible underneath. To the cheers of the men watching, she answered “I’m 21!” when they loudly asked her age.

해당 영상을 접한 누리꾼들은 “여성 성상품화가 지나쳤다“, “위문공연을 꼭 이런 방법으로만 해야 하냐“며 분통을 터뜨렸다.

또 당시 청와대 국민청원 게시판에는 “성상품화로 가득찬 군대위문공연을 폐지해주세요“라는 제목의 글과 함께 해당 영상이 첨부되기도 했다.

Netizens who saw the video on YouTube were angered, commenting that “The sexual objectification of the woman was excessive,” and questioning if such sexualized dances “were really the only way morale boosting performances could be done?”. Later, citing the video, a petition to abolish precisely those was posted on the Blue House’s public petition bulletin board [which the government has to respond to if it receives more than 200,000 signatures].

파문이 커지자 해당 부대는 영상을 삭제 조치했다. 부대는 “당시 공연은 민간단체에서 주최하고 후원한 것으로 부대 측에서는 공연 인원과 내용에 대해 사전에 알 수 없었으나, 이번 공연으로 인해 ‘성 상품화 논란‘이 일어난 데 대해 사과의 말씀을 드린다“고 했다.

그러면서 “앞으로 외부단체에서 지원하는 공연의 경우에도 상급부대 차원에서 사전에 확인하여 유사한 사례가 재발하지 않도록 하겠다“고 덧붙였다.

As the controversy grew, the military unit that uploaded it deleted the video. A spokesperson said, “As the performance was organized and provided by a private company, we could not have known what the contents would be. Nonetheless, we apologize for the “controversy over sexual objectification” this performance has caused. They added, “To prevent recurrences in future, we will check the contents of performances provided by external organizations in advance.”

Here’s part of the offending video, a blurred news report about it and other similar performances, and an unblurred compilation:

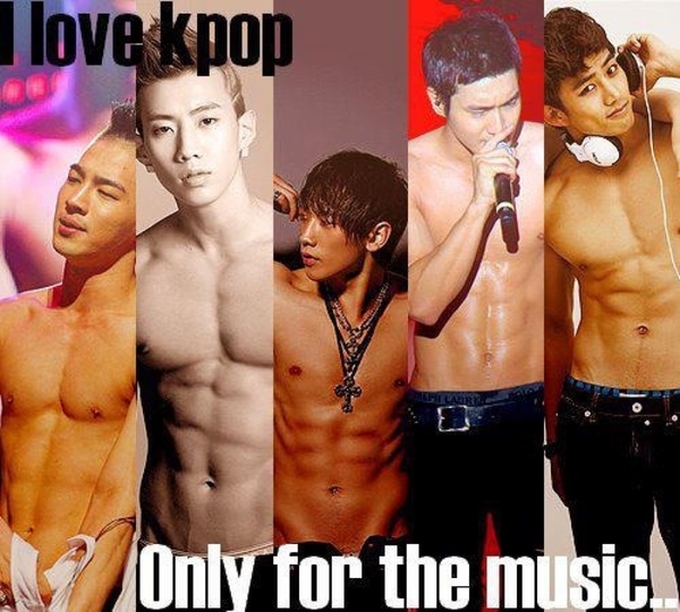

Given how family-friendly the atmosphere appears in the video of the 2019 YG Military Festival earlier, reporters raising that “fitness” performance may seem unfair, let alone my adding the compilation video in which other performers quite literally spread their legs in soldiers’ faces (I’ll let you find those scenes yourself). Similarly, in light of recent news about how important performing for the military years ago was for the sudden popularity of K-pop girl-group Brave Girls, and how devastating the loss of such opportunities due to the pandemic have been for other girl-groups, then it may seem that only a stereotypical feminist spoilsport could find any fault with that mutually-beneficial system, especially considering how tame most of the K-pop girl-groups’ performances are.

Actually, so long as universal male conscription continues, I’m not at all against performances—which is not to say there aren’t some issues that still need to be addressed with them, as examined in previous posts in this series. And yet, note that the family-friendly video is just one perspective produced by the local county government, which isn’t going to linger on the women’s bodies; unlike, say, the fancam below of New Heart, a professional cheerleading/dance team hired to perform at the 2018 festival. Also, just because this particular festival was relatively tame, that doesn’t mean something that raises more than just eyebrows may feature at the next one, let alone at more private performances on bases.

Indeed, a distinction needs to be made between performances by girl-groups and those by cheerleaders, fitness models, and so on. The former are more likely to perform in larger, more public venues; to be filmed; and to have reputations their management companies have to consider—considerations which don’t apply to private entertainers. Moreover, considering what we’ve seen of private entertainers’ performances so far, you do have to wonder what happens when no-one’s filming.

Ergo, this is no one-off. Engendering a sexually-objectified and servile view of women is fundamental to the Korean universal male conscription system. Don’t believe me? Just take the word of that military spokesperson. Not only does their feigned surprise, patronizing, disingenuous claim of ignorance, and passing of blame feel very, very familiar, but it’s surely revealing—pun intended—that their concern is over the controversy generated. Not the coercion, nor the revealing clothes.

Continuing:

군 위문공연의 선정성 문제는 국정감사에서도 제기 된 바 있다. 채이배 바른미래당 의원은 지난해 10월26일 국회 법제사법위원회 군사법원에 대한 국정감사에서군 위문공연의 문제를 지적하고 가이드라인 마련을 요구했다.

The issue of the sexual suggestiveness of morale-raising performances for the military has also been raised at the state administration. On October 26, 2018, the [since dissolved] Barunmirae Party [now former] lawmaker Chae Yi-bae pointed out the problem and demanded that guidelines be prepared during an audit of the military court of the National Assembly Legislative Judicial Committee.

채 의원은 “여성을 성상품화하는 위문공연을 폐지하라는 청와대 청원도 올라온 바 있다. 사과도 하시고 유사사례 방지하겠다고 약속하셨는데, 과연 방지할 수 있을지는 의문”이라면서 “국방부 훈령 등 지침을 살펴보니 위문공연관련 가이드라인이나 지침이 없다“고 지적했다.

Representative Chae said, “There has also been a petition from the Blue House to abolish morale-raising performances that sexually objectify women. I apologize for them and promise to work to prevent similar cases. But it is doubtful if this is possible, as there are no relevant guidelines or procedures in place.”

한편 위문공연의 성 상품화 논란이 커지자 육군은 올해 1월 외부단체 공연을 추진할 때 부대별 심의위원회를 꾸려 공연 내용을 미리 심의하겠다고 밝혔다.

However, in response to the controversy, the military announced that from January 2019 it would set up a deliberation committee for each unit to ascertain the contents of performances in advance when provided by outside companies and organizations.

If only that had extended to all companies and organizations involved, not just those providing performances. But, to finish with Money Today’s conclusions about the original incident—which may have sounded like hyperbole in isolation, whereas now:

…전문가들은 군인 사기 증진을 위해 여성을 성적 대상화하는 인식을 바꿔야 한다고 지적했다.

Experts pointed out that in order to increase military morale, the perception of sexual objectification of women should be changed.

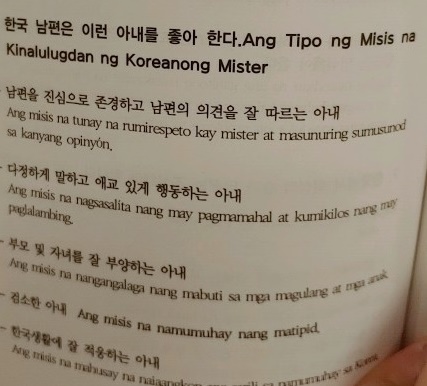

윤김지영 건국대 몸문화연구소 교수는 “여성을 눈요깃거리, 위안거리로 내세워야만 남성 군인의 사기가 증진된다고 여기는 것은 시대착오적이고 성차별적인 생각“이라며 “행사 도우미의 불편한 의상이 문제가 없다는 주장도 결국 남성주의적 관점“이라고 비판했다.

Yoon Kim Ji-young, a professor at Konkuk University’s Institute of Body & Culture, said, “It is an anachronistic and sexist idea to consider that the morale of male soldiers is enhanced only by putting women as an eye-catching and comforting object.” She criticized it as a masculine perspective.

허민숙 국회입법조사처 보건복지여성팀 입법조사관은 “군장병도 불편하고 내키지 않았을 가능성이 높다“며 “최근 젊은 남성은 여성과 동등한 관계에 익숙한 세대인데 진정한 사기 증진 방법을 고민하지 않고 낡은 관행을 답습한 점이 아쉽다“고 지적했다.

Heo Min-sook, a legislative investigator of the Health and Welfare Women’s Team at the National Assembly Legislative Investigation Department, said, “It is highly likely that military soldiers are also uncomfortable and reluctant.” I am sorry for that,” he pointed out.

Sources: left, right.

Sources: left, right.

For further reading, I highly recommend Sex Among Allies: Military Prositution in U.S.-Korea Relations (1997) by Katherine Moon and Militarized Modernity and Gendered Citizenship in South Korea (2005) by Seungsook Moon. The former, for the obvious links to the long history of girl-groups entertaining foreign and then Korean troops; and the latter, on how the gender roles and rigid hierarchy learned during military service utterly pervade Korean institutions from schools to workplaces, frequently reducing well-educated and capable women in the latter to making coffee and cleaning tables.

That doumi exist at all I’d argue, and in such great numbers, are a partial cause and effect of that last. So for the sake of completeness, in my next post, I’ll provide a full translation of an article about their origins (from 2006, I don’t think anybody will be worried about the copyright!).

Meanwhile, pondering what a Korean version of Everyday Sexism would look like is what led me to writing this post. For the sake of more like it, what other issues specific to Korea do think should be covered, which wouldn’t be in the original UK version? Please let me know in the comments!

Turning Boys Into Men? Girl-groups and the Performance of Gender for South Korean Conscripts:

- Part 6: How does military conscription affect Korean gender relations and attitudes to women?

- Part 5: South Korea’s Invisible Military Girlfriends

- Part 4: 17-Year-Old Tzuyu: “A Special Gift for Korean Men”

- Part 3: Korean Lolita Nationalism: It’s a thing, and this is how it works

- Part 2: Male Privilege at Korean Universities

- Part 1: Introduction

Related Links:

- Revealing the Korean Body Politic, Part 6: What is the REAL reason for the backlash?

- Korean Sociological Image #92: Patriotic Marketing Through Sexual Objectification, Part 1

- Korean Sociological Image #77: Sexualized Girl-Group Performances at Schools

- Woman as Consumer and the Consumed (Scribblings of the Metropolitician)

- “I Don’t Think Rights for Helpers (Doumi) Exist” (Ilda South Korean Feminist Journal)

- Policing the Student Body: Sookmyung Women’s University students told to cover up

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)

(In

(In

Screenshots from

Screenshots from